Periodically, scholars survey historians’ opinions as to what is the most influential event of all time. In recent decades, the Industrial Revolution has often appeared at the top of the list. For the politically oriented, not uncommonly the French Revolution wins; for Marxists, the Russian Revolution. Christians often point to the life and death of Jesus as the single most important event of history. For Muslims, Mohammed’s revelations and his hegira [exile, 622 CE] have a similar transcendental authority.

Yet when Jews observe Passover, they are commemorating what is arguably the most important event of all time — the Exodus from Egypt. If for no other reason than the fact that the Exodus directly or indirectly generated many of the important events cited by other groups, this is the event of human history.

That it was a Jewish event is an eloquent tribute to the extraordinary role the Jewish people — so minute a fragment of the human race — have played in human history.

READ: Exodus: History or Mythic Tale?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Exodus transformed the Jewish people and their ethic. The Ten Commandments open with the words, “I am the Lord your God who took you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.” Having no other God means giving no absolute status to other forms of divinity or to any human value that demands absolute commitment. Neither money nor power, neither economic nor political system has the right to demand absolute loyalty. All human claims are relative in the presence of God. This is the key to democracy.

Justice

Exodus morality meant giving justice to the weak and the poor. Honest weights and measures, interest-free loans to the poor, leaving part of the crops in the field for the stranger, the orphan, and the widow, treating the alien stranger as a native citizen — these are all applications of the Exodus principle to living in this world.

Thus, the Exodus, as articulated at Sinai, transformed the Jewish people and their religious ethical system. Inasmuch as Christianity and Islam adopted the Exodus at their core, almost half the world is profoundly shaped by the aftereffects of the Exodus event.

In modern times, the image of redemption has proven to be the most powerful of all. The rise of productivity and affluence has heightened expectations of the better life. Widely disseminated scientific ideas and conceptions of human freedom carry the same message: do not accept disadvantage or suffering as your fate; rather, let the world be transformed! These factors come together in a secular concept of redemption. By now, humans are so suffused with the vision of their own right to improvement that any revolutionary spark sets off huge conflagrations. In a way, humane socialism is a secularized version of the Exodus’ final triumph. The liberator is dialectical materialism, and the slaves are the proletariat–but the model and the end goal are the same. Indeed, directly revived images of the Exodus play as powerful a role as Marxism does in the worldwide revolutionary expectations. In South America, the theology of liberation directly touches the hundreds of millions who strive to overcome their poverty.

Ongoing Experience

The secret of the impact of the Exodus is that it does not present itself as ancient history, a one-time event. Since the key way to remember the Exodus is reenactment, the event offers itself as an ongoing experience in human history. As free people relive the Exodus, it turns memory into moral dynamic. The experience of slavery that breaks and crushes slaves does not destroy free people. It evokes feelings of repulsion and determination to help others escape that state.

As participants eat the bitter herb, they remember the heartbreaking tale and the death of the children. They also remember that slavery gradually conditions people to accept servitude as the norm. The Israelites fell into that trap and were delivered, not by their own merit. The lesson is that a slave needs help to get started on liberation.

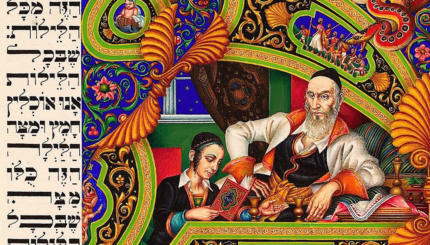

In the seder ritual, the family also acts as the transmitter of memory. The past is not excised but becomes an active part of the lives of the participants. Parents tell the story to children. At the same time, the children are not merely dependent. They ask questions and participate in the discussion. They must become involved for it is essential that they join in the unfinished work of liberation. This is why when Pharaoh offered to let the adult Jews leave Egypt to worship God if the children were left behind, Moses rejected the offer, “With our youth and our elders we will go.”

The seder order is deliberately designed to hold the children’s attention, to fascinate them with their people’s history so that they will feel impelled to take up the covenantal task. Thus, by the magic of shared values and shared story, the Exodus is not some ancient event, however important, it is the ever-recurring redemption. It is the event from ancient times that is occurring tonight; it is the past and future redemption of humanity. The Exodus is the most influential historical event of all time because it did not happen once but recurs whenever people open up and enter into the event.

Reprinted with permission of the author from The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays.

Prep for Passover like a pro with this special email series. Click here to sign up and you’ll receive a series of helpful, informative, and beautiful emails that will help you get the most out of the holiday.

seder

Pronounced: SAY-der, Origin: Hebrew, literally "order"; usually used to describe the ceremonial meal and telling of the Passover story on the first two nights of Passover. (In Israel, Jews have a seder only on the first night of Passover.)