Commentary on Parashat Chayei Sara, Genesis 23:1-25:18

- Abraham purchases the cave of Machpelah in order to bury his wife Sarah. (23:1-20)

- Abraham sends his servant to find a bride for Isaac. (24:1-9)

- Rebecca shows her kindness by offering to draw water for the servant’s camels at the well. (24:15-20)

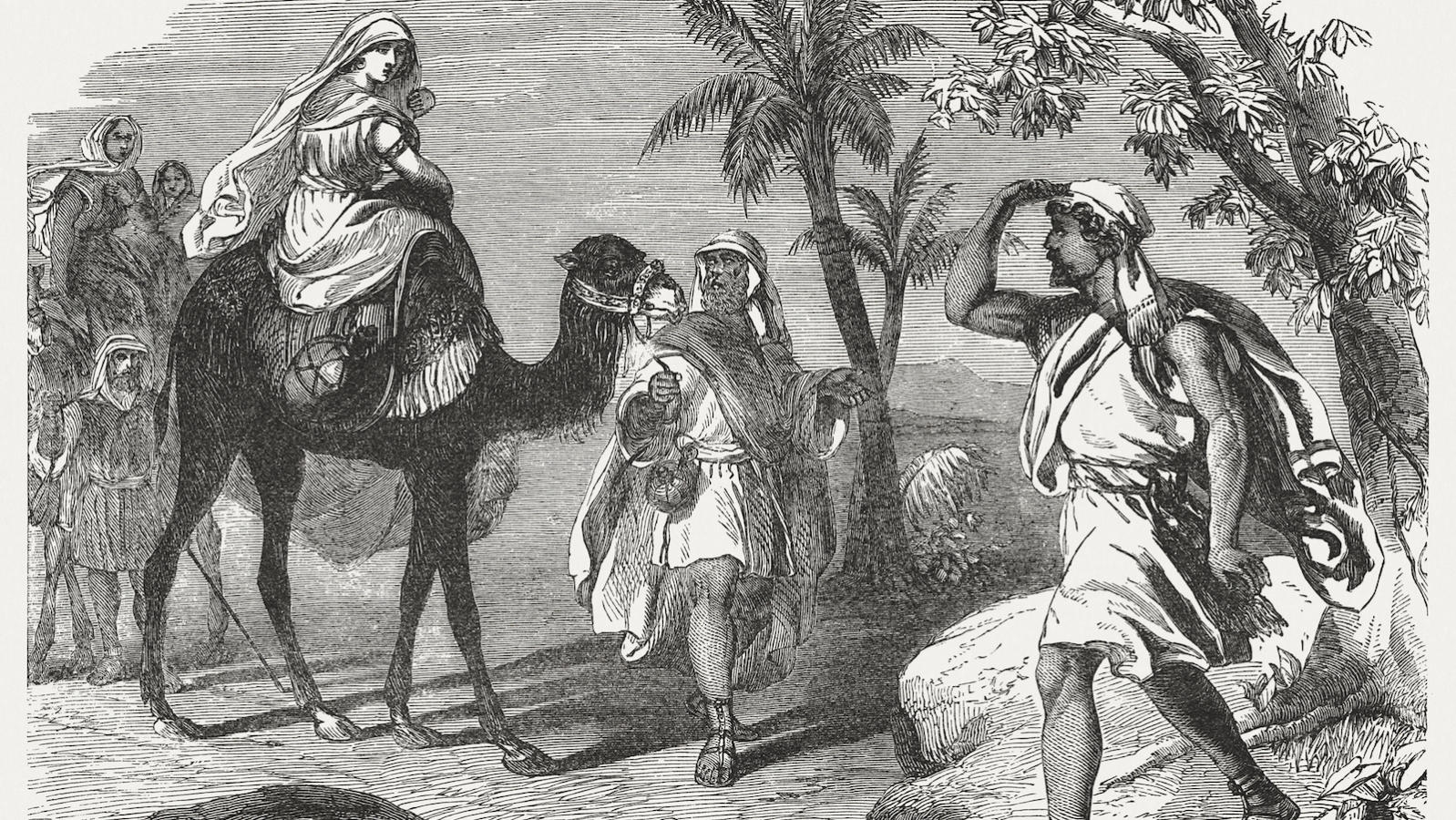

- The servant meets Rebecca’s family and then takes Rebecca to Isaac, who marries her. (24:23-67)

- Abraham takes another wife, named Keturah. At the age of one hundred and seventy-five years, Abraham dies, and Isaac and Ishmael bury him in the cave of Machpelah. (25:1-11)

Focal Point

Isaac had just come back from the vicinity of Beer-lahai-roi, for he was settled in the region of the Negev. And Isaac went out walking in the field toward evening and, looking up, he saw camels approaching. Raising her eyes, Rebecca saw Isaac. She alighted from the camel and said to the servant, “Who is that man walking in the field toward us?” And the servant said, “That is my master.” So she took her veil and covered herself. The servant told Isaac all the things that he had done. Isaac then brought her to the tent of his mother, Sarah, and he took Rebecca as his wife. Isaac loved her, and thus found comfort after his mother’s death (Genesis 24:62-67).

Your Guide

After Abraham’s death, Isaac settled in Beer-lahai-roi (Genesis 24:62). This was also the place in which Hagar encountered an angel when she first fled from Sarah (Genesis 16). Is there a possible hidden significance of this place for Isaac?

When they meet, Rebecca and Isaac both exchange words with the servant but say nothing to each other. Why?

Prior to their meeting, the text says about both Isaac and Rebecca that “she/he raised up her/his eyes.” Does this phrase suggest just a physical raising of the eyes or an inner emotional shift as well?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Isaac’s dead mother, Sarah, is mentioned twice in verse 67. Is Isaac’s awareness of his mother’s presence excessive, or is it to be expected at the time of his marriage?

By the Way…

“From the vicinity of Beer-lahai-roi.” He had gone there to take Hagar to his father Abraham, for him to marry her (Rashi on Genesis 24:62). [Note: According to midrashic tradition, Abraham’s new wife, Keturah, was actually Hagar.]

“From the vicinity of Beer-lahai-roi.” To pray in that place, in which was heard the prayer of the slave woman [Hagar]. And even before he prayed, the matter had already been concluded in Haran, and his wife was on her way to him. As it says, “Before they call out, I respond” (Isaiah 65:24). He left the road to pour out his prayer to God in a field so that passersby would not interrupt (Sforno on Genesis 24:62).

“To the tent of his mother, Sarah.” He brought her [Rebecca] to the tent and, behold, she was Sarah, his mother! That is to say, she followed Sarah’s example. For as long as Sarah lived, a candle burned from erev Shabbat to erev Shabbat, and there was a blessing in the challah dough, and a cloud was attached to the tent. When she died, all these things disappeared. And when Rebecca came, they returned (Rashi on Genesis 24:67).

“After his mother’s death.” The way of the world is that as long as a man’s mother is alive, he is bound up with her. And when she dies, he is comforted by his wife (Rashi on Genesis 24:67).

Rabbi Jose says: For three years, Isaac mourned for his mother, Sarah. After three years, he took Rebecca and forgot the mourning for his mother. From this you learn that until a man takes a wife, his love follows his parents. When he takes a wife, his love follows his wife, as it is said, “Therefore does a man leave his father and his mother and clings to his wife” (Genesis 2:24). But does a man depart from the mitzvah (commandment) of honoring his mother and father? Rather, his love clings to his wife (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 32).

“Rebecca saw Isaac.” She saw him majestic, and she was dumbfounded (Rashi on Genesis 24:64).

What Rebecca sees in Isaac is the vital anguish at the heart of his prayers, a remoteness from the sunlit world of chesed (kindness) that she inhabits. Too abruptly, perhaps, she receives the shock of his world. Nothing mediates, nothing explains him to her. “Who is that man walking in the field toward us?” (Genesis 24:66) she asks, fascinated, alienated. What dialogue is possible between two who have met in such a way?

A fatal seepage of doubt and dread affects her, so that she can no longer meet him in the full energy of her difference. She veils herself, obscures her light. He takes her and she irradiates the darkness of his mother’s tent. She is, and is not, like his mother; through her, his sense of his mother’s existence is healed. But the originating moment of their union is choreographed so that full dialogue will be impossible between them (Aviva Gottlieb Zornberg, Genesis, The Beginning of Desire, pp. 142-143).

Your Guide

It is poignant to imagine the relationship between Isaac and Hagar, the woman who had been banished by his own mother. How does Sforno’s view of Isaac’s connection to Hagar compare with Rashi’s view of their relationship?

Rashi, commenting on Genesis 24:67, cites the death of a man’s mother as the turning point in his emotional life. Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer identifies it as the moment of a man’s marriage. Which view resonates with your own experience?

Zornberg considers the meeting and marriage of Isaac and Rebecca as profoundly troubled from the start. Do you agree?

D’var Torah

In the Jewish tradition, we take the marriage of Isaac and Rebecca as our paradigm. From this wedding come our customs of the veil, the blessing of the bride, and the halakhah (Jewish law) that a woman must be asked if she consents to the marriage. In the Torah text itself, the elements of the field, the setting sun, Isaac’s prayer (the mysterious verb lasu-ach), and the train of camels create a romantic, mystical mood. Our Sages and medieval commentators looked beyond the surface of the text to read the more complex emotions inherent in this first meeting between a man and woman who would become husband and wife and to explore the complicated history that each of these individuals brought to that encounter.

Provided by the Union of Reform Judaism, the central body of Reform Judaism in North America.

challah

Pronounced: KHAH-luh, Origin: Hebrew, ceremonial bread eaten on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

erev

Pronounced: EH-ruv, Origin: Hebrew, evening, eve, usually used to denote the first night of a Jewish holiday, such as Erev Yom Kippur (Jewish days begin at sundown).

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.