The transition of Yemenite women from a traditional religious society to a western-secular society upon immigration to Israel was marked by a certain ambivalence. Their status and gender roles changed, and they became integrated both economically and socially into Israeli society. However, the new values underwent a certain degree of filtration as Yemenite women accepted some elements while rejecting others. Yemen-born women found that moving to Israel put an end to some traditional symbols of femininity. Many Israeli-born Yemenite women see themselves as Israeli, their ethnic identity being only one, sometimes marginal, component of their identity. In all, they view their past through their current experiences and learn to accept and live with contradictory perceptions and realities.

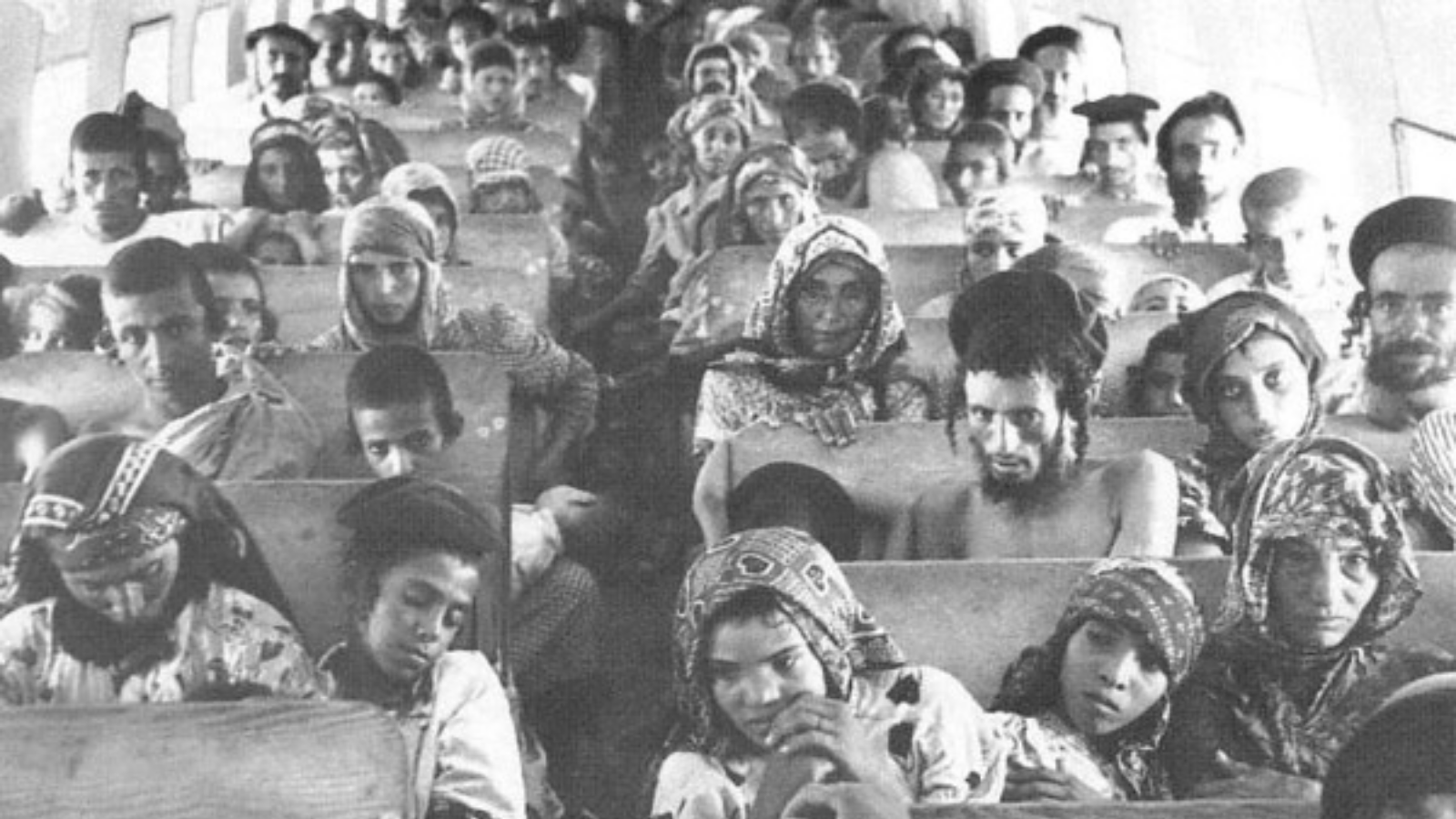

Approximately 50,000 Jews came to Israel from Yemen via Operation Magic Carpet during the period of mass immigration (1949–1950). A further 3,500 arrived between 1988 and 1996. The transition from a traditional religious society to one that was modern, primarily Western, and secular had a profound influence on the entire community and particularly on the women, whose familial and societal roles were profoundly affected.

The Early Immigration: Moshavim

After being housed in transit camps, many of the immigrants were directed to agricultural settlements (moshavim). Their acclimation in these rural settlements proved difficult, due to both their lack of agricultural experience and their traditional social structure, which went counter to the principles of the moshav. One focus of conflict was the status of the Yemenite woman and her gender roles, since moshav ideology advocated women’s full partnership in agricultural labor and social activity.

In Yemen, Jewish women did not participate in public life and their roles were restricted to childbearing and housekeeping. Authority and the ownership of property were in the hands of the men, and strict separation between the sexes was upheld. There was also a clear division of labor in the patriarchal family. Each spouse obtained support from his or her extended family in performing his or her duties and thus relied less on support and help from the spouse. In contrast to this separation, in the moshav women demonstrated extensive business initiative, which was an important factor in changing the immigrants’ tradition. Concomitantly with the system of cooperative marketing that was controlled by the men, the women developed an informal economic system. They traveled into town, sold agricultural produce at high prices, and bought products for their homes. This activity afforded economic independence, increased their power in the home, and helped them develop social networks with women outside their communities. The women were thus more exposed to different values and lifestyles than the men. These changes demonstrate how immigration conditions expose women to new opportunities that serve as a source for their empowerment.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Homogeneous Urban Settlements

Although processes of change occurred in the status of women and in family life in settlements of immigrants from Yemen, ethnic homogeneity slowed the rate of such change and contributed to the preservation of tradition.

Though there was a general tendency to preserve ethnic customs, they were not preserved in their original form: it is impossible to miss workdays in order to hold week-long premarital marriage celebrations, as was the custom in Yemen. The celebrations were therefore reduced to one evening, devoted to the henna ceremony (when the bride’s hands and feet are dyed), which is still conducted according to Yemenite tradition. However, Israeli elements gradually changed this ceremony, for example by abolishing the separation between the sexes. Such changes indicate that even a traditional society undergoes processes of change.

Since the men had difficulties in providing for their families, women worked as household help outside their settlement. Their income was usually equal to that of their husbands and sometimes they were even the main wage earners. They were also the first to come into contact with a different culture and were willing to adjust to social changes. This situation undermined family relations since the authority of the father decreased, whereas the woman’s status changed dramatically as she succeeded in coping with the new reality better than the man.

Women’s organizations that operated after the establishment of the settlements strengthened women’s status through courses and lectures. While many women participate in these activities, they sometimes feel frustrated and do not identify with messages of “women’s liberation,” which are still foreign to their cultural world.

Women Born in Yemen

The transition from an extended family to a nuclear family generated a significant change in the women who emigrated from Yemen during the 1950s. They came into contact with public institutions such as the baby-care center, kindergarten, and school, and through them became acquainted with a new social order. Their legal status also changed; they are partners in family property, polygamy is forbidden, and their consent is required for divorce.

Changes already occurred in the perceptions and behavior of the women immigrants during their early Hebrew lessons in the absorption centers. Married women accepted new roles but remained committed to traditional values. Single women, who were prepared to undergo a profound change in their lives and neglect their traditional roles, indeed underwent such a change in their cultural identity, as well as in their social identity. For example, they also studied outside the absorption centers, worked as office clerks and in education, as teachers. In addition, they changed their names to ones more common among women in Israel.

As Yemenite women began working outside the home, they became a central economic factor in the family, learned the concepts of Israeli society, and served as agents of socialization for their families. In contrast to the situation in Yemen, they also chose the women which whom they spent her free time, who became their “fictitious” relatives. The numerous social activities in which they could participate strengthened their self-esteem and increased their independence. However, their new responsibility for supporting their families does not relieve them of responsibility for the housework and care of children. Thus they enters the “public sphere,” but their husbands do not enter the “private sphere” and they find themselves doing a “double shift” of work. Hard work and coping with a strange environment put an end to some of the traditional symbols that expressed their femininity: embroidered clothes, jewelry, cosmetics and ornaments made of Yemenite perfumed herbs. Their past in Yemen also has a significant effect on their perceptions and problems in Israel. On the one hand they recognize the restrictive way in which they were brought up. On the other, they view themselves as dispensers of moral values and proper conduct and expect their daughters to behave accordingly.

Israeli-Born Women

The Israeli-born daughters actively participate in the formal institutions of Israeli youth and in the main areas of Israeli society and thus actually complete their parents’ immigration process. At school these girls learn that they can rely on their talents and can realize them — a process that increases their self-confidence. Most complete their high-school studies, with the encouragement of their home and ethnic environment.

Many of the Israeli-born women regard themselves as Israeli, their ethnic identity being only one, sometimes marginal, component of their identity. They are usually proud of their heritage and participate in some of the traditional ceremonies, although they do not always attribute to them the significance which they had in Yemen. Perceiving themselves as “modern,” they appreciate their parents but have reservations concerning their “primitive” lifestyle, which is inappropriate for the new conditions. Since their attitude towards past experiences is different, they do not face the dilemmas faced by their parents and their behavior patterns stem from the standards and expectations of Israeli society. Thus the gap created between these women and their parents is not only generational but also cultural.

Many of the Yemenite youth are not religious, but neither are they completely cut off from religion. The percentage of young people who define themselves as religious is high compared to other youngsters in Israel and many of them even define themselves as traditional. We may thus conclude that there is no “abolishing religious symbols” among the children born in Israel to Yemenite families, but rather a process of “forsaking religious symbols,” which is a more moderate form of abandoning religious values.

The Contribution of Yemenite Artists

Yemenite women’s creativity in the arts, especially in dance and music, has contributed greatly to the formation of Israeli culture. Yemenite folklore groups began to form in the 1950s, the best-known being the Inbal dance theater, founded in 1949 by Sara Levi-Tanai, who was born in Israel to immigrants from Yemen but from an early age received a European education. She worked as a kindergarten teacher on Kibbutz Ramat ha-Kovesh and wrote popular songs for young children . Her creations as a poet, composer, and choreographer combined western tradition with her Yemenite heritage. At Inbal she developed a modern dance theater that integrates elements of ethnic movement, music, and clothing. However, in contradistinction to Yemen, boys and girls danced together. Her works deal with female figures from the Bible and with the lives of women in Yemen. Rather than reconstruct the past, she drew material from it to serve as a foundation for something new: through the encounter between different cultures, she created an original Israeli dance. In 1973 she was awarded the Israel Prize for her life’s work.

Today one cannot talk about Israeli music without mentioning Yemenite singers. From the 1950s to the 1980s they were integrated into the dominant culture and performed Western material. The most prominent example of such integration is Shoshana Damari, who received the Israel Prize in 1998. However, since the 1980s Yemenite women singers have returned to their origins and are trying to create a unique style, integrating old and new. Ofra Haza, who presented Yemenite music with ethnic dress and jewelry and western instruments, achieved international acclaim as a western pop singer presenting the “eastern” spirit. Achinoam Nini, who grew up in New York and began appearing in Israel during the 1990s, also succeeded in developing an international career. In her musical performances she integrates various styles from the Yemenite, Hebrew and international repertoire and aims at being accepted as an equal in the pop culture of Israel and the world.

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.