Samuel is the third book in the Neviim (Prophets), the second section in the Hebrew Bible. In English Bibles, the book is usually divided into First and Second Samuel, but in Jewish tradition, Samuel is one book.

Read the Books of Samuel in Hebrew and English on Sefaria.

Samuel is both a historical and literary work. It begins with the leadership of the prophet Samuel, the last of the pre-monarchic rulers of Israel, and continues with the narratives of King Saul and King David. Most of the book focuses on the rise and fall of King David. Since there is no extra-biblical attestation for the events in the book, it is not considered “historical” by critical scholars. Nevertheless, the book records a critical period in Israelite history, the transition from charismatic leadership, with leaders appointed at times of need, to an established, dynastic monarchy, politically uniting the Israelites.

It is clear from the archeological remains at Hazor and Gezer that a strong monarchy existed in Israel during the 10th century B.C.E. (the period corresponding to the reign of Solomon, son of David). The historicity of the Davidic house cannot reasonably be doubted since the discovery in 1993 of the Tel Dan inscription, which dates from 841 B.C.E. and mentions “[Ahaz]iah, king of the house of David.”

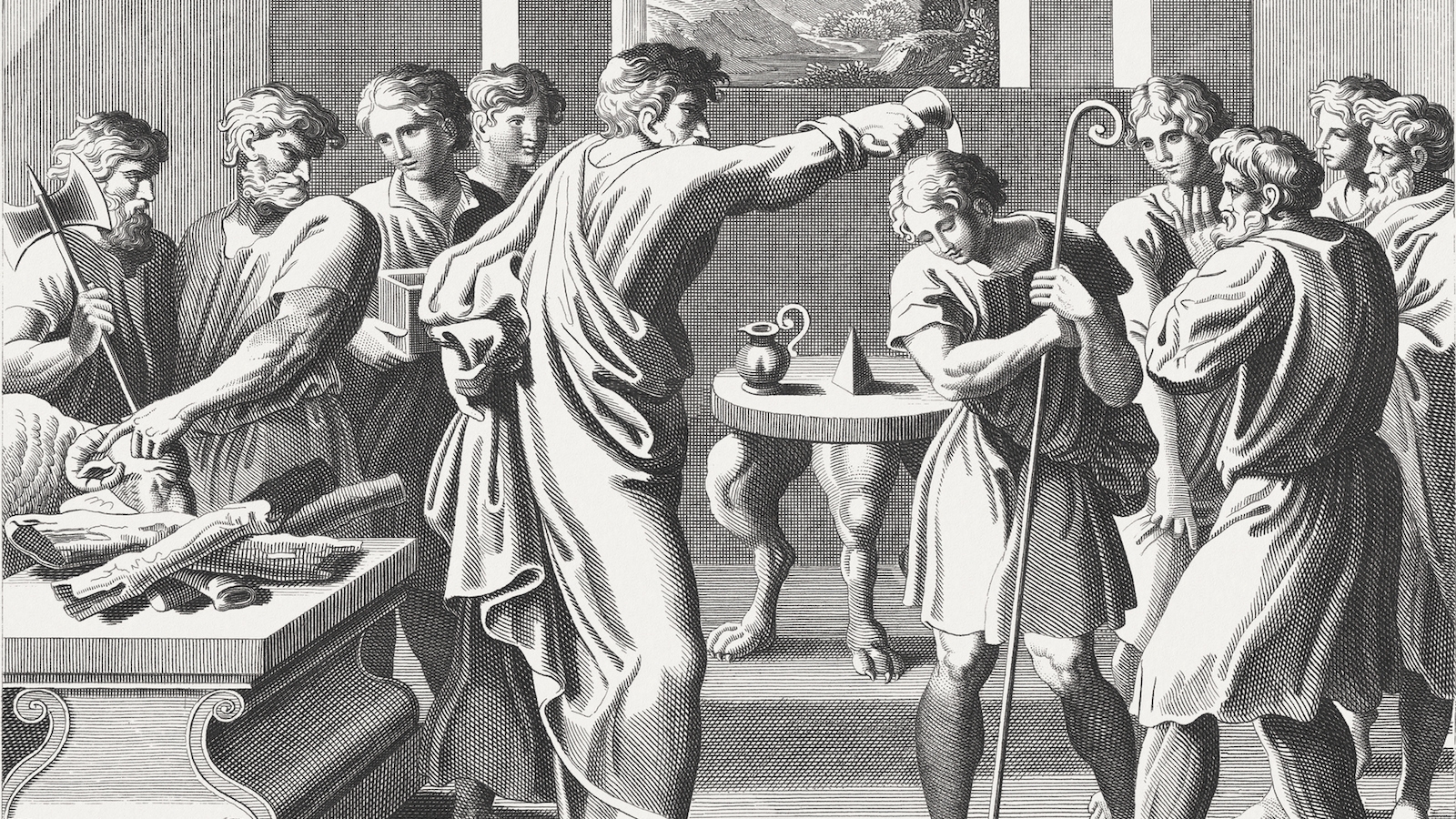

Appointing a King

Samuel portrays the inherent tension in Israelite monarchy–the tensions between obedience to God and practicality, between acting in accordance with moral imperatives and acting with political expediency. The first example of this appears in I Samuel 8, when the Israelites demand that Samuel appoint a king. The demand is anchored in practicality: “So that we too may be like all other nations, that our king may lead us and go before us and fight our wars” (8:20). Samuel had both practical objections to this plan (the king will abuse his taxation and expropriation powers) and objections of principle (“the Lord your God is your king,” I Samuel 12:12).

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

God orders Samuel to appoint Saul as king, but tension between obedience and political expediency erupts almost as soon as Saul is anointed. Saul’s principal task was to fight the Philistines, the coastal people who sought to conquer the territory of Israel in the 11th and 10th centuries B.C.E. Samuel ordered Saul to wait for him at Gilgal , so Samuel could offer a sacrifice before the war began (I Samuel 13:8-9). Saul waited seven days, but, watching the Israelites melt away day after day, he resolved to take matters into his own hands and offered the sacrifice himself. For this act of insubordination, Samuel says to Saul: “Your kingdom shall not continue; the Lord has sought out a man after his own heart, and the Lord has appointed him to be prince over his people, because you have not kept what the Lord commanded you” (13:14).

The Rise of David

This “man after his own heart”–David–began his career in Saul’s employ, and is depicted as Saul’s rival in the hearts and minds of the people. Saul understandably felt threatened by this upstart, and pursued David, who had his own regiment of supporters, throughout the deserts. Two episodes in the conflict between the House of Saul and the House of David highlight the tension between morality and expediency:

1) During the pursuit, David caught Saul unawares in a cave, and cut off the corner of his cloak instead of killing him (I Samuel 24). David claims to have acted morally, saying “See that there is no evil or sinfulness in my hand, and I have not sinned against you, and you are hunting for my soul to kill me,” in I Samuel 24:12. But this action was also politically advantageous to David. Firstly, because the act of cutting the corner of someone’s cloak was not a neutral one: It signified the end of the wearer’s kingdom (II Samuel 15:28); and secondly because David’s chances of gaining the public’s support probably depended upon his not being seen as Saul’s murderer.

2) Saul was killed in battle with the Philistines (for whom David was working at the time, though the text recounts that he did not participate in the battle). One of Saul’s surviving sons, Eshbaal, was named king over the northern tribes of Israel, while David was appointed king by the tribe of Judah, in the area south of Jerusalem. But David quickly took over the northern throne as well: Rebels murdered Saul’s son, and David’s general Joab murdered Saul’s general, the power behind Saul’s son. David took pains to distance himself from each of these murders, and publicly punished the rebels who killed Saul’s son.

On the face of it, David cannot be convicted of the destruction of the House of Saul. However, some modern scholars have raised the question of regicide on David’s part, which is a matter of some discomfort, given that later biblical tradition (e.g., Chronicles) and rabbinic tradition have tended to idealize David, and to portray him as an unwaveringly moral character. Part of the scholarly evidence suggesting David’s responsibility is that one may read, in this part of the book, an anti-Davidic political subtext. The narrative seems to go a long way out of its way to raise, in order to discount, all the evidence needed to suggest David was responsible for the fall of Saul’s entire house. In any case, David had the means and motive, and his public objections to the Saulide deaths serve primarily his potential legitimacy to sit on Saul’s throne. The fact that the other Saulide heirs who might have threatened David’s kingship are later executed for an obscure crime (II Samuel 21) seems to support this conjecture.

Others contend that David genuinely deplored the violent deaths of Saul, his son, and his general. In any case, whoever was responsible, David did profit from the elimination of the rivals to his rise to power, and as a result of these deaths, David became king over all of Israel.

A “House for God”

One of David’s first acts as king was to seek to build a “House for God” in which the ark of the covenant might be housed (I Samuel 7:2). Perhaps because of the various political machinations to which David was to some degree connected, God refused to allow David to build this house. (No reason is given for God’s refusal in the book of Samuel, but in I Chronicles 22:8, the blood that David is said to have spilled is cited as the reason.) In II Samuel 7:12-13, God tells David: “I shall establish your seed after you who shall go forth from your loins and I shall make steady his kingdom. He shall build a House for My name.” Thus this task fell to his son Solomon, but David did establish Jerusalem as the royal city and political capital of Israel.

As king, David established Israelite hegemony in the land of Israel. The Philistines and the trans-Jordanian kingdoms of Edom and Moab were subdued, and several of the Aramean kingdoms became vassals or allies of David. I Samuel 8:15 tells how David “would dispense justice and righteousness to all of his people.”

Critiques of David

The text centers David’s greatest failings in the personal realm. II Samuel 11:1 tells how “at the turn of the year, at the time when the kings go out [to war], David sent Joab and his servants with him, and all of Israel, and they destroyed the Ammonites, and encamped upon the city of Rabbah, while David dwelled in Jerusalem.” The verse contains an implicit critique of David for remaining in the city, while his devoted servants are “toughing it” in the battlefield.

The next verse sharpens the critique: “At evening, David rose from his bed and walked upon the roof of the king’s house, and saw a woman washing from upon the roof.” Nothing explicit is said to criticize David for unmanly behavior in avoiding going to war or for laziness, but the way the verses juxtapose the Israelites encamping on Rabbah with David remaining in Jerusalem and arising from his bed at evening gives the reader the impression that David behaved badly.

The woman washing was Bathsheba, whom David took into his own bed. He caused her husband–who was one of David’s military officers–to be killed in battle, and then tried to conceal both his adultery and the murder. However, this account of the beginning of David’s downfall does not justify the utilitarian value of this cover-up, and condemns David’s moral failings. A prophet acting as God’s emissary announced David’s punishment to him: “The sword shall not depart from your house for ever” (II Samuel 12:10).

This prophecy was fulfilled in David’s last years, as one son raped his half-sister and was killed for his crime by another son (II Samuel 13), who later rebelled and attempted to usurp David’s throne (II Samuel chapters 15-19). A further rebellion broke out in the north, threatening the fragile union of North and South (II Samuel 20) foreshadowing the union’s complete breakdown after Solomon, leaving only Judah in the hands of the Davidides.

ark

Pronounced: ark, Origin: English, the place in the synagogue where the Torah scrolls are stored, also known as the aron kodesh, or holy cabinet.