I recently had the opportunity to visit Iceland, a jaw-droppingly magnificent place. Piles of volcanic rock, green and red mountains like huge hunks of bread littered around the landscape, glaciers, hot springs, plumes of steam rising from the earth, immense waterfalls cascading over cliffs — all of it entranced me. My sense of self seemed to shift. With my setting no longer the streets and buildings of New York City, but calderas and geysers and massive waves, I felt smaller — but not in a bad way. Rather, I felt lifted by elemental powers.

The feeling reminded me of the midrash that says: “The Torah was given through three things: fire, water and wilderness … Just as these are free to all the inhabitants of the world, so too are the words of Torah free to them. Anyone who does not make themselves ownerless as the wilderness cannot acquire wisdom and the Torah.” (Bamidbar Rabbah 1:7)

The nature of the wilderness, in this midrash, is that it is both hefker (ownerless) and chinam (freely accessible). This particular midrash does not assert, as other sources might, that God owns the wilderness, but rather that its spiritual essence is that it is not subject to the idea of ownership. The elements — water, air, earth, fire — are revelatory precisely because they are wild. The wilderness speaks (the Hebrew word for wilderness, midbar, means “place that speaks”) with a voice that is not merely an echo of our own. That is why wisdom is to be found there.

The Hebrew term for the elements is yesodot, literally “foundations”— the roots of the world. The elements are not only found in wilderness, they are, according to the Zohar, “the sources and roots of all things above and below.” Maimonides asserts that “all that comes from human or beast or bird or creeping thing or fish or plant or metal or precious stones or pearls or other building stones or mountains or earth-shapes, all of it, its form is shaped from the four elements.” The elemental exists in all things — once we know to look for it.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

As my family and I traveled through valleys and along seashores, I journeyed deeper and deeper into this sense of the elemental. The mingling of different forces made it impossible to neatly separate one substance from another. I couldn’t separate fire from water in the hot springs or water from earth and air in the fog on the moss. In my perception, the elements became a felt sense of creative force. “All the elements are one element,” the landscape seemed to be saying.

When I returned home, I searched for parallels to this idea and found an approximation of it in a statement from Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, who speaks of the yesod hapashut, the basic elemental. The idea comes from a verse in the Bible that reads: “The righteous is the foundation of the world.” The Zohar applies this verse to Noah and suggests that it means that the “world unfolds from him” — that is, his righteousness sustains the world. But Rebbe Nachman suggests something else. He offers the idea that the four elements all derive from one basic element embodied by the tzaddik, the spiritual master. He understands the foundation of the world mentioned in the biblical verse to refer to a kind of fifth element, the basic elemental.

Rebbe Nachman explains that because the tzaddik embodies this basic elemental, many students can see themselves reflected in the teacher. He further suggests that this quality also means that the teacher is always fundamentally and intimately connected to others. The righteous are thus able to channel blessing to all the diverse facets of reality.

What I hear in this teaching is that wisdom can be born from connection to the elemental, from experience of the vast, diverse and interconnected wildness in the world. Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg, the contemporary biblical commentator, seems to be saying something similar when she writes of the prophet Moses: “Perhaps this voice of the murmuring deep, inhuman, elemental, is what resounds in Moses’ voice.” The truly wise are able to speak in ways that somehow contain the wildness of the elemental and thus embody the connection we have to all things. And perhaps, the truly wise may be able to guide us to see the world as a wild entity with which we cooperate — but never truly own. If we cherish and respect the elemental, we may in so doing preserve ourselves.

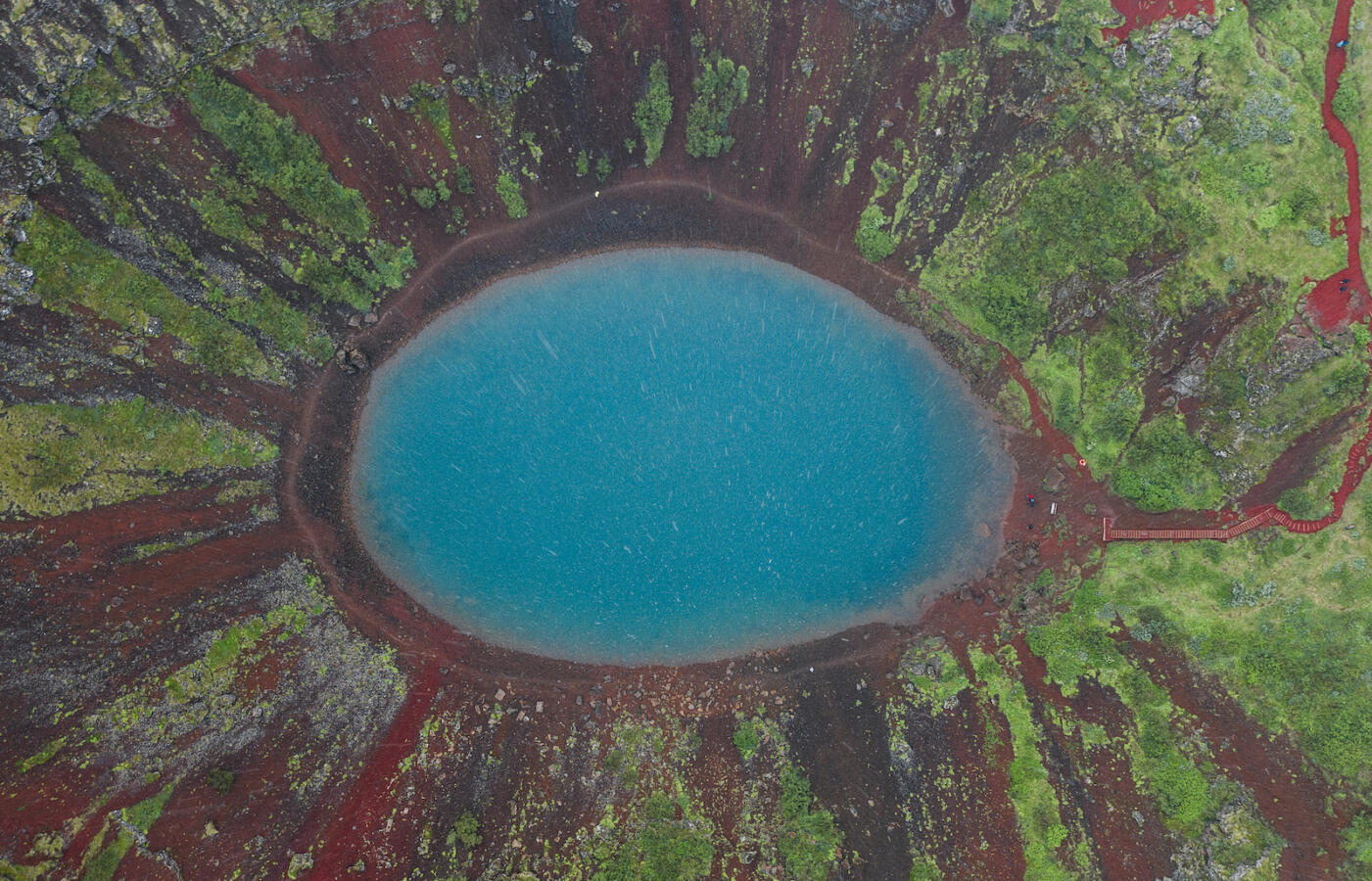

At one moment in my journey through Iceland, I looked down into the Kerid Crater, a perfectly round volcanic lake, and felt I saw the immense eye of the earth looking back at me. I hope I will always feel that sense of the earth’s aliveness. My prayer is that this memory and others like it will inspire me to feel even more deeply the yesod hapashut, the basic elemental, carried every day in the sunlight and the birdsong and the breeze lifting the leaves in Central Park. My prayer for all of us is that we may be worthy of being what the sages called yesod olam, a channel of elemental blessings for the world.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on July 30, 2022. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.