Commentary on Parashat Vayishlach, Genesis 32:4-36:43

Religious thinkers throughout the ages have pondered the question, “How do people have the audacity to stand in the presence of God?” Finite in power, wisdom and longevity, human beings are paltry and insignificant when compared to a supernova or to a galaxy, let alone to the eternal Creator who fashioned those marvels. How, then, do we have the temerity to place ourselves before God, to address God, and to argue with God?

The same question might also be leveled toward the paradox of standing in the presence of another human being. Each of us is a universe in miniature — replete with our own depths and eddies, our hidden doubts and fears and talents. None can ever fully know themselves, let alone claim to truly know another person. So how do we summon the nerve to address each other with intimacy and familiarity?

The inexpressible depth of one human soul exposed to the unfathomable profundity of another, the encounter of unknown meeting ought to silence the entire universe. It is a marvel that we can reach each other at all. It is a paradox that the finite creatures, humanity, presume to call to God with hope.

A Similar Dilemma

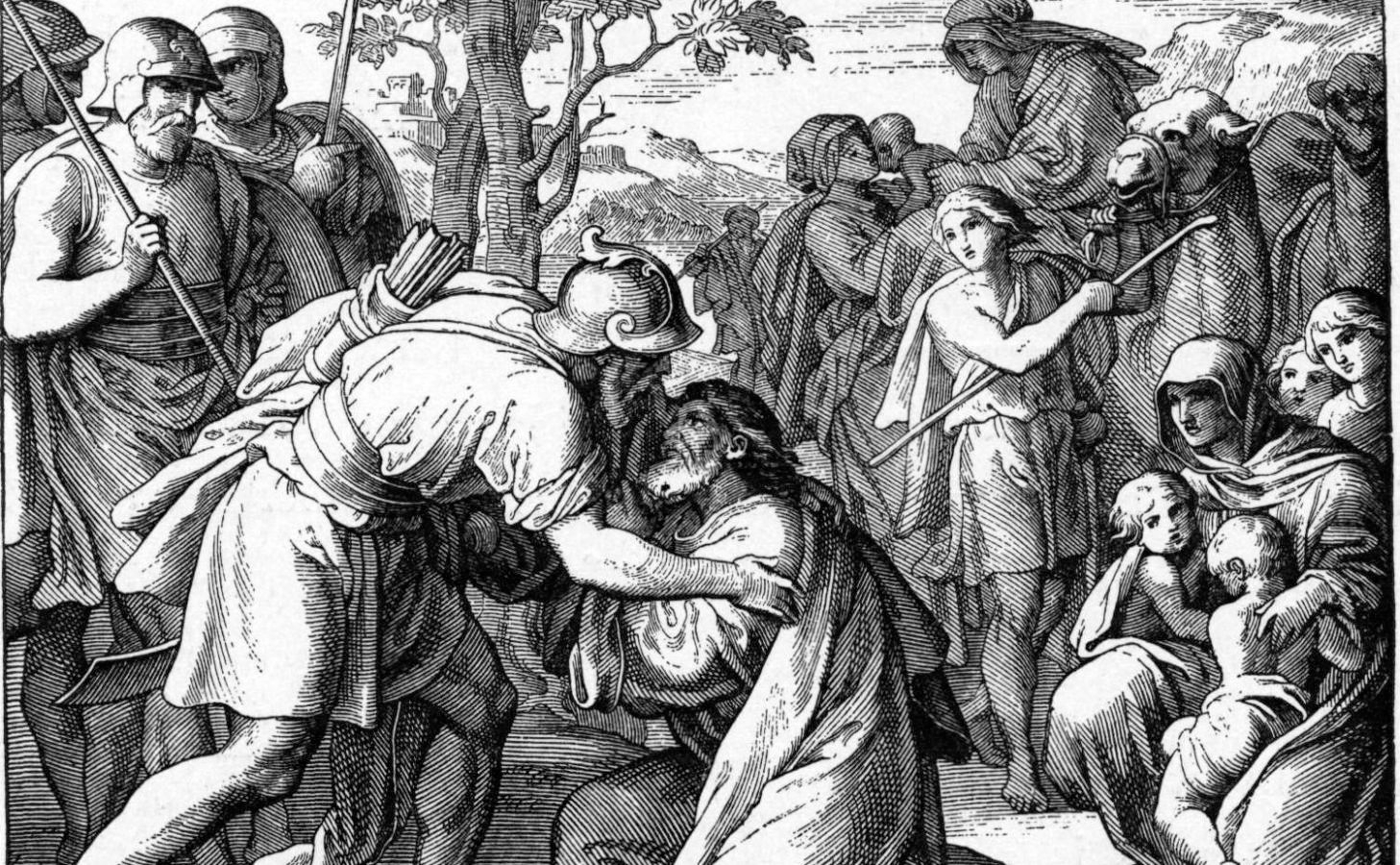

This week’s Torah portion expresses a similar dilemma, contrasting the encounter of two human beings with an encounter with the Holy Infinite One. On his way back to the Land of Israel, Jacob finally re-establishes contact with his brother, Esau. Years before, Jacob had deeply offended his brother, and now, as an adult and a sage, he hopes to restore some familial connection between them. But how can he communicate across the silence of acrimony, hidden hurt and lost years?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Jacob’s words are instructive. He presents his brother with a series of gifts and then says to Esau, “To see your face is like seeing the face of God, and you have received me favorably.” What a remarkable comment! Jacob compares greeting his brother with theophany itself, argues that exchanging words with his brother is nothing less than revelation!

So problematic was Jacob’s link of his brother and God that generations of Jewish scholars backed away from his audacious connection. Saadia Gaon (10th century Babylon) interprets Jacob’s remarks as comparing the vision of Esau to “the face of the prominent.”

Abraham ibn Ezra (12th century Spain) insists that Jacob didn’t mean God directly; he meant an angel. And Radak (13th century France), most boldly of all, argues that Jacob mentioned seeing the angel in order to intimidate Esau. If Esau thought that an angel was present, he would refrain from harming his saintly brother.

The Shocking Comparison

What can we do with Jacob’s shocking comparison? A starting point is to note that Jacob compares Esau to God not only by saying that seeing one is like seeing the other (a reminder that even an Esau is made in God’s image), but he also demonstrates that one serves them in the same way.

As the Ramban (Nachmanides) notes, one brings gifts and sacrifices to worship God, and Jacob also brought gifts and offerings to placate his aggrieved sibling. Perhaps what the Torah, and Ramban, are pointing out is that we communicate best not by relying on the superficial devices of words and thoughts, but rather by allowing our deepest parts to respond to the presence of the other.

By approaching another person with reverence and warmth (since encountering them is like seeing the face of God), by showing our openness to their concerns and their fears (presenting offerings before exchanging words) we affirm the unique marvel of each individual.

Just as God asks not to be approached empty-handed, so too, human beings should be approached with offerings of respect, affection and marvel. Each human being offers a unique embodiment of the godly and the mysterious. We, like Jacob, can make that comparison explicit, by training ourselves to encounter God in everyone we meet.

Provided by the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies, which ordains Conservative rabbis at the American Jewish University.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.