Commentary on Parashat Ha'Azinu, Deuteronomy 32:1-52

This week’s portion, which nearly completes the annual reading of the entire Torah, reflects on the past as it simultaneously offers a powerful vision for the future. As a result, the subtlety of this portion and the myth that has been perpetuated through its common retelling yearns for further exploration.

Moses will not be allowed into the Promised Land. The primary reason offered is his disobedience: he angrily struck the rock for water when he was merely supposed to touch it with his staff, gently coaxing the water from its source (see Numbers 20: 2-13.) Many read this as the explanation for his punishment.

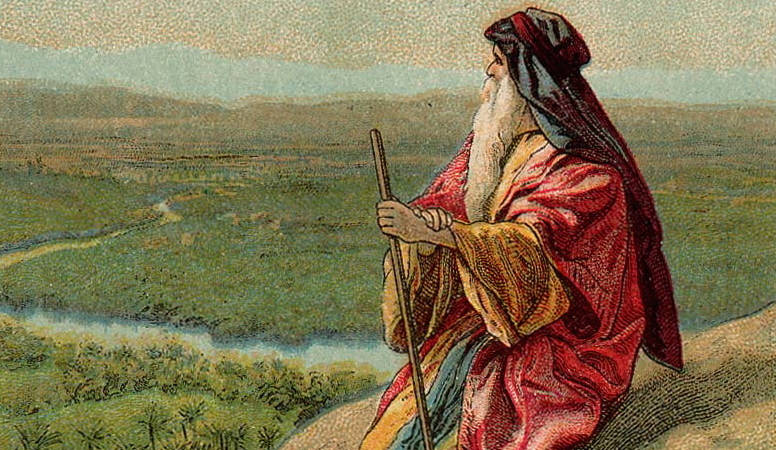

Yet Moses is taken to Mount Nebo at the end of his life and allowed to gaze into the future, a privilege none of us are given. Can this really be considered a punishment or is it simply a recognition that the past generation — and its slave mentality — has to remain in the desert?

The past must not be forgotten but it cannot be recreated. Nor can it be brought into the future. With the help of God, Moses is able to see the fruits of his labors, the dénouement of the journey of the people in the desert. He gazes across into the Land and is given the ability to see.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

We have witnessed Moses’ ability to see so many times in the past, such as when he witnessed the presence of God in the midst of a burning bush that was not consumed, but the vision described in this portion seems to be an entirely new phenomenon. It seems odd that it is introduced at the end of Moses’ life and at the end of the Torah.

Before she passed away I asked my grandmother, my bubbe, the last of the Russian generation in our family, about her life in Russia. She used whatever strength was left in her 5-foot frame and told me quite clearly, almost stridently, “We left Russia because it was terrible. I have forgotten about it. You must forget about it too.”

The nostalgic past is never as good as we would like to remember it to be. But it is a means of getting us to this place. Had she not journeyed to these shores, my family might never have experienced its freedom.

Moses has dedicated his life to a vision. He led the people out of Egypt into the desert so that they might commune with God before entering the land of promise. Perhaps his goal was the eventual destination: arriving in the land. But the Torah would not have spent so much time telling the story of the journey were it also not important.

We who are engaged in creating a new form of Jewish community should take heed of Moses’ lesson. We should give ear (literally, haazinu, the name of this portion) and pay attention to the lesson he is offering to those who will listen. The lessons of inclusion may be found in our past, but our vision for an inclusive Jewish community is part of our vision for the future.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.