Commentary on Parashat Pinchas, Numbers 25:10-30:1

The most common word in Parashat Pinchas points to one of its central themes: family. The Hebrew word for family, mishpacha, appears in this Torah portion over 90 times.

What, exactly, makes a family? At first glance, Parashat Pinchas certainly seems to know the answer. The portion opens with a pretty unequivocal statement of who qualifies. At the start of the reading, Pinchas is rewarded for passionately defending God by killing an Israelite man who had transgressed with a Midianite woman. The Torah makes clear that the couple had crossed a familial boundary.

The name of the Israelite who was killed, the one who was killed with the Midianite woman, was Zimri son of Salu, chieftain of a Simeonite ancestral house. The name of the Midianite woman who was killed was Cozbi daughter of Zur; he was the tribal head of an ancestral house in Midian. Numbers 25:14-15.

We learn nothing else about these two people except their familial identities. The message seems almost self-evident: crossing traditional family lines is dangerous. It leads to violence, rupture, and plague.

As if to underline this point, the text follows this story with another reminder of the centrality of family to our people. As soon as the plague is over and God’s rage has subsided, Moses and Eleazar are commanded to take a census of the people, each grouping defined by its ancestor and its clan — in other words, by its family. As the census unfolds, we learn of the many Israelite families traveling in the desert. In the next two chapters, mishpacha is repeated again and again, sometimes up to four times in a single verse.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

What is this repetition trying to teach us?

As Parashat Pinchas progresses, we come to see that the definition of family is more complicated than it originally appeared. Some of the families listed don’t look like the standard model at all.

Some have experienced loss. In Numbers 26, the Torah references the death of Korach and the tragic deaths of Aaron’s sons. In the midst of the counting, we learn that the children of a bad man live on while the children of a good man die. It is a rare family that gets by without tragedy or drama.

Others break the conventional mold in other ways. The daughters of Tzlofchad defy tradition and the established family model by declaring that they should inherit their father’s land even though he died without male heirs. They actually get the law rewritten to work with the reality of their family situation. Other possibilities for family variations are written into the law at the same time.

If a man dies without leaving a son, you shall transfer his property to his daughter. If he has no daughter, you shall assign his property to his brothers. If he has no brothers, you shall assign his property to his father’s brothers. If his father had no brothers, you shall assign his property to his nearest relative in his own clan, and he shall inherit it. Numbers 28:7-11

Indeed, the Torah offers models of connection that complement or even sidestep traditional family structures. Consider Moses and Joshua. Moses himself steps out of his traditional family unit to pass on his authority to the son of another man, Joshua the son of Nun. Moses almost never connects with his own children, instead placing his hands on his successor and granting Joshua a measure of his own authority. Joshua may be identified as the son of Nun, but the true father-son relationship in his life is with Moses. The biological family unit isn’t the only way to find deep connection and meaning. Passing on a legacy can happen in a multiplicity of ways.

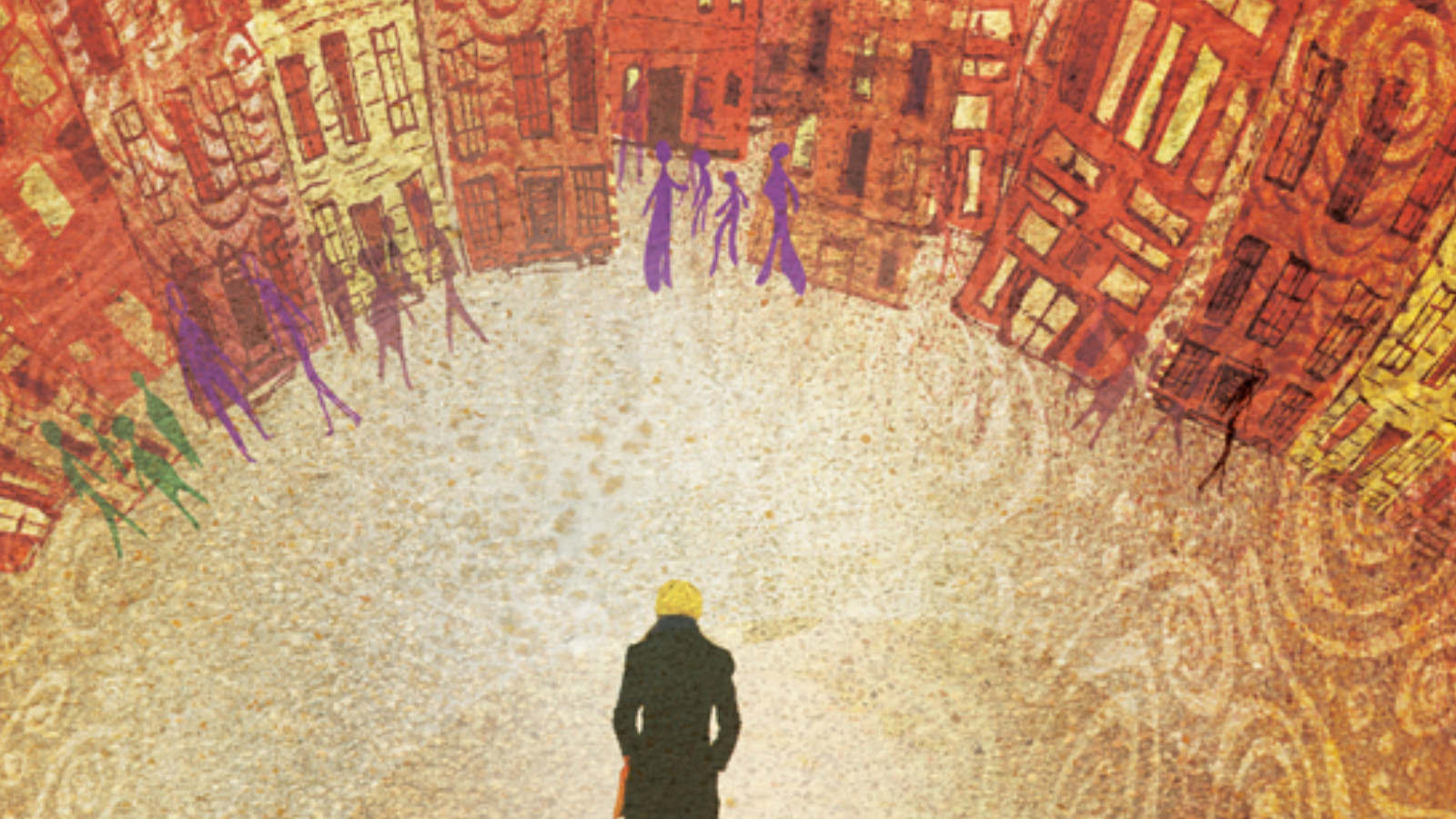

Parashat Pinchas ends with a description of the festival rites and sacrifices. Whatever the structure of the family, communal celebrations are open to all members of the wider community of Israel. It’s a powerful ending to a portion that began with a black-and-white picture who does and doesn’t belong but concludes with a more nuanced understanding of the reality of family life.

What we are left with is the ever changing nature of the Jewish family. As it evolves, so do we, finding new ways of connecting and celebrating together, and making sure that in today’s census, every type of mishpacha counts.