There is one custom which we would expect to find on Hanukkah that is missing–the reading of a scroll in public. After all, on Purim we read the Scroll of Esther every year in order to publicize the miracle. Why don’t we read a scroll on Hanukkah in order to publicize the miracles which God wrought for our ancestors in the days of Matityahu [the priest central to the Hanukkah story] and his sons [the Maccabees]?

The result is that most Jews only know the legend about the miracle of the cruse of oil (Shabbat 21b) and not about the actual military victories of the Maccabees.

The Scroll

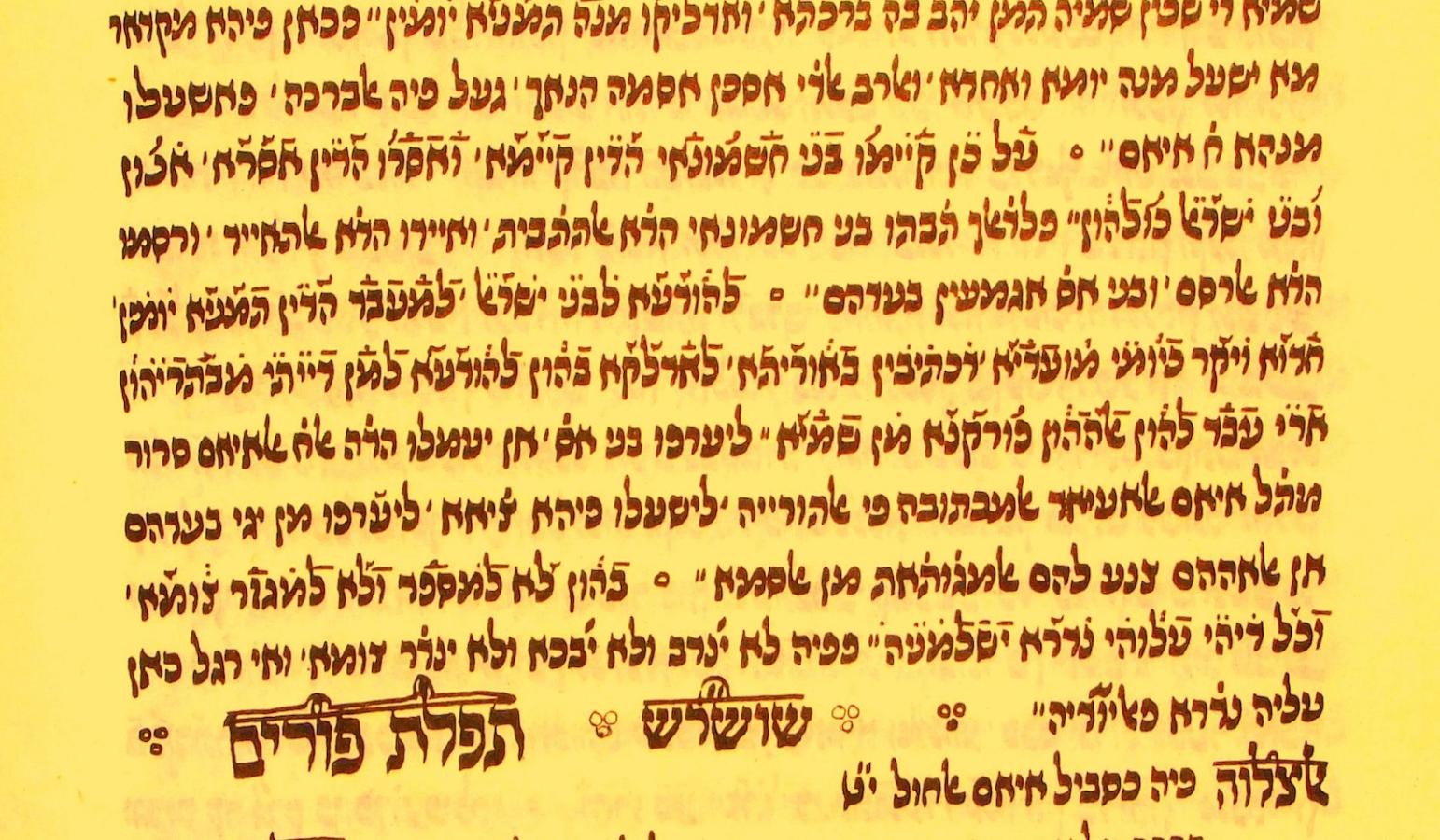

The answer is that, in truth, there is such a scroll that was read in private or in public between the ninth and 20th centuries. It is called “The Scroll of Antiochus” and many other names, and it was written in Aramaic during the Talmudic period and subsequently translated into Hebrew, Arabic, and other languages. The book describes the Maccabean victories on the basis of a few stories from the Books of the Maccabees and Shabbat 21b, with the addition of a number of legends without any historic basis whatsoever.

The scroll is first mentioned by Halakhot Gedolot, which was written by Shimon Kayara in Babylon ca. 825 C.E.: “The elders of Bet Shammai and Bet Hillel wrote Megillat Bet Hashmonay [the scroll of the Hasmonean House]…” Rav Sa’adia Gaon (882-942) calls it “kitab benei hashmonay,” the book of the sons of the Hasmoneans, and he also translated it into Arabic. Rav Nissim Gaon (North Africa, 990-1062) calls it in Arabic “the scroll of the sons of the Hasmoneans.”

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Furthermore, we know that this scroll was read in public at different times and places. Rabbi Isaiah of Trani (Italy, ca. 1200-1260) says that “in a place where they are accustomed to read Megillat Antiochus [The Scroll of Antiochus] on Hanukkah, it is not proper to recite the blessings [for reading a scroll] because it is not required at all.”

Varying Customs

In Mahzor Kaffa, which was published in the Crimea in 1735, the Scroll of Antiochus is printed in Hebrew and preceded by the following instructions:

It is customary to read Megillat Antiochus during Mincha [the afternoon service on Shabbat] after Kaddish Titkabbel [the Reader’s Kaddish] in order to publicize the miracle [of Hanukkah]…

Rabbi Yahya ben Yosef Zalih, who was the leading rabbi in San’a, Yemen, ca. 1715, says “that some read Megillat Antiochus on Shabbat [of Hanukkah] after the haftarah [reading from the Prophets]. This is not required; it is only a general mitzvah to publicize the miracle among the Jewish people.”

But Rabbi Amram Zabban of G’ardaya in the Sahara Desert viewed this reading as a requirement. In his Sefer Hasdey Avot, published in 1926, he states:

Megillat Antiochus according to the custom of the holy city of G’ardaya, may God protect her. The cantor should read it in public in the synagogue after the Torah reading on the Shabbat during Hanukkah. And he reads it in Arabic translation so that the entire congregation should understand [in order to] publicize the miracle which was done to our holy ancestors, may their merit protect us…translated from the Hebrew from Siddur Bet Oved of R. Yehudah Shmuel Ashkenazi [Livorno, 1853].

This is a fascinating passage. Rabbi Zabban translated Megillat Antiouchus from Hebrew into Arabic in 1926 so that the entire congregation would understand it. He seems unaware that Arabic translations already existed. He also presents this custom as a required activity, despite the fact that he seems to have made it up! Perhaps he had heard that this was an accepted custom in other communities and wished to imitate them.

The Jews of Kurdistan, on the other hand, used to read the Scroll of Antiochus at home during Hanukkah. Rabbi Yosef Kafah (1917-2000) reports that his grandfather Rabbi Yihye Kafah (1850-1932) used to teach it to his pupils in Yemen in the Aramaic original along with the Arabic translation of Rav Sa’adya Gaon.

A Scroll for Today

It would seem that there is no point in reviving the specific custom of reading the Scroll of Antiochus in public, because that work is legendary in nature and not a reliable source for the events of Hanukkah. But we do possess such a source for those events–the First Book of Maccabees, which was written in Hebrew in the Land of Israel by an eyewitness to the events described therein.

Therefore, we should thank Rabbi Arthur Chiel who published the First Book of Maccabees, Chapters 1-4, as a separate booklet over 20 years ago under the title “The Scroll of Hanukkah.” It is intended for reading in public or in private during the holiday. We should adopt this beautiful custom and begin to read those chapters in public every year on the Shabbat of Hanukkah after the Haftarah. By so doing, we will be reviving the custom of reading a “scroll” on Hanukkah but, more importantly, we will thereby disseminate the oldest surviving account of the “miracles and triumphs” which God performed for the Jewish People “in those days at this season.”

Excerpted with permission from the website of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies.

Explore Hanukkah’s history, global traditions, food and more with My Jewish Learning’s “All About Hanukkah” email series. Sign up to take a journey through Hanukkah and go deeper into the Festival of Lights.

Ashkenazi

Pronounced: AHSH-ken-AH-zee, Origin: Hebrew, Jews of Central and Eastern European origin.

Hanukkah

Pronounced: KHAH-nuh-kah, also ha-new-KAH, an eight-day festival commemorating the Maccabees' victory over the Greeks and subsequent rededication of the temple. Falls in the Hebrew month of Kislev, which usually corresponds with December.

Mahzor

Pronounced: MAKH-zore, Origin: Hebrew, literally “cycle” the mahzor is the special prayer book for the High Holidays, containing all the liturgy for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

megillah

Pronounced: muh-GILL-uh, Origin: Hebrew, meaning "scroll," it is usually used to refer to the scroll of Esther (Megillat Esther, also known as the Book of Esther), a book of the Bible traditionally read twice during the holiday of Purim. Slang: a long and tedious story or explanation.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Purim

Pronounced: PUR-im, the Feast of Lots, Origin: Hebrew, a joyous holiday that recounts the saving of the Jews from a threatened massacre during the Persian period.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Haftarah

Pronounced: hahf-TOErah or hahf-TOE-ruh, Origin: Hebrew, a selection from one of the biblical books of the Prophets that is read in synagogue immediately following the Torah reading.