Born in Philadelphia in 1798, Warder Cresson was raised a Quaker. He became a wealthy farmer in rural Pennsylvania, married and had a son. He also became a lifelong seeker of religious truth. By the 1840s, Cresson had become, in turn, a Shaker, a Mormon, a Seventh-day Adventist, and a Campbellite. The latter two denominations believed that the Second Coming of Christ was close at hand. Cresson became notorious in Philadelphia for religious “haranguing in the streets,” warning all within earshot of the approaching apocalypse.

In 1844, Cresson expressed his certainty that God was about to gather the Jewish people in Jerusalem as a prelude to the “end of days.” Cresson wrote, “God must choose some medium to manifest and act through, in order to bring about his designs and promises in this visible world; This medium or recipient is the present poor, despised, outcast Jew God is about gathering them again [in Jerusalem].” Cresson decided to move to Jerusalem to witness the great event. His family stayed behind.

Before departing, Cresson volunteered to work as the first American consul in Jerusalem, which was then a part of Syria. His Pennsylvania congressman, Edward Joy Morris, lobbied the State Department to have him appointed. Soon after Cresson sailed, however, a former cabinet official informed John C. Calhoun, then Secretary of State, that Cresson was mentally unstable. Calhoun dispatched a letter to Cresson, which reached him in Jerusalem, informing him that his appointment had been rescinded.

Cresson decided to stay on in Jerusalem despite this disappointment. He had come as an evangelical Christian to witness God’s ingathering of the Jewish Diaspora. His time in Jerusalem, however, drew him to become a Jew. The impoverished, deeply religious Jews he found in Jerusalem, who were living with only the barest necessities, touched Cresson’s heart. Cresson was offended by the “soul snatching” behavior of Christian missionaries who attempted to bribe some Jews with food and clothing into accepting conversion. He wrote, “The conversions which have been reported . . . [by] the Protestant Episcopal Mission were owing to the wants of the converts, not to their conviction.” He expressed admiration for those Jews who resisted conversion despite the material incentives.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

As historian Abraham J. Karp notes, “By 1847 Cresson already felt himself more a Jew than Christian.” In March 1848, Cresson took the plunge and converted. “I became fully satisfied,” he wrote, “that I could never obtain Strength and Rest but by doing as Ruth did, and saying to her Mother-in-Law: thy People shall be my people, and thy God my God I was circumcised, entered the Holy Covenant, and became a Jew.”

To close his affairs in America, Cresson returned to Philadelphia, where he was greeted by trouble. “Soon after my return,” Cresson wrote, “I found that there was a growing OPPOSITION and ENMITY toward the course I had taken.” Cresson’s wife and son started a civil “Inquisition of Lunacy” to have Cresson declared insane for choosing Judaism. The jury declared Cresson a lunatic. In 1850, Cresson appealed the verdict and received a new trial. The press gave it sensational coverage. More than 100 witnesses testified. The jury ultimately found for Cresson. An editorial in the Philadelphia Public Ledger hailed the verdict “as settling forever the principle that a man’s religious opinions never can be made the test of his sanity.”

During the four years Cresson spent in Philadelphia waiting for his trial to end, he worshipped at Congregation Mikveh Israel, lived according to halachah and participated in Jewish communal life. At some point, he divorced. He also took a new name: Michael Boaz Israel. In 1852, Cresson/Israel sailed for Jerusalem, this time as a Jew. He brought with him a self-published plan “for the Promotion of Agricultural Pursuits [and] for the Establishment of a Soup-House for the Destitute Jews in Jerusalem.” Cresson’s desire for a soup house was to “prevent any attempts being made to take advantage of the necessities of our poor brethren” that would “FORCE them into a pretended conversion.”

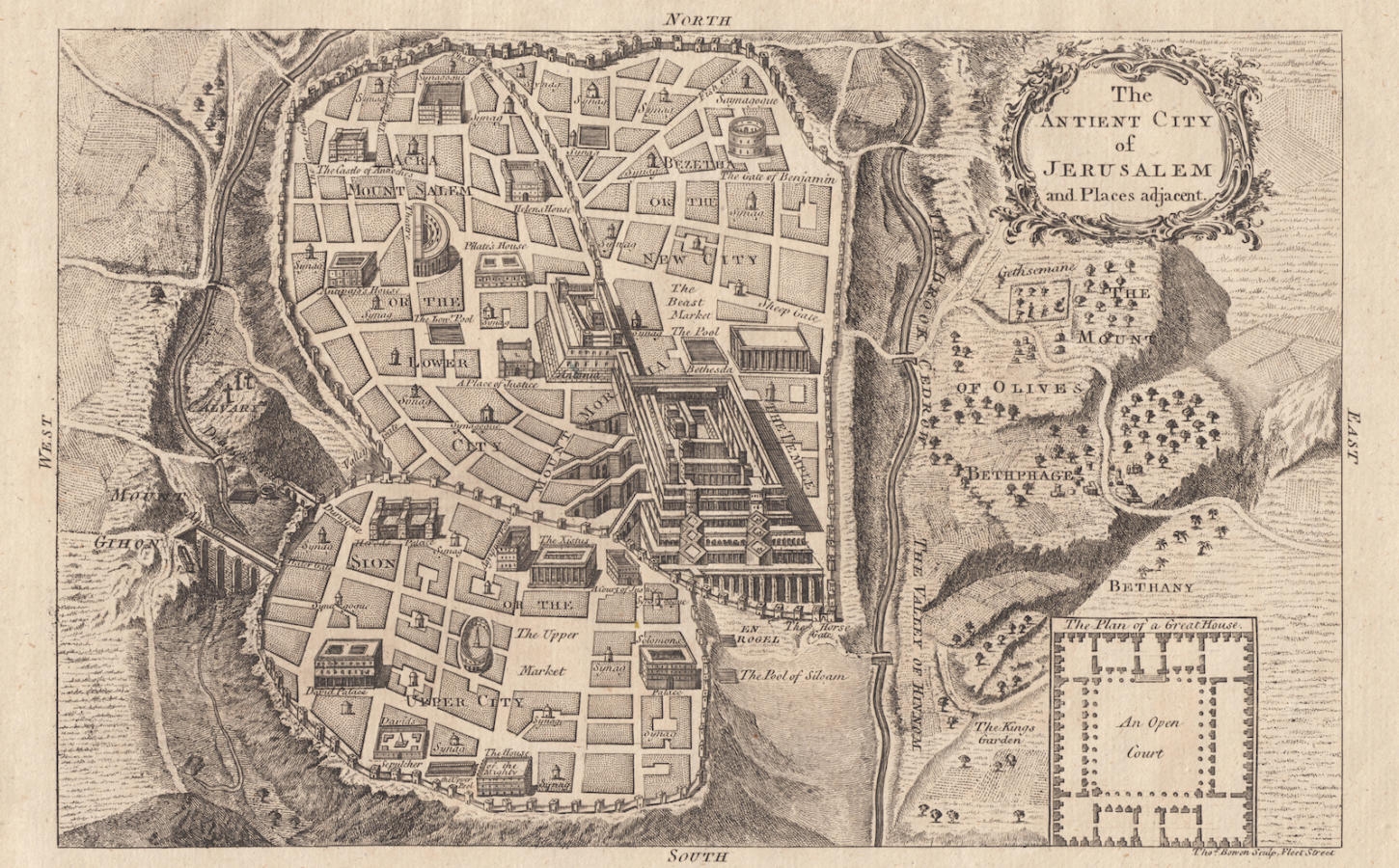

His vision for agricultural development was far reaching, anticipating later Zionist principles. Cresson called for “the Restoration and Consolidation of all Israel to their own land because Unity and Consolidation is Strength.” This strength would come from agriculture, providing the ingathered Jewish people with sustenance denied it for hundreds of years. To prove his plan could work, Cresson announced that he was starting a model farm in the Valley of Rephaim, outside Jerusalem, “to introduce an improved system of English and American Farming in Palestine.” He hoped that a Jewish agricultural Palestine “a great center to which all who rest may come and find rest to their persecuted souls.”

Cresson’s planned model farm never developed for want of capital, but he continued to pray for its success. In the mid-1850s, he married Rachel Moleano and became an honored member of Jerusalem’s Sephardic community. When he died in 1860, he was buried on the Mount of Olives “with such honors as are paid only to a prominent rabbi.” After a long journey, Warder Cresson found his spiritual home in Jerusalem as Michael Boaz Israel.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.

Sephardic

Pronounced: seh-FAR-dik, Origin: Hebrew, describing Jews descending from the Jews of Spain.