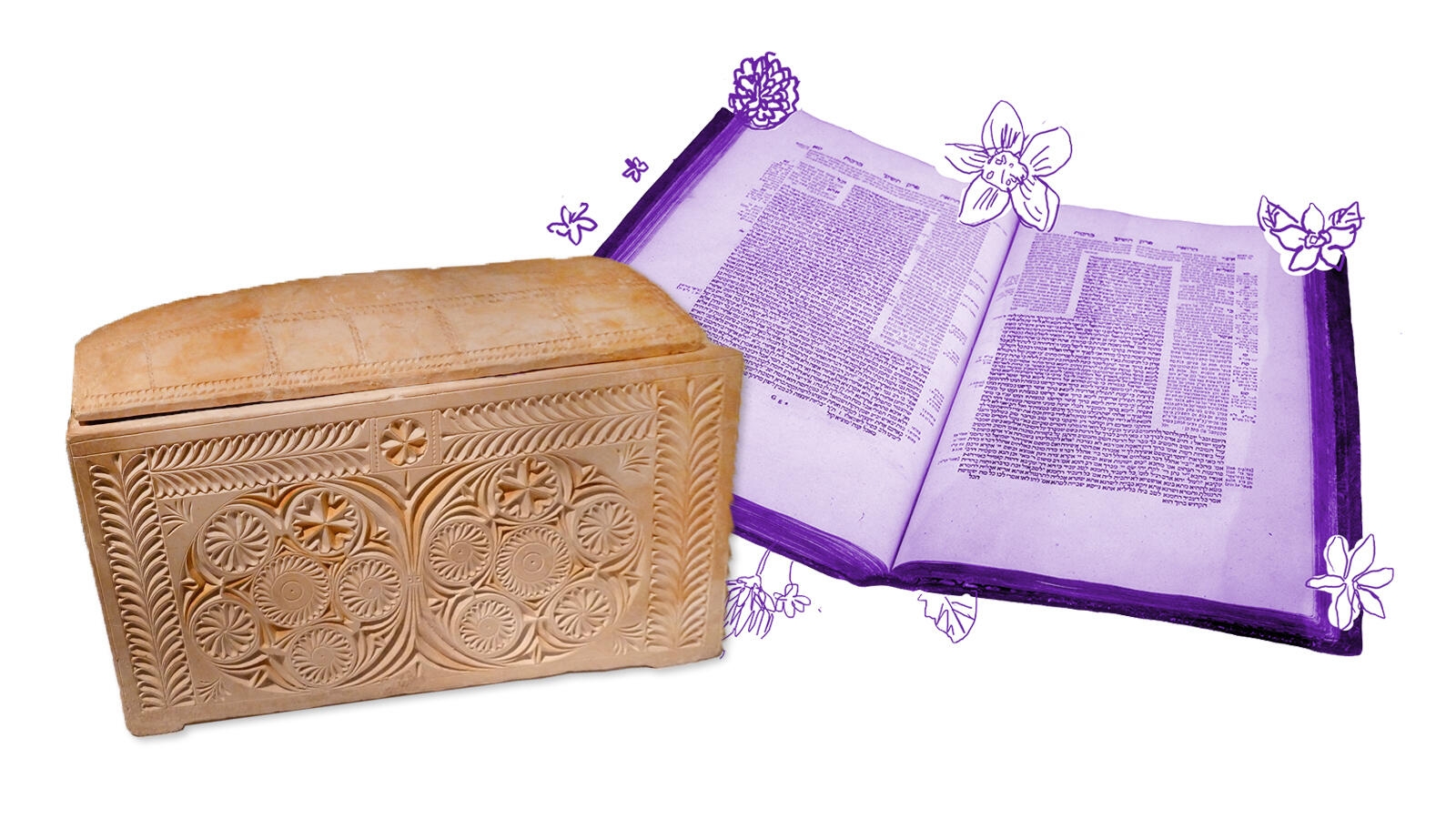

Moed Katan is a short tractate (just 29 pages) that largely concerns the laws governing the intermediate days of the weeklong festivals of Passover and Sukkot (hol hamoed). These days do not have the same requirements as the beginning and end of the festivals, during which time no work may be performed save that required to cook the festival meals, but they are not like regular days on which all labor is permitted. The last portion of the tractate pivots to a discussion of the laws of mourning.

Chapter 1

This chapter is devoted to a discussion of which labors are permitted on hol hamoed and which are forbidden. In the opening mishnah, there is an analogy to the agricultural laws of the shmita (sabbatical) year. The underlying principle is that festivals are sacred occasions and should not be treated like ordinary work days, and onerous work that would ruin the experience of the festival is best avoided. At the same time, in a largely agrarian society, workers cannot neglect their fields during these pivotal times of year and certain kinds of labor that are not too onerous and/or are designed to prevent major financial loss are permitted. But difficult labors, especially those designed to significantly improve profits over what would normally be expected, are forbidden. The reason, at least in part, is to maintain the joy of the festival. The joy of the festival is also cited as the reason that priests do not examine people for tzaraat (leprosy) — so that they are not declared lepers during the joyous time of the festival. It is also ruled that one may not eulogize the dead during these days, which would dampen the joy of the festival, or get married, a celebration that would compete with the joy of the festival.

Chapter 2

This chapter continues the discussion about which labors are forbidden and which are permitted on the intermediate days of a festival. The sages determine that labor is permitted to prevent financial loss — even a small one. In addition, people may prepare meals (which, as we learned in Tractate Beitzah, is permitted even on the first and final days of the festivals), purchase food for the festival and even work to earn the money that will be used to purchase special food for the festival. Likewise, stores may open to sell food during this week, even food that is shelf stable and would not necessarily expire before the end of the festival. It is also permitted to perform labors that benefit the community during hol hamoed, though labors designed to simply enrich oneself are still forbidden.

Chapter 3

This chapter opens with a ruling that one whose circumstances did not allow them to “freshen up” ahead of the festival — enjoy a bath and a haircut — may do so on the intermediate days of the festival.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The mention of those who are unable to obtain a haircut before the festival naturally leads into a discussion of those who are excommunicated or those who are just ostracized, a more lenient and temporary form of excommunication usually imposed on rabbis who refuse to accept majority rulings. The laws that attend both kinds of social isolation are discussed.

The latter part of this chapter is devoted to the halakhot of mourning. Here we find rules about eulogizing, kria (tearing one’s clothes as a sign of mourning), meals made to comfort mourners, learning Torah while mourning, degrees of mourning, length of mourning, and the rules for mourning a death that took place a long time ago but which one has only recently learned of.