Here’s an irony: Yom Kippur is among the most widely observed of the Jewish holidays, yet for a majority of Jews, it’s also the most alienating.

Consider: Shabbat is largely about rest, Sukkot is about the cycles of ecology, Passover is about freedom. All relatable and relevant concepts that don’t depend on a belief in God, let alone belief in a judging, male-identified God who reviews your good and bad deeds like a cosmic Santa Claus.

But Yom Kippur? Sin, repentance, expiation, guilt, judgment, reward, punishment, self-abnegation, penitence. Not only are these concepts largely meaningless for non-traditional Jews, but many of us find them actively harmful to our well-being and our relationships with others. Throw in some incomprehensible hymns, conspicuous consumption (on a day of self-abnegation, no less) and fundraising, and it can all seem profoundly foreign.

(Of course, many synagogues are awesome. But even they are often hamstrung by traditionalist demands, rhetorics of sin, and lengthy liturgy.)

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

To be sure, it is salutary to review one’s conduct, apologize to those one has hurt, and see if it’s possible to do better in the future. There is also a cathartic power to fasting that transcends the rational mind. If you set aside the objectionable and offensive parts, there are profound spiritual practices connected to Yom Kippur.

But that’s not what I want to talk about. I don’t want to dissipate the foreignness of Yom Kippur by making it somehow relatable. On the contrary, I want to make it more foreign.

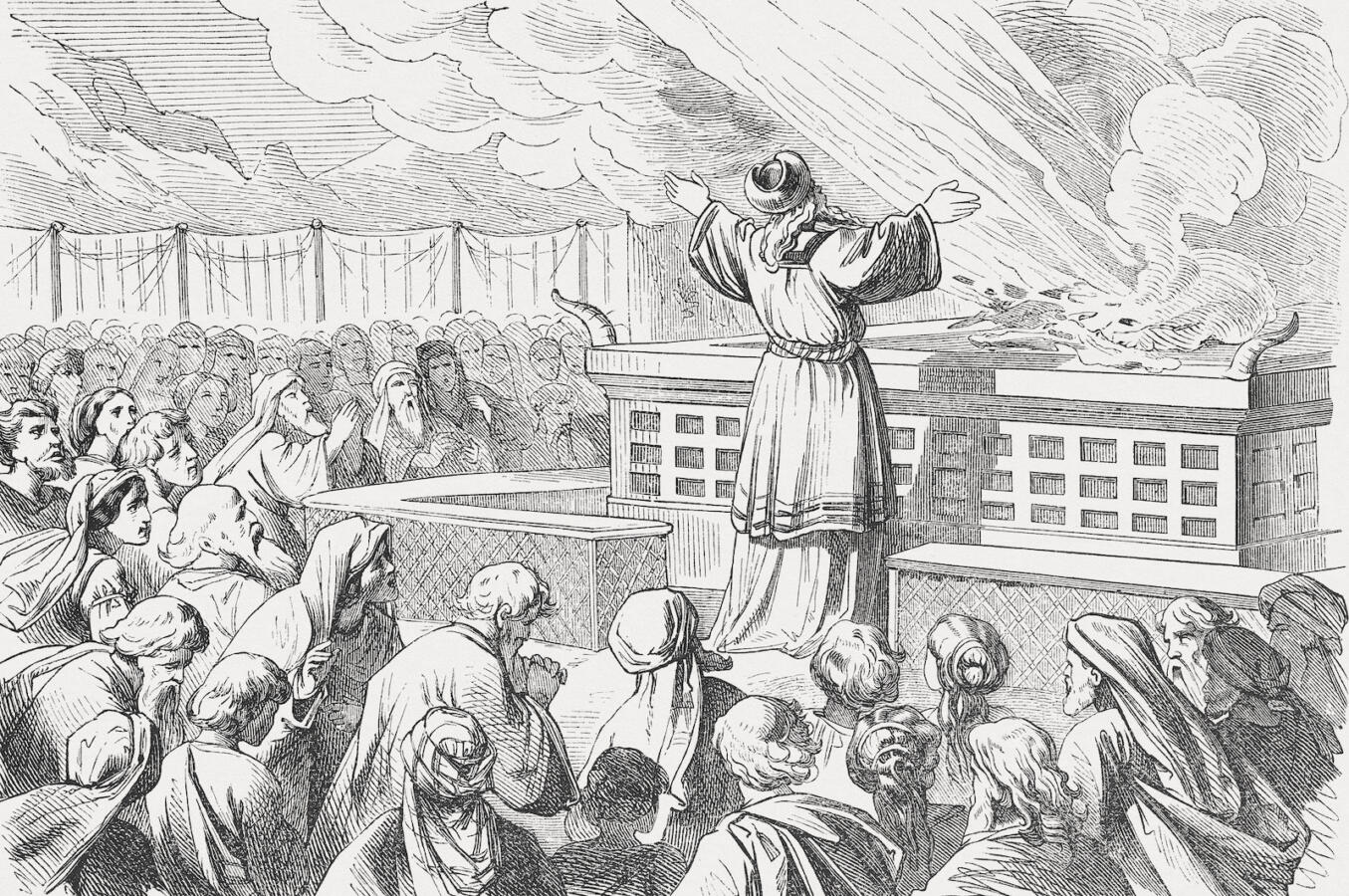

Let’s imagine — based on textual sources but with a fair amount of additional speculation — what it might have been like to be a premodern, preliterate Jew 2,000 years ago witnessing the Yom Kippur ritual in the Temple in Jerusalem. There is a series of carefully choreographed sacrifices, with blood anointed on the altar. There is a literal scapegoat pushed over a cliff, its bones shattering on the rocks below. There is the utterance of the ineffable name by the High Priest, a magical incantation that occurred at only this time each year. There is a sacred red thread that supposedly turns white when God accepts the atonement of the people. And after expiation is achieved — not by reflection and introspection, but by a mysterious, cultic ritual — there was dancing, singing, and (according to one source) public sex among the outcroppings of the Judean Hills.

I don’t know about you, but this is not my synagogue’s Yom Kippur. What could it possibly have meant to witness such an event? For me, the answer lies in precisely the least acceptable aspects of Yom Kippur’s theology: the postulation of divine justice that rewards good behavior and punishes evil.

This was philosophically untenable centuries before the Holocaust rendered it obscene. Surely, it is obvious that evil people prosper while good ones suffer — and unlike other religious traditions, biblical Judaism doesn’t defer its theodicy to an afterlife or future lives. Biblical Israelite religion clearly meant what it said: Obey the commandments, the crops thrive. Disobey, and they wither. (Deuteronomy 28:1-4)

I assume that counterfactual evidence was as available in the Iron Age as it is today. Yet imagine the comfort of believing that there was a God who brought order out of chaos, an order that is moral as well as physical. We have irrevocably lost this belief today, but I love to imagine its consolation.

After all, we are once again living in precarious times. True, our life expectancy is far greater than it once was, and modern medicine is a miracle, even if many of our brethren refuse it. But we have all been reminded of our vulnerability in these years of plague. We’ve suffered loss, fear, and a kind of existential anxiety that the privileged among us (myself included) had not encountered before. We’ve seen how institutions and relationships we thought to be secure are, in fact, not. And we know now, in a way most of us did not before, that our planet’s climate has been profoundly disturbed by human influence, with disastrous consequences now and yet to come.

The cultic magic of biblical Yom Kippur is like a desperate plea for order in a disordered world. Its very absurdity — five sprinkles of blood and we are saved, but not four and not six — points to the groundlessness of that hope. Yet the hope is fervent nonetheless, as is our knowledge that as human beings, we are incapable of living up to the ideals to which we hold ourselves.

We wish the world had a moral order to it, even as we suspect it does not, and even as we know that we ourselves could not live up to it. This is the drama of Yom Kippur.

When I attune myself to the strangeness of Yom Kippur, I paradoxically feel closer to it. I am no longer in a world of untenable theodicy and psychological abuse. I am in a strange and magical universe in which I may not believe, but which I can imagine my distant forebears inhabiting. Imagine what it was like to live as precariously as they did, as close to death and disorder. Imagine what it was like to participate in a collective ritual of catharsis, yearning to balance the scales.

I cannot make the penitential Yom Kippur cohere, but in these ancient, primal, and newly relatable stirrings of the heart, I can hear the shofar’s call.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on Sep. 11, 2021. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.