Commentary on Parashat Beshalach, Exodus 13:17-17:16

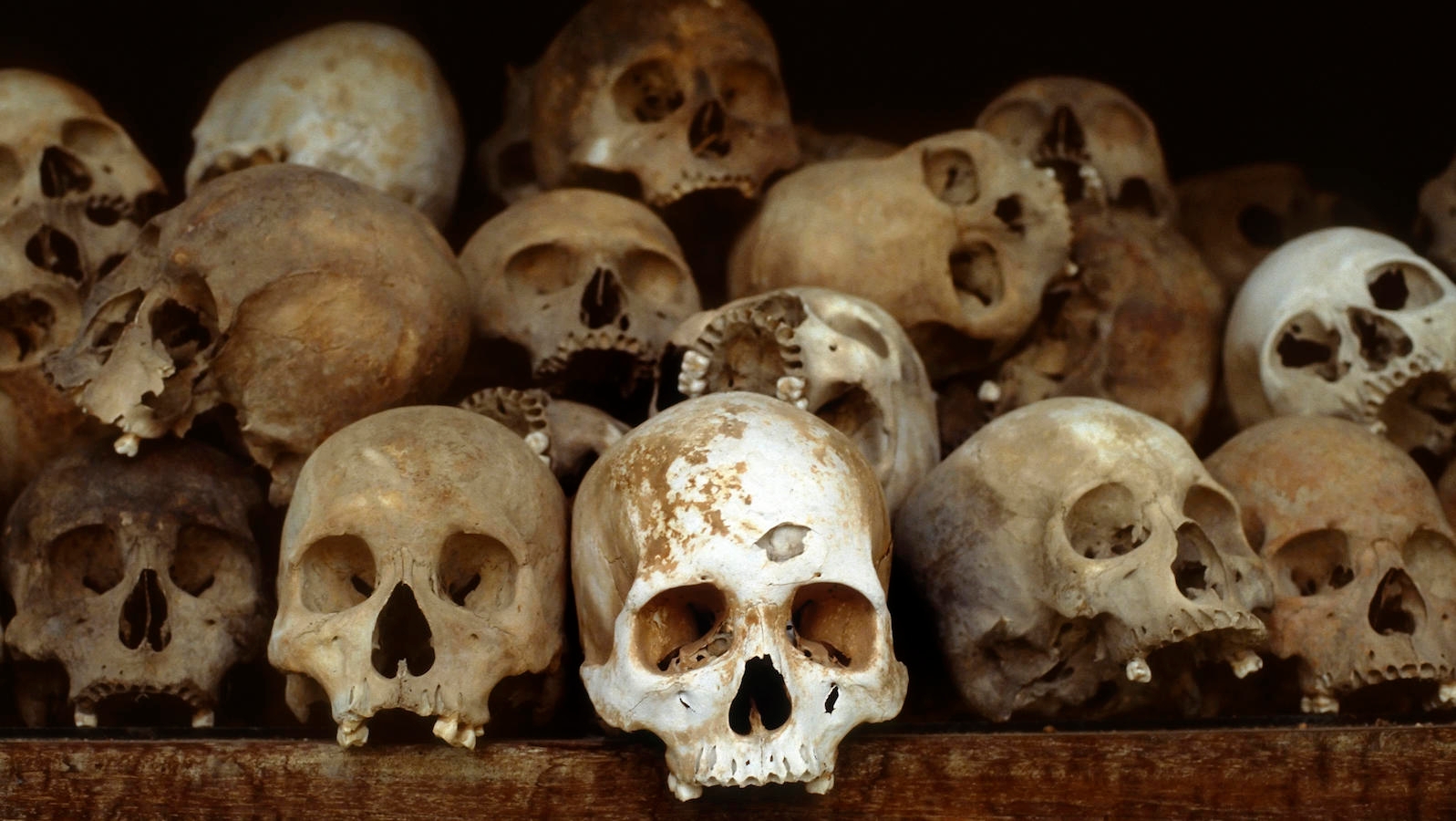

I arched my head back and looked up at a tower of nearly 9,000 human skulls. Rising 62 meters into the air, stacked and piled and encased in glass, the skulls belonged to Cambodians murdered during the Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s. This upsetting memorial now stands in the infamous “Killing Fields,” where prisoners were butchered after enduring torture at Tuol Sleng, the Khmer Rouge’s interrogation compound in Phnom Penh.

It has been a couple of years since I visited Tuol Sleng and the Killing Fields. But my memories of the piles of bones came tumbling back when I encountered a Midrash on Parashat Beshalach. The Torah portion tells us that following the Exodus, God did not lead the Israelites on a direct route to the Promised Land, through the land of the Philistines, lest the Israelites have “a change of heart when they see war.” The Midrash suggests what vision of “war” they would have seen: the bones of 300,000 Israelites from the tribe of Ephraim, laying “in heaps on the road.”

A Troubling Midrash

This troubling midrash relates a tradition that some or all of the tribe of Ephraim died in the wilderness. Having miscalculated the end of the 400 years of slavery which God prophesied to Abraham, they left Egypt on their own, 30 years ahead of schedule, and were slaughtered by the Philistines. God circumvents the scene of this tragedy, believing that the rest of the Israelites, having just emerged from their long period of oppression and violence, are not ready to encounter the sheer horror of these skeletons. As the midrash states, “Therefore the Holy Blessed One reasoned: If Israel behold the bones of the Ephraimites strewn in the path, they will return to Egypt.”

Confronting the bones of the past has taken on new urgency in Cambodia recently, as the former commander of Tuol Sleng, known as Comrade Duch, has stood trial for the atrocities that took place. The trial has offered an opportunity for the Cambodian public to revisit the scenes of horror from that era, but it has also raised difficult questions about the usefulness of these revelations in a developing country that is still struggling with profound and immediate challenges, including deep poverty and public health crises.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Post-Conflict Justice

Since 1979, at least 60 countries have been involved in what is called post-conflict justice (also known as transitional justice)—trials, truth commissions and other processes designed to “address legacies of past human rights abuses, mass atrocity, or other forms of severe social trauma, including genocide or civil war, in order to build a more democratic, just, or peaceful future.” Countries that engage in transitional justice must weigh the possibility that such efforts will result in despair, distraction or renewed violence. As one Cambodian survivor recently wrote about Comrade Duch’s trial:

It will only stir more anger and misery and hate… Around 70 percent of Cambodia’s population is under 30 years old. They didn’t experience the Killing Fields, and they face enough challenges in their daily struggle to make ends meet.

Similarly with the Israelites, God worries that as they begin to move toward a new life, the people will confront the terrible toll of a previous attempt at freedom and will abandon their own journey. Yet Jewish tradition holds out hope that the horrors of the past may eventually be redeemed. The Talmud records the possibility that the bones of the Ephraimites were the same bones that the prophet Ezekiel later saw in his famous vision:

[God] took me out by the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the valley. It was full of bones … there were very many of them spread over the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, “O mortal, can these bones live again?” I replied, “O Lord God, only You know.”

Ezekiel’s plaintive reply suggests to us the humility with which we must approach post-conflict justice, which “requires balancing pressing moral demands for action with a recognition of the practical and political limitations that characterize transitional contexts.” We may assert as a matter of principle that societies ought to confront their pasts. We may advocate for such processes to take place. Yet we must proceed with the humble awareness that in such complex, emotional terrain, we cannot be certain whether or how a given process will help or hinder a developing society.

Only when the right conditions are joined by the right spirit can such a process succeed in helping a developing society to heal and move forward, thus fulfilling the words of Ezekiel’s prophecy: “Thus said the Lord God to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you and you shall live again.”

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.