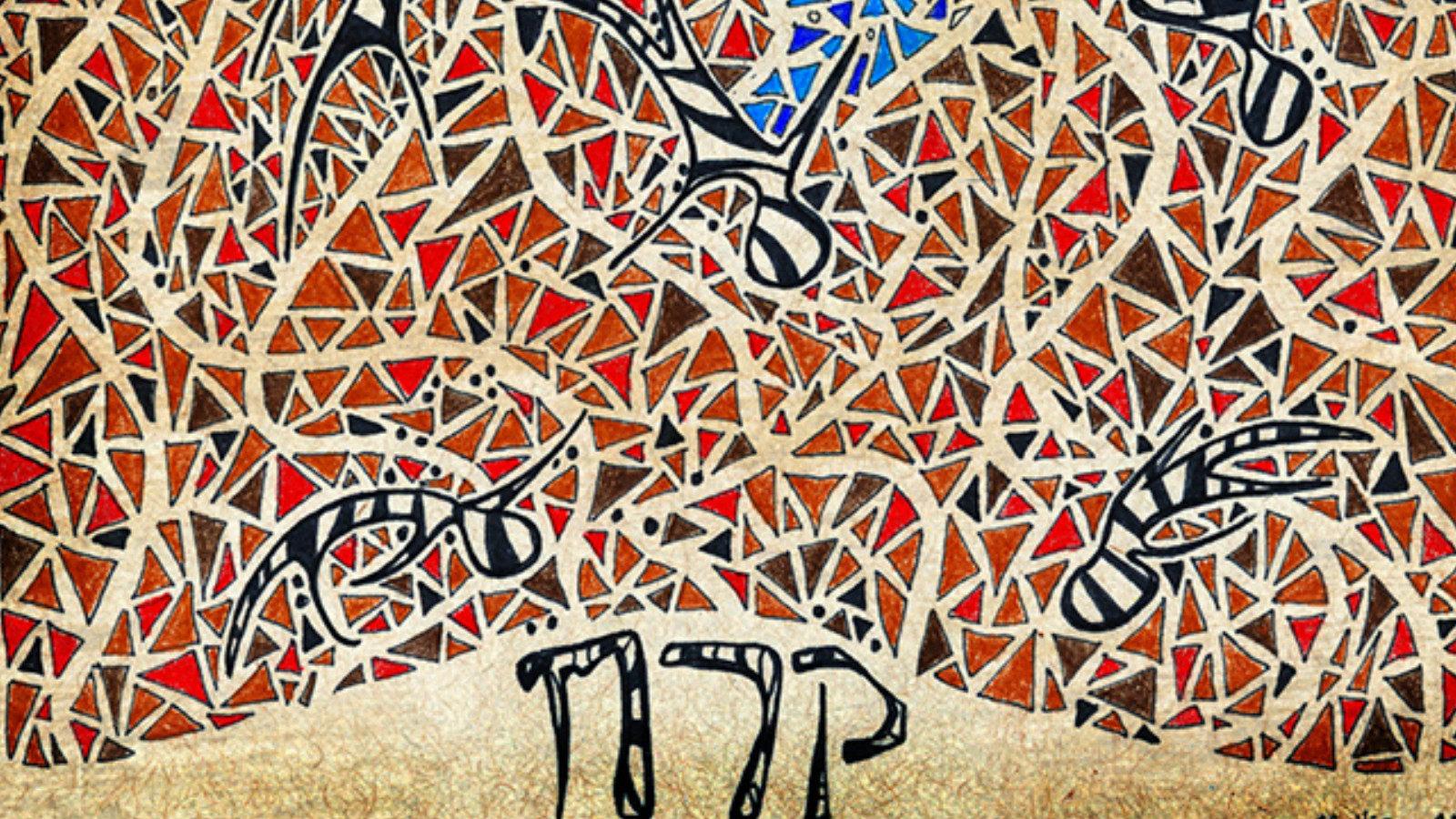

Commentary on Parashat Korach, Numbers 16:1-18:32

Parashat Korach is a chaotic mess. Within the 95 verses of this Torah portion are multiple active rebellions accompanied by multiple acts of divine punishment, all intertwined in a confusing and complicated narrative. But within this jumble lies a deep lesson about how to bring order to chaos and emerge from challenging times.

At the heart of this portion are attempts by multiple members of the Israelite community to gain power. First, the eponymous Korach and his followers seek religious and communal power, addressing Aaron and Moses saying: “You have gone too far! For all the community are holy, all of them, and the LORD is in their midst. Why then do you raise yourselves above the LORD’s congregation?” Later, two other community members, Datan and Aviram, address their complaint to Moses specifically, seeming to suggest their insurrection was only against the power he personally wielded.

Rather than a straightforward story, the narrative of these critiques keeps changing. Sometimes Datan and Aviram are mentioned as being with Korach, sometimes they appear separately. Key details, such as whether Korach was consumed by divine fire or swallowed alive by the earth, are the subject of later debate. The narrative confusion helps to align the reader to the disorientation Moses must have felt when his leadership was attacked by multiple detractors. It also makes the chaos of the wandering in the desert vivid to modern readers.

At the climax of the rebellion, Korach and his followers are instructed to offer incense in their fire pans alongside Aaron, a test to see whom God favors. When the rebels offer their incense, they are consumed as punishment by a divine fire. In the aftermath of this, God makes what appears to be an odd demand, instructing the Israelites to make the pans into sheets as plating for the altar. Commentators have struggled to understand how the pans could have become consecrated and used to beautify the altar after they had been used in an attempt to usurp power from Moses and Aaron.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Nechama Leibowitz, drawing on the medieval commentator Ramban, writes in response to this difficulty, “The holiness of the vessels did not originate in the actions of those who sinned, but God had them sanctified to serve as a lesson to the people.” That is, it was God — not Korach and his followers — who transformed the fire pans into vessels suitable for divine service. The plating of the altar with the pans then represents the return of ritual order, and the ending of the chaos sown by Korach and his supporters.

It is striking to consider that physical objects once used to sow chaos and dissent can be elevated into objects of beauty and holiness. Even more striking is that the pans forever changed the appearance of the altar. As God commanded, no Israelite could again look at the altar again without being reminded of Korach and his fate.

What the transformation of the fire pans tells us is that order can always be restored from chaos, but it will require transformation. And like the altar, that restored order will look very different than what came before.