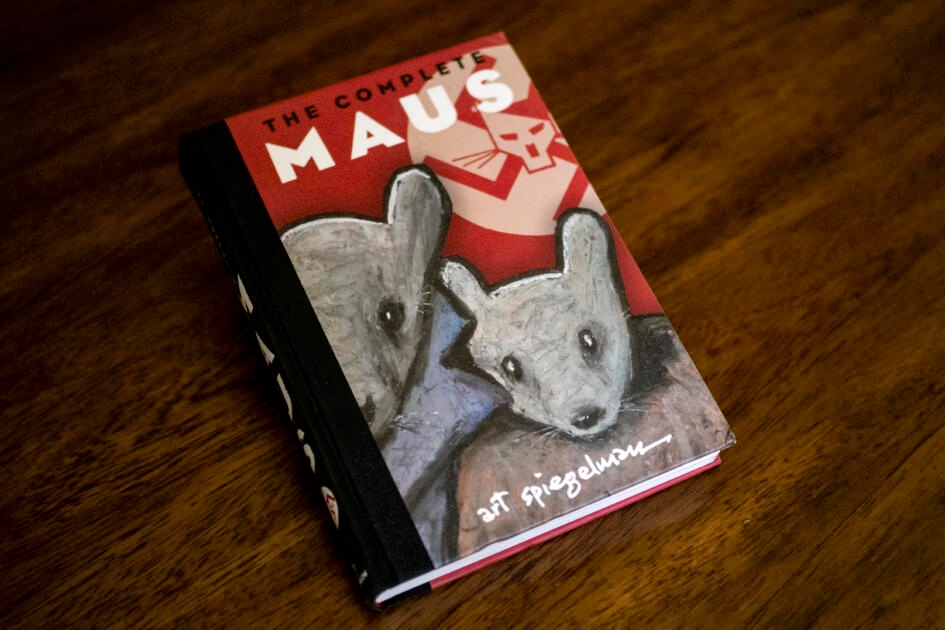

From cartoonist to chronicler of the Holocaust, Art Spiegelman’s career has followed an unlikely journey deeper into himself, and into history. Spiegelman, in his own way, is an innovator, having played a part in the creation of a new literary subgenre with his graphic novel Maus (1986).

Spiegelman was born in 1948 in Stockholm to Holocaust-survivor parents, and was raised in the New York neighborhood of RegoPark. He began drawing comics for underground publications devoted to more provocative and youth-culture topics (think sex and drugs) than the genial Sunday cartoons. Spiegelman founded RAW magazine with his wife Francoise Mouly in 1980. The magazine featured work by classic cartoonists like George Herriman and Winsor McCay, alongside new material by graphic novelists like Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware. It was also where Spiegelman first published the stories that would later become Maus.

Maus borrowed from the tradition of the comics and graphic novels Spiegelman had been raised with, like George Herriman’s visually lush, occasionally surrealist tale of a cat, a mouse, and a dog in Krazy Kat. As far as the narrative, Spiegelman had a complicated relationship with his father, Vladek, and this inspired the younger Spiegelman to explore the story of Vladek’s Holocaust experience.

As the title suggests, in Maus, Spiegelman drew Jews as mice. Nazis as cats, and Poles as pigs. Spiegelman teetered deliberately on the edge of stereotype, toying with the image of Jews as helpless victims, the playthings of their bigger, fiercer antagonists. But Maus invests the stereotypes with deep feeling, and the inherent cruelty of Jewish victimhood is placed under the microscope. “If Maus is about anything,” Spiegelman told interviewer Lawrence Weschler, “it’s a critique of the limitations—the sometimes fatal limitations—of the caricaturizing impulse.”

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

While the form of Maus reflects old comic strips like Krazy Kat and the works of R. Crumb, the inspiration was more personal, more freighted with the weight of history and family. In the book’s framing story, Art visits his father to record his story and is waylaid by the everyday frustrations of his relationship with his father. In one of Maus’ most memorable scenes of domestic disharmony, Vladek tosses out Art’s coat when he comes to visit. Later, he invites Art over to have him fix his leaky drain pipe. Once they settle down, though, Vladek escorts his son through the memories of his past: the Nazi invasion of Poland, his time in a POW camp, the death of his son Richieu, surviving Auschwitz alongside his wife.

Maus is not just Spiegelman’s father’s story; it toggles between past and present, offering snatches of Vladek’s saga amongst instances of Art’s struggle with his difficult father, and the author’s struggle with the complexity of how to tell the story of the Holocaust. His father is no storybook hero, and neither is he. “You! You murderer! How the hell could you do such a thing!” Art shrieks when Vladek tells him he had destroyed his mother’s notebooks.

His father is a survivor, in every sense of the word, but so is Art, who endures the brunt of his father’s painful memories. “Friends? Your friends?” Vladek blusters to Art during his 1950s childhood, as his son blubbers about being left behind by his schoolmates. “If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week…THEN you could see what it is, friends!” The genius of Maus is that it values Art’s story no less than Vladek’s.

The first volume of Spiegelman’s opus was published in 1986, with the second following in 1991. Maus emerged as the form it helped to create—the graphic novel—was coming to maturity, moving beyond its babes-and-adventure adolescence toward darker, more serious subjects. Maus won the Pulitzer Prize—the first, and still the only, graphic novel to ever win the award. Like Elie Wiesel’s Night and Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz, Maus renders the enormity of the Holocaust in personal terms. It also retains a certain ambiguity at its heart that allows readers to keep revisiting it, keep pondering its questions.

Some critics were ill-disposed to the depiction of Jews as mice, with its implication of helplessness, but most saw Maus as a groundbreaking work of art. “Maus is a masterpiece, and it’s in the nature of such things to generate mysteries, and pose more questions than they answer,” says novelist Phlip Pullman. “But if the notion of a canon means anything, Maus is there at the heart of it. Like all great stories, it tells us more about ourselves than we could ever suspect.”