The practice of accompanying synagogue worship with music dates back to ancient times. The Bible recounts numerous occasions when song expressed thanks to God or enhanced Temple services. The Song of the Sea (Exodus 15) marked the occasion of the splitting of the Red Sea as the Hebrews escaped slavery in Egypt, and Deborah sang her song (Judges 5) to commemorate her defeat of the Canaanite general Sisera. King David’s musical skill as a lyre player (I Samuel 16) first drew King Saul to him eventually leading to his kingship; according to tradition, many of the 150 psalms in the canon of the Hebrew Bible were composed and sung by David.

David’s son Solomon built the first Temple in Jerusalem, and worship there included a large orchestra of harps, wind instruments, and voices, played and sung by members of the tribe of Levi. Psalms 120-134, the 15 “Songs of Ascents,” were recited regularly during ancient Temple service; each corresponded to one of the 15 steps the priest would climb to arrive at the altar.

David’s son Solomon built the first Temple in Jerusalem, and worship there included a large orchestra of harps, wind instruments, and voices, played and sung by members of the tribe of Levi. Psalms 120-134, the 15 “Songs of Ascents,” were recited regularly during ancient Temple service; each corresponded to one of the 15 steps the priest would climb to arrive at the altar.

With the dispersion of the Israelites following the destruction of the second Temple, the tradition of ancient Israelite music was lost. Today we may only speculate as to how this extensive repertoire of music sounded. But the practice of involving music in prayer endured. The fundamental components of synagogue music remain consistent throughout the world. Each community developed its own sound, often influenced by the music of its host region, and although those sounds are widely divergent from community to community, the basic structures of music in the synagogue have by and large remained constant. The musical components of the synagogue service are cantillation, nusah, hymns, and in some communities, niggunim.

Cantillation

Cantillation consists of the musical system for chanting texts from the Bible. The Pentateuch is generally read in short sections each Sabbath over the course of a year; various readings from the Prophets accompany the reading from the Pentateuch every week, and sections of the Writings are often read on special holidays. These sections of the Bible are read by one member of the congregation while the rest of the congregation listens.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The written notation for cantillation was developed by a group known as the Masoretes (from the Hebrew word Mesorah, meaning “tradition”), active as early as the sixth century, but who may have been recording much more ancient practices. The Masoretes inscribed each word in the Bible with a cantillation mark, indicating how it was to be sung. Those markings do not indicate specific notes or melodies, but only guidelines for enunciation. During the ensuing 1,500 years, each community’s cantillation melodies diverged and took on the character and sound of music of surrounding peoples, but the Masoretic markings and guidelines for cantillation have remained the same.

In addition to regional variances, communities often vary their cantillation melodies depending on the type of reading and the day on which the reading is done. For example, readings in the Pentateuch have different melodies from readings in the Prophets; a reading done on Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) sounds different from a reading done on an ordinary Sabbath. The most important element of cantillation is communication of the text. For that reason, there is no predetermined meter to any reading of the Bible; rather, the music must simply follow the flow and rhythm of the words.

Nusah

Nusah is a Hebrew word referring to a system of melodies used for chanting liturgy in the synagogue. The text of the siddur (prayerbook), contains elements that date back to Biblical times (for example, the psalms said during the morning and afternoon services), elements that were fixed by the sages who composed or are mentioned in the Talmud (for example, the Amidah, the silent prayer that is the centerpiece of every synagogue service), and elements that have been added much more recently (for example, poems such as Lekha Dodi (“Go, my Beloved,” sung on Friday nights to welcome the Sabbath).

Music makes a continuous whole out of these divergent elements. The cantor of a synagogue, or whoever serves as the sheliah tzibbur (messenger of the community, the term for a prayer leader), leads the congregation in chanting the appropriate texts of the prayerbook aloud. Nusah determines the melody of those prayers on a given day. The nusah of prayers on a weekday is different from that of a Sabbath or other holiday. As in the case of cantillation, the rhythm is quite free. Of primary concern is the natural flow of the text; the rhythm of the words determines the meter of the chant. Unlike in the system of cantillation, however, there is no musical notation to accompany the prayerbook. The cantor or leader must know the melody appropriate to the day and must be able to improvise the chant accordingly.

Cantorial Music

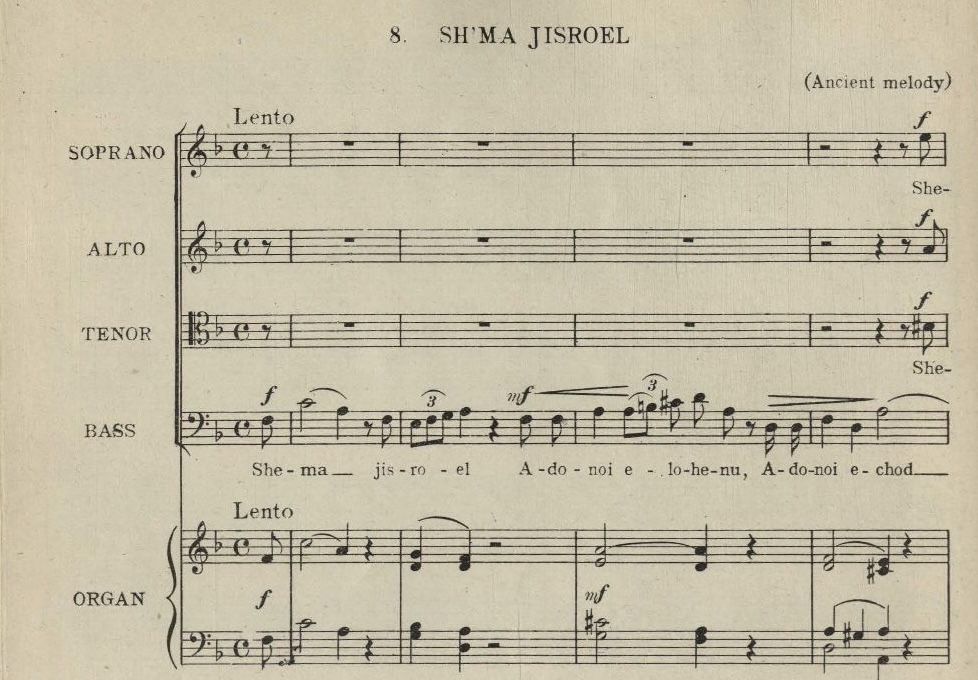

Many communities have professional cantors who lead the community regularly in prayer. This practice dates back several centuries, and it has led to the development of an extensive repertoire of cantorial music. Often written in the notational system of classical Western music, the cantorial repertoire represents an element of virtuosity and soloism. Professional cantors are especially important in cases where the majority of the congregation does not know the words or nusah of prayer, but many congregations find that a cantor with a beautiful voice may enhance the synagogue experience. The technology of recording in the last few generations allows us to hear voices of great cantors such as Jan Peerce (also a prominent opera singer), Israel Alter, and Yossele Rosenblatt.

Prayerbook Poetry

Hymns and poetry constitute a subsection of the prayerbook. As early as the fifth century, Jewish poets composed piyyutim, poetry intended to enhance the prayer service. These piyyutim, as well as the more recent hymns and songs inserted into the prayer service, possess a regular poetic meter. For that reason, hymns and piyyutim often lend themselves to more regularly metered musical settings.

Commonly recited hymns–including Adon Olam (“Master of the World,” often sung to close services on Sabbath mornings) and Lekha Dodi–may be sung because of their regular meter to common Jewish melodies, or even to popular tunes from the surrounding musical environment.

Niggunim

Niggunim are musical settings of a few words or short phrases in Hebrew or Yiddish–which are repeated over and over again in order to attain a deep understanding of the text or in order to attain a sort of spiritual “nirvana.” Depending on the meaning of the text and the intention of the composer, niggunimmay be fast and joyful or slow and intense.

Originally composed and inserted into the prayer service by members of the movement of Hasidut (from the Hebrew hesed, meaning “kindness”), niggunim were meant to elevate the experience of prayer and to make that elevated experience attainable by any Jew. It is that populist element of Hasidut that encouraged the melodies of niggunim to be relatively simple and repetitive. Often, the words of the niggunim were omitted in favor of humming or syllabic singing.

The practice of singing niggunim was popularized beyond the boundaries of Hasidut in the late 20th century by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, who composed and recorded hundreds of them. Today, niggunim may be heard as part of synagogue services as well as outside the context of prayer at celebrations and lifecycle events.

Rosh Hashanah

Pronounced: roshe hah-SHAH-nah, also roshe ha-shah-NAH, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish new year.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.