The Book of Genesis (known in Hebrew as Bereshit) begins with the creation of the world by God, from tohu v’bohu, chaos and nothingness. God calls for light, separates the darkness from the light creating day and night, creates the “great waters,” separates land from sea, and eventually fills the earth with creatures—fowl, fish, land animals, and finally man and woman. In fact, Bereshit tells the story of the creation twice, with significant differences between the two versions.

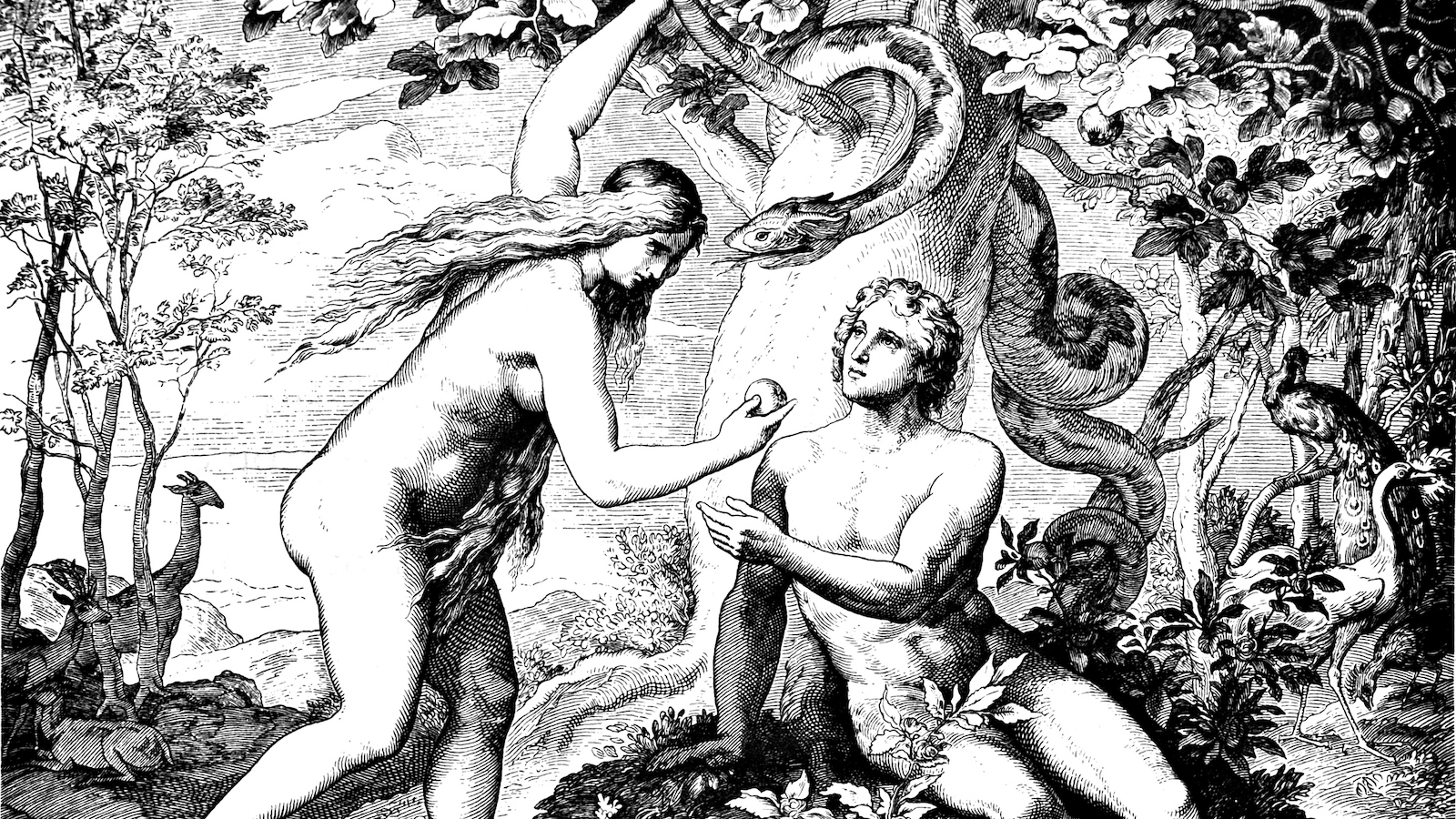

Adam and Eve

Almost immediately after the creation of humans, problems begin. Eve is tempted by the serpent and violates God’s explicit orders, eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and encouraging Adam to do likewise. They are expelled from the Garden of Eden. Eve bears children, Cain and Abel, and eventually Cain kills his brother and is condemned to wander the earth.

Noah

After several more generations, God decides that humanity was a bad idea and resolves to obliterate man and woman from the face of the earth, save for Noah and his family. Noah and his kin are saved and with them is an assortment of the animals as well. Eventually, after the floodwaters have subsided, Noah will offer a sacrifice to God, who promises never to repeat this mass extermination. However, it is not long before humans again test God’s patience, building the Tower of Babel. The Almighty responds this time by scattering them across the face of the earth and confounding their language; they will now speak in many tongues and be unintelligible to one another.

The Patriarchs and Matriarchs

All of this is but a lengthy prelude to the main story of Bereshit, the story of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs who founded the Hebrew people: Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob, Leah, and Rachel, Joseph and his brothers. Each of these stories pivots on a covenant between the Creator and the Patriarch of his generation, each involves wandering and exile ending in redemption and, finally, a gentle but poignant death. In at least two key cases, central figures are given new names by God, indicating the transformation that their covenant requires.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

God’s first words to Abram (his name when we first meet him) are “Lech lecha (Go forth).” Thus the first of the Patriarchs is sent out into a hostile world with the message that there is only one Deity. God gives an aging Abram and Sarai a son, a token of the promise to make Abram’s seed as numerous as the stars in the sky. Yet neither as Abram nor as Abraham is the Patriarch a docile servant of the Almighty. Rather, when God resolves to destroy the cities on the plain, Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham argues unbendingly for their salvation and, only after he is unable to find even ten righteous men and women within them does he wearily accede to God’s decision.

Abraham/Abram is not presented as a perfect man. None of the Patriarchs is. His behavior in the matter of his concubine Hagar and her son by him, Ishmael, whom he sends into the desert at Sarah’s behest, is clearly wrong. If it were not, why would the messenger of God save Hagar and Ishmael when they are dying of thirst in the wilderness, an unstated but clear rebuke to Abraham’s expulsion other?

And, in light of his resistance to the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham seems all too willing to follow orders and sacrifice Isaac, his son, on Mount Moriah. And yet …the storv of the akedah (the binding) of Isaac is a good example of how complicated the undercurrents and outcome of biblical narrative can be, of why it is dangerous to jump to seemingly obvious conclusions based on a contemporary understanding of an ancient text.

Perhaps Abraham trusts in God, trusts that the Almighty will not let his son die. God has promised to make Abraham’s descendants a great nation; Abraham must believe in the covenant and surely God will not take Isaac. If this is to be a test of faith, then the test goes both ways. God tests Abraham’s willingness to follow a divine commandment to the very brink. Abraham tests God’s willingness to avert further shedding of human blood—this time innocent blood—and to keep the covenant.

Isaac is the least defined, the most passive of the Patriarchs. In his key moments in Bereshit—the Akedah and Jacob’s deception leading to his receiving the blessing meant for his older brother—he is acted upon, not active. Alone among the Patriarchs, Isaac doesn’t even choose his own wife; his father’s servant does it for him. We know more about Rebekah, his wife, her desire for children, the pain of her childbirth, her favoring of the younger of her twin sons, Jacob, over the elder, Esau. Isaac seems to exist primarily to be deceived by Jacob into giving over the blessing owed the firstborn.

Two nations struggle to be born in Rebecca’s womb, Israel and Edom, represented by her sons Jacob and Esau, respectively. Eventually the bookish younger son Jacob, “a man of the tents” will supplant his older brother Esau, “a man of the fields,” by bargaining for the latter’s birthright and taking advantage of their aged father’s failing eyesight to secure the blessing intended for the firstborn. Then, afraid of his older brother’s understandable wrath, Jacob will go to Beersheva. In Beersheva, Jacob will meet and fall in love with Rachel. He will labor for seven years for his prospective father-in-law Laban, only to be tricked into marrying her older sister, Leah. After another seven years’ labor for Laban, he will finally marry the younger sister as well. On the road [back to Canaan], he encounters and wrestles with a mysterious being who turns out to be a messenger of God. As the morning light begins to glimmer on the horizon, the messenger defeats him by dislocating his hip, then rewards him with a new name, Israel, and a restatement of the covenant that God had made with his grandfather.

The ethics of Jacob’s behavior toward his father and brother are troubling to modern sensibilities, to put it mildly. To our eyes, it looks like Jacob has in essence perpetrated a fraud upon his own father to secure a blessing not rightly his, and held his brother to an absurd bargain to obtain a birthright he doesn’t deserve. The sages of the rabbinic period had no such problems. To them, Jacob was clearly the son favored by God, the one who studied Torah (although it hadn’t been written yet!), the one whose line would become the Israelite people. There are numerous midrashic texts that describe Esau variously as an isolator and killer, one who disdained his birthright and the responsibilities of the covenant.

Such ex post facto explanations do not satisfy modern readers; they smack of special pleading. But there is another fact to consider. Jacob suffers the most of any of the Patriarchs for his legacy. If he purchases the birthright cheaply and the blessing illicitly, he pays for them soon after with the coin of physical pain, fear for his life, some fifteen years as a fugitive, indentured servitude, a shattered family, and death in exile. It is worth noting that, as Professor Joel Rosenberg points out, punishment from God in the Torah almost never comes immediately after the transgression (with the notable exceptions, I would add, of Adam and Eve in the Garden and Lot’s wife); rather, it may befall the malefactor much later, perhaps even in a later generation.

Joseph and His Brothers

The story of the disruption of Jacob’s family, the tale of Joseph and his brothers, is the most extended narrative in the book of Genesis, being told over four sidrot (weekly portions). Joseph has a knack for interpreting dreams, his own and those of others, a skill that gets him in trouble with his brothers but gets him out of Pharaoh’s prison in Egypt.

The root of Joseph’s conflict with his brothers lies in his status as Jacob’s favorite son. (Given the troubles that he went through with his own brother and parents, one would think Jacob would know better, but this is a recurring theme throughout the Torah.) His brothers fake his death and sell him to a passing slave caravan. He ends up in Egvpt where, after a series of misadventures, his mastery of dream interpretation raises him to the status of the Pharaoh’s principle advisor. His ingenuity in the face of a lengthy famine helps Pharaoh consolidate his hold over Egypt, and indirectly brings him face to face with his brothers once more. After tormenting them with accusations of theft (with planted evidence to back him up), he finally reveals himself to them, they bring the aged Jacob to Egypt reuniting the family, and they all live happily ever after in Egypt, more or less.

Or at least until a new Pharaoh arises “who knew not Joseph.” But that is the story of the next four books.

Reprinted with permission from Essential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs, and Rituals, published by Pocket Books.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.