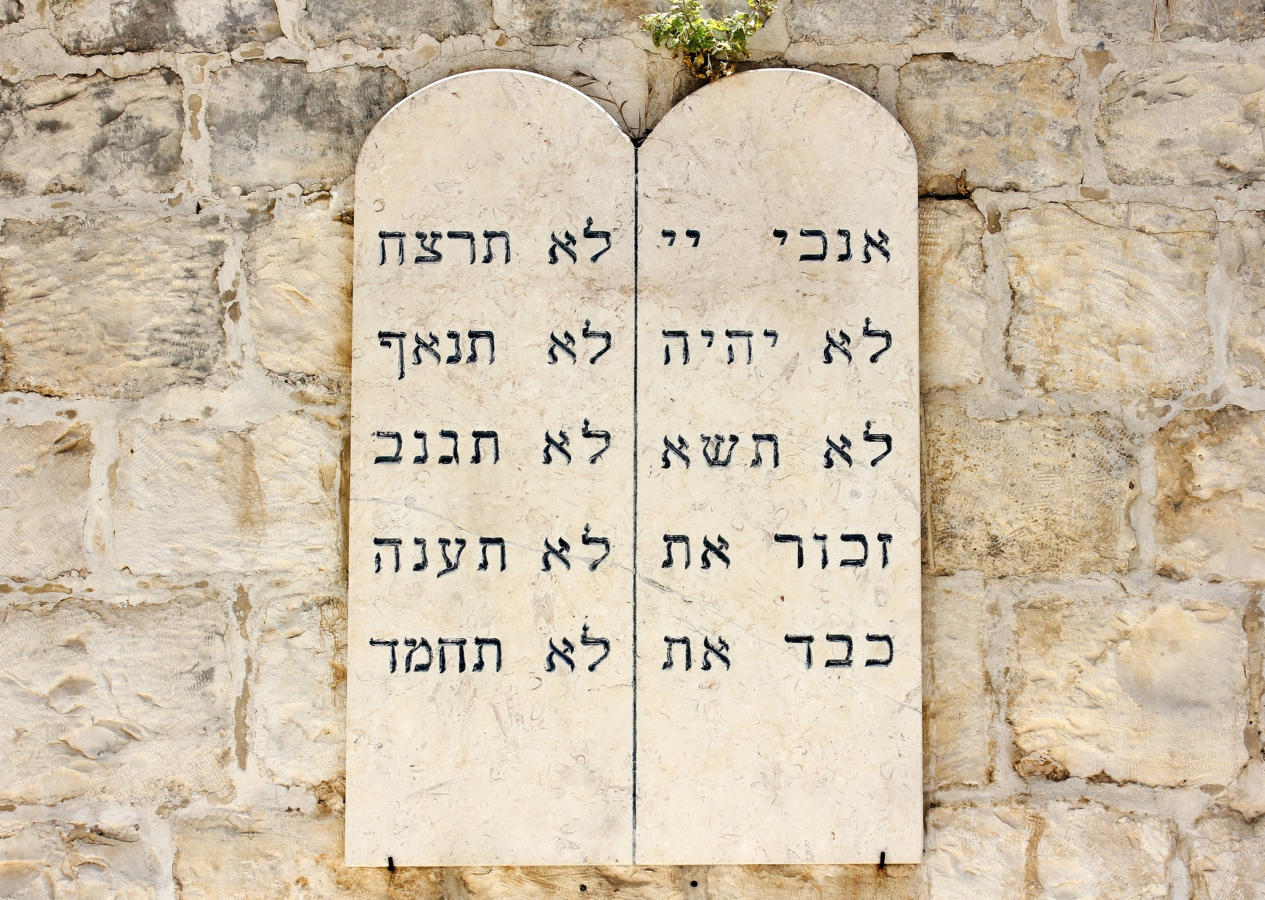

Commentary on Parashat Mishpatim, Exodus 21:1-24:18

Every year at this time it happens: I become disappointed in the Torah. Thunder and lightning and voices of revelation at Sinai are followed by the plodding specificity of the civil and religious laws of Mishpatim. The Torah goes from narrative to endless laws and detailed instructions for a good portion of the remainder of the five books.

A Real Thud

Going from Yitro to Mishpatim we come down the mountain with a real thud. Gone are the salacious family stories of Genesis and the dramatic national birth story of Exodus. Starting with this week’s Torah portion, sitting in synagogue week after week, one can hear yawns all around. What happened to the joy of sheer story? Why do we move from aggadah (narrative) to halacha (law)?

To complicate matters further: after all the suffering of the Israelites in Egypt, the very first laws of Mishpatim concern slave ownership. Not the prohibition of owning slaves, as one might want and expect, but the rules detailing the treatment of a slave, slavery an institution that is simply presumed by the text. After all that, after all those years enslaved, after witnessing the plagues, after passing through the red sea to escape slavery, why in the world are the Israelites permitted the ownership of other human beings?

One can understand this shift from Sinai to laws concerning slavery in two interrelated ways:

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Misphatim begins with the following law: “When you acquire a Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years; in the seventh year he shall go free.” (Exodus 21:2)

It’s almost as if they are given a law in which they are commanded to transform, to revolutionize their own consciousness. You can own a slave, but after seven years, you must set that slave free. You were a slave, and now you will be a master. And as a master you must liberate. As God liberated you, so must you set your slave free — a clear example of tzelem elokim (being created in the image of God), or to put it another words, imatatio dei (the imitation of God).

A Shift from Narrative to Law

The shift from narrative to law begins to have meaning in the context of this same shift of power. Until this point in the text we are told a story. We are watching these events happen to others. But, where story becomes law we are told how to live our lives. We are supremely implicated.

The very first law captures the story that the Israelites had just experienced, and yet, at the same point tells them to take control of that narrative and perform it themselves — perform exodus, perform liberation. You may be masters, but you must become liberators. Every seven years.

Indeed, the narrative that frames and shapes these laws, the narrative that gives these legal details coherence, is the narrative of liberation.

Consider for example the following verses:

“You shall not wrong a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 22:20) and “You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9).

This is what happened to the narrative. It didn’t disappear. Rather, shifting from narrative to law shifts the very nature of the text’s address. Beforehand we were reading a story that happened to others in history. Now I read the text, and I am commanded to become an actor and to act in a certain way. A way that liberates.

If I become the subject of these laws, the story doesn’t end at all. It’s just that I, the reader, I, the one addressed by this sacred text, am now at the very center of the story. It’s supremely personal. For much of the rest of the Bible we can no longer escape into a good story, because that story has become all about us. There is no escape, only exodus. Exodus and liberation. And the endless multiplying of story.

Provided by the Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel, a summer seminar in Israel that aims to create a multi-denominational cadre of young Jewish leaders.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.