While Tu Bishvat asw we know it today came about long after the days of the Talmud, this day and its central concern, trees, are important in rabbinic literature.

The Four New Years

Rabbinic Judaism teaches that there are four new years. While there is some debate as to the exact date of each one, the consensus holds the following. The first of the month of Nisan is the new year for kings and festivals; the first of Elul is the new year for the tithing of animals; the first of Tishrei (Rosh Hashanah) is the new year for calendar years, sabbatical years, jubilee years, planting, and vegetables; and the 15th of Shvat (Tu Bishvat) is the new year for trees (Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 2b).

The primary role of a new year for agricultural items is determining what products are certified for tithing. It thus essentially represents a tax on assets that is paid through sacrifices to God and direct offerings to priests and the poor. In the aftermath of the destruction of the Second Temple, the system of four new years remains as a marker of the central role that Temple worship and tithing played in the relationship between the Jewish people and God. Each new year marks a key component of this relationship.

The New Year for Kings and Festivals represents a yearly affirmation of the social, political, and religious structure of the nation. The Temple, particularly during festivals, was the vehicle for the masses to recognize and support the leaders responsible for the cycle of sacrifices that kept the Jewish people in good stead with God. The kings ruling over the land of Israel had to ensure that this system was functional and protected. Because ancient Israel was primarily an agricultural society, temple tithing as well as other forms of cultic tribute and sacrifice consisted of the vegetables, fruits, and animals that people cultivated.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The new years of the first of Elul and Tishrei and the 15th of Shvat shared the responsibility for marking the process of generating the resources that quite literally fed the cultic system. These new years determined the larger and smaller scale cycles for planting, harvesting, and offering or consuming Israel’s most valuable goods.

While the rabbis preserved the first of Tishrei as Rosh Hashanah–celebrated today as the beginning of the Jewish calendar year as well as the start of a period of intensive individual and communal spiritual introspection and repentance culminating in Yom Kippur–the other three new years faded from Jewish practice. Nonetheless, rabbinic tradition continued to develop a rich body of texts and ideas about trees, even as the holiday of Tu Bishvat lay all but dormant for hundreds of years.

Trees in Rabbinic Thought

If the cycle of four new years provides a periodic measure for discerning how the Jewish people as a whole relates to God, trees serve as a symbol and metaphor for the spiritual choices of individuals.

A tree stood at the very center of the first human moral dilemma, when Adam and Eve ate of the Tree of Knowledge. One rabbinic tradition holds that this was a fig tree. Even though the fig tree, according to this midrash (interpretive literature), allowed Adam and Eve to doom themselves and their descendants to a life in exile from paradise, the tree also offered them the first step towards spiritual redemption, by providing Adam and Eve fig leaves to cover their nakedness (Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 70a-b). Here, and in many other rabbinic stories and interpretations, trees provide a kind of litmus test for human behavior.

According to another midrash, Honi the Circle Maker fell asleep for 70 years, only to discover that a carob tree outlives the one who plants it. Planting trees, a particularly beloved practical and symbolic act in the rabbinic imagination, hence embodies Jewish responsibility for each generation to cultivate resources for the next (Babylonian Talmud Ta’anit 23a). Such deeply practical action within a spiritual framework is magnified by the dictum of Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, “If you have a sapling in your hand and are told, ‘Look, the Messiah is here,’ you should first plant the sapling and then go out to welcome the Messiah” (The Fathers According to Rabbi Natan/Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version B 31).

Trees are among the most dependable and useful vessels to guide people to be steadfast in the face of challenges both hidden and revealed, particularly in moments of transition.

When they behave properly, people are compared to the lasting physical and spiritual stature of trees, as they are when God fells them with a thundering crash for behaving badly (Babylonian Talmud Bekhorot 45b). The life and example of trees mirror human experience, and trees are provided special protection in times of dispute (Deuteronomy20:19). In a play on one of the Hebrew words for tree or brush–siah–it is said that trees are created as friends and partners for human beings, engaging them (mesihim) in constant dialogue (Midrash Genesis Rabbah 13:2).

In the traditional liturgy for the conclusion of the Torah service, the rabbis insert the verse, “She is a tree of life to them that grasp her, and all who hold onto her are happy” (Proverbs 3:18). This saying epitomizes rabbinic tradition’s most famous metaphorical use of the tree–as a symbol of Torah. Throughout the rabbinic canon, texts refer to the Torah as a tree of infinite knowledge, producing the fruits of new teachings and students over the generations.

Because no Jewish object or concept garners more respect or is more central than the Torah within rabbinic tradition, it is illuminating that the Rabbis choose the tree as a primary symbol for the presence of Torah in the world. If humanity’s failure of the moral litmus test at the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden sets humankind on its journey into the world beyond paradise, the Tree of Life of Torah emerges as the source of protection, sustenance, and proper living that allows humankind to continually reconnect with its highest self.

Elul

Pronounced: eh-LULE, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish month usually coinciding with August-September.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

Nisan

Pronounced: nee-SAHN, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish month, usually coinciding with March-April.

Rosh Hashanah

Pronounced: roshe hah-SHAH-nah, also roshe ha-shah-NAH, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish new year.

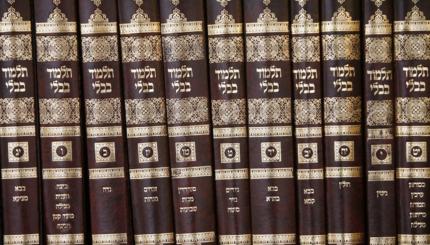

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Tishrei

Pronounced: TISH-ray, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish month, usually coinciding with September-October.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Tu Bishvat

Pronounced: too bish-VAHT (oo as in boot), Origin: Hebrew, literally "the 15th of Shevat," the Jewish month that usually falls in January or February, this is a holiday celebrating the "new year of the trees."