Holiness or “kedushah” in Judaism comes from access to God. The Temple in Jerusalem was called the “mikdash” (holy place), and inside it was a court called the “kodesh” (the holy [area]), and inside the kodesh was the “kodesh hakodashim“, the Holy of Holies wherein the Ark of the covenant was kept. And inside the Ark of the covenant was…a text: the ten commandments, inscribed, using the Biblical metaphor, with God’s own finger. Insofar as Jewish texts reflect the revealed will of God, Jews have treated the texts themselves, like the stone tablets of the covenant, as sources of holiness.

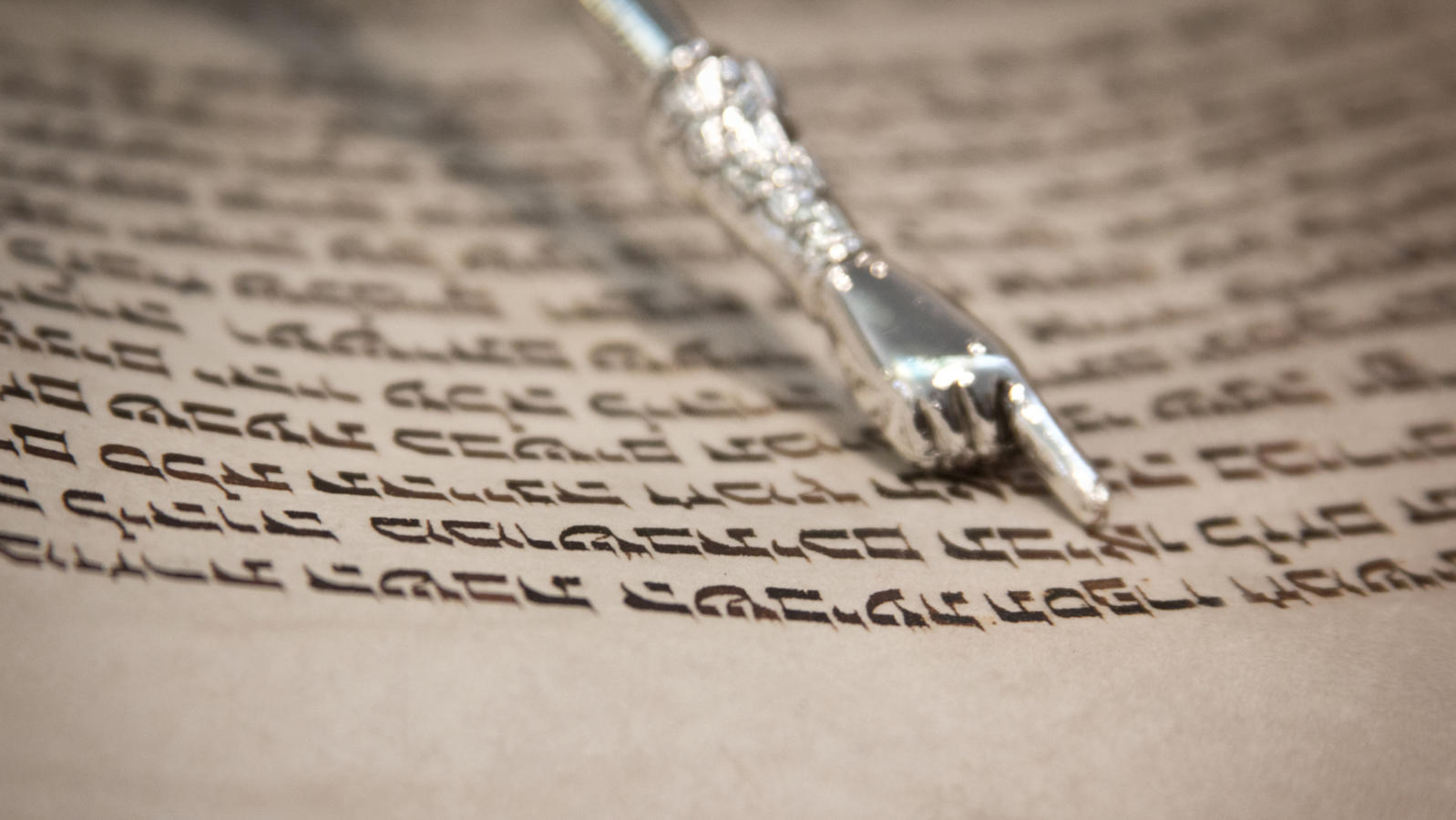

Holiness of a Jewish text inheres both in the form and the content of the text. Books are handled with great delicacy; the Rabbis forbade touching the parchment of Biblical books with bare hands. The Torah is “dressed” in wrappings and ornaments reminiscent of royalty. As a sign of respect, Jews traditionally face the Torah as it is carried in procession among the people. Different books possess different levels of sanctity, and Jewish custom even prescribes which books may be stacked on top of others.

Holiness of a Jewish text inheres both in the form and the content of the text. Books are handled with great delicacy; the Rabbis forbade touching the parchment of Biblical books with bare hands. The Torah is “dressed” in wrappings and ornaments reminiscent of royalty. As a sign of respect, Jews traditionally face the Torah as it is carried in procession among the people. Different books possess different levels of sanctity, and Jewish custom even prescribes which books may be stacked on top of others.

The Torah, as the pre-eminent sacred text, is considered perfect. Each and every letter of the Torah is invested with meaning, and that meaning is attributed to its Author. Rabbinic mythology even claims that there is meaning in the crowns on the letters (Babylonian Talmud Menachot 59b). Part of the Torah’s holiness comes from this perception that the presence or absence of apparently inconsequential words can bear meaning. Through time, this kind of close reading, and the concomitant attribution of sanctity, was applied to the Mishnah and to the Siddur as well.

Of course, the greatest expression of the sanctity of Jewish texts is the fact that their injunctions have been seen as commanding certain behaviors, and that, accounting for differences between communities, Jews have seen those commands as normative. Some Jewish scholars have divided Jewish literature into two main realms, Halakhah (lit. going, or path), which is understood broadly as Jewish behavior, and Aggadah (lit. telling), which is understood as the meaning attributed to those behaviors. It is not the case that Halakhah has a greater sanctity than Aggadah, for the two are understood as mutually reinforcing. New meanings reinforce the behavior, and adherence to the behavior and belief in the attributed meaning strengthen the sense of sanctity in the text.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

When texts are treated with normative force, and when even the least significant nuances are imbued with meaning, reading becomes a different kind of activity. Indeed, Jews seldom refer to “reading” Torah except in the sense of reciting the Torah liturgically. Sacred texts aren’t “read,” they are studied. Studying Torah is a slow process that can involve tracking the thread of ideas across and back through generations of texts, as if the footnotes and connections can retrace and uncover the sanctity of God’s own speech in the text. Torah study, and here Torah is defined in its broadest sense to include all of the conversation that study of the written Torah has generated, is of value not only because it leads to observing Torah, but in and of itself. Indeed, Torah study, the sages say, merits its own rewards, including long life, protection from danger and suffering, and forgiveness for sins. But the greatest reward for Torah study is the study itself, engaging in the process of uncovering the sanctity that the texts carry in their words and ideas.

Mishnah

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.