There is simply no describing the plaintive, moving melody to which Yiddish writer Avraham Reisen’s poem was set. As a song, it is familiar to many of us who know it thanks to immigrant parents or grandparents. And, remarkably, the strains of "A Sukkeleh," no matter how often we may have heard them, still tend to choke us up.

Based on Reisen’s "In Sukkeh," the song, whose popular title means "A Little Sukkah," really concerns two sukkot, one literal, the other metaphorical, and the poem, though it was written at the beginning of the last century, is still tender, profound and timely.

Thinking about the song, as I–and surely others–invariably do every year this season, it occurred to me to try to render it into English for readers unfamiliar with either the song or the language in which it was written. I’m not a professional translator, and my rendering, below, is not perfectly literal. But it’s close, and is faithful to the rhyme scheme and meter of the original:

A sukkaleh, quite small,

Wooden planks for each wall;

Lovingly I stood them upright.

I laid thatch as a ceiling

And now, filled with deep feeling,

I sit in my sukkaleh at night.

A chill wind attacks,

Blowing through the cracks;

The candles, they flicker and yearn.

It’s so strange a thing

That as the Kiddush I sing,

The flames, calmed, now quietly burn.

In comes my daughter,

Bearing hot food and water;

Worry on her face like a pall.

She just stands there shaking

And, her voice nearly breaking,

Says "Tattenyu, the sukkah’s going to fall!"

Dear daughter, don’t fret;

It hasn’t fallen yet.

The sukkah will be fine, understand.

There have been many such fears,

For nigh two thousand years;

Yet the sukkahleh continues to stand.

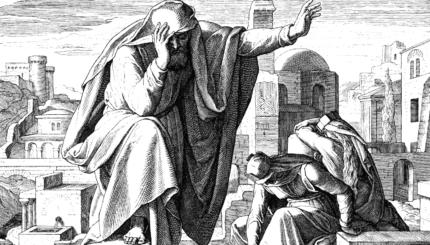

As we approach the holiday of Sukkot and celebrate the divine protection our ancestors were afforded during their 40 years’ wandering in the Sinai desert, we are supposed–indeed, commanded–to be happy. We refer to Sukkot, in our Amidah prayer, as "the time of our joy."

And yet, at least seen superficially, there is little Jewish joy to be had these days. Jews are brazenly and cruelly murdered in our ancestral homeland, hated and attacked on the streets of European cities–and here in the United States, our numbers are falling to the internal adversaries of intermarriage and assimilation.

The poet, however, well captured a Sukkot-truth. With temperatures dropping and winter’s gloom not a great distance away, our sukkah-dwelling is indeed a quiet but powerful statement: We are secure because our ultimate protection, as a people if not necessarily as individuals, is assured.

And our security is sourced in nothing so flimsy as a fortified edifice; it is protection provided us by G-d Himself, in the merit of our forefathers, and of our own emulation of their dedication to the divine.

And so, no matter how loudly the winds may howl, no matter how vulnerable our physical fortresses may be, we give harbor to neither despair nor insecurity. Instead, we redouble our recognition that, in the end, G-d is in charge, that all is in His hands.

And that, as it has for millennia, the sukkah continues to stand.

© AM ECHAD RESOURCES

Avraham

Pronounced: AHVR-rah-ham, Origin: Hebrew, Abraham in the Torah, considered the first Jew.

Kiddush

Pronounced: KID-ush, Origin: Hebrew, literally holiness, the blessing said over wine or grape juice to sanctify Shabbat and holiday.

sukkah

Pronounced: SOO-kah (oo as in book) or sue-KAH, Origin: Hebrew, the temporary hut built during the Harvest holiday of Sukkot.

Sukkot

Pronounced: sue-KOTE, or SOOH-kuss (oo as in book), Origin: Hebrew, a harvest festival in which Jews eat inside temporary huts, falls in the Jewish month of Tishrei, which usually coincides with September or October.