When most people hear the name Samson, they think of Delilah, his treacherous paramour who discovers the source of his superhuman strength and then robs him of it. But there is a lot more to the biblical Samson — and to the women associated with him — than Delilah.

Samson is the final judge in the Book of Judges, which describes the leaders of Israel after the death of Joshua, Moses’s successor, and before the monarchy, beginning with Kings Saul and David. “Judges” is a poor translation of the Hebrew word shoftim, which in this context refers to local military leaders. They are presented in order of best to worst, culminating with Samson. Biblical leaders do not always present positive examples to emulate, and Samson certainly falls in this category. Born with supernatural strength and an obligation to God and his people, Samson spends most of his short life carousing and inciting violence.

Judges 13–16 presents Samson’s life in several disjoined episodes of different lengths and styles: the first chapter describes his miraculous birth; the last verses, his tragic death. The first woman associated with him, not surprisingly, was his mother, who like many biblical female figures is unnamed. After much difficulty having children, an angel comes to give her the good news that she will bear a son. Reading between the lines, the text suggests that this angel is in fact his real father; a colloquial translation of Judges 13:6 is: “The man of God came on to me, and he looked like an angel of God, super-awesome!” His father’s divinity is one of the story’s explanations of Samson’s great strength, a theme that runs throughout the chapter. In fact, the name Samson, in Hebrew Shimson, derives from shemesh, “sun,” suggesting an original connection between Samson and the sun god.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Samson’s next woman is a love interest, an unnamed Philistine from Timnah. Like some contemporary Jewish parents, Samson’s are upset that he is going with a foreign girl, though the text makes it clear that “his father and mother did not realize that this was the Lord’s doing: He was seeking a pretext against the Philistines, for the Philistines were ruling over Israel at that time” (14:4). Why would Samson’s relationship to a Philistine woman be an occasion for God hobble the Philistines, who were oppressing Israel? It’s nearly a chapter before we’re able to understand this claim in the text. Here’s how it happens: At his wedding with the unnamed Philistine woman, Samson bets the Philistine guests a considerable sum that they will not be able to answer a very difficult riddle. When, several days into the wedding feast, they still cannot figure it out, they wrest the answer from his bride. When they approach Samson with the correct answer, Samson immediately assumes they have slept with his new wife in order to learn it. In a fury, he kills 30 Philistines and steals their possessions to pay his debt. Then, still full of rage, he abandons his new wife and goes home.

When Samson finally returns in a later season with a goat as a gift, he finds that his wife has married someone else, and her father offers up her younger sister as a substitute. Samson flies back into a rage and declares, “Now the Philistines can have no claim against me for the harm I shall do them” (15:3). He attaches lit torches to the tales of foxes and sets them to run through the Philistine fields, burning the crops. This illustrates how God used Samson’s marriage to set in motion a series of events that weakened the hold of the Philistines over Israel.

The theme that God works in most unexpected ways is carried throughout the Samson stories — as is the theme of his appetite for sex and violence. For two chapters (14 and 15), Samson gets into various misadventures that ultimately involve killing Philistines — the more the merrier, and the more absurd the method, the more amusing. He is strong in these stories only when “the spirit of the Lord alight[s] upon him.” And God even performs miracles for him, splitting open a rock and creating a fountain when he is about to die of thirst after smiting one thousand Philistines with the jawbone of a donkey. That latter episode ends with the notice, “He led Israel in the days of the Philistines for twenty years,” suggesting that the story once ended there.

But more legends circulated about Samson, and some of these found their way into Judges. The next, very brief one tells how Samson was ambushed while visiting another woman — an unnamed prostitute in Gaza — and escaped by carrying off the city gates (16:1–3). Here he does not need to wait until “the spirit of the Lord alight[s] upon him,” but is naturally super-strong.

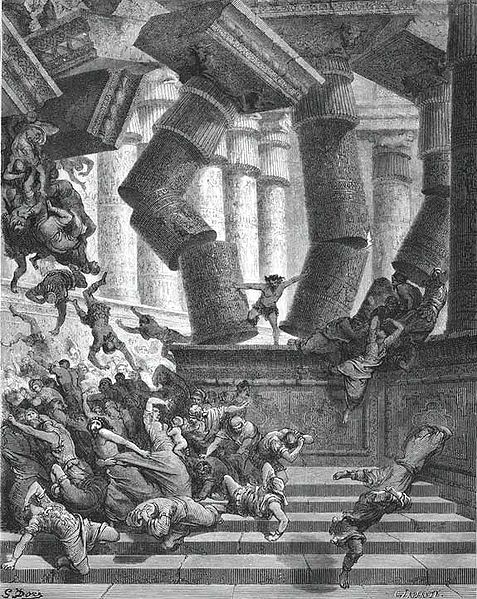

This brings us to the last story — about Samson’s fourth woman, who is finally named, Delilah, a word that may be etymologically related to the word for “hair.” This story assumes that Samson is strong due to the hair he has grown in fulfillment of the Nazirite vow imposed on his mother by the angel, and once his hair is shorn, he loses power. Although she proves herself a treacherous lover who attempts to have him killed at every opportunity, Samson, worn down by Delilah, confides in her that his hair is the secret of his strength. She immediately lulls him to sleep, shaves his head, and arranges for his capture. The Philistines who gladly imprison him gouge out his eyes. Blinded by his enemies and unable to return to the life of a carousing strongman and protector of Israel against the Philistines, Samson begs God to return his strength just long enough to topple a Philistine palace, killing himself and three thousand Philistines on its roof.

What are we to make of Samson? Some readers may see similarities to the Greek Heracles/Hercules, and for over a century scholars have suggested that these myths have influenced the Bible here. The Philistines, like the Greeks, came from the Aegean, and may have been sharing Heraclean stories with the Israelites. But the current story turns these myths on their head: instead of celebrating a Greek demi-god, they mock the Greek-related Philistines.

It is hard to put together the different images of Samson, especially concerning the source of his strength: from his divine father, from his hair, or from the spirit of the Lord? This suggests that we do not have a unified Samson story, but a cycle, a group of loosely connected episodes of diverse origin. The composite nature of these four chapters is buttressed by the double ending of the story, with both 15:20 and 16:31 noting that he judged Israel for 20 years — a story-ending formula in Judges as recognizable as “they lived happily ever after.”

An ancient synagogue mosaic showing Samson smiting the Philistines with a donkey’s jawbone shows how positively he was viewed by some in late antiquity — probably as an emblem of the powerful Jew, created at a time when Christianity was starting to dominate Palestine. The rabbis, who emphasized learning and religious observance over might, were quite ambivalent about Samson. While they praise his unselfish nature and exaggerate even more his heroic killing of Philistines, they also condemn his wandering eyes, which got him entangled with the women who led to his downfall. Invoking one of their favorite principles, measure for measure, they note: “Samson followed his eyes, and that is why the Philistines blinded him.” For the rabbis a fun story, a transformation of Greek hero tales, must always have a lesson.

Want to get to know more amazing, complicated, and relatable biblical personalities? Sign up for a special email series here.