In 1987, when Joel Hornstein stood before more than 200 congregants, family members, and friends to recite his bar mitzvah Torah portion in English and Hebrew, he had only been able to speak for a few years. No one expected a child with autism, or any other significant disability, to undertake the rigorous training in a foreign language needed to prepare for this significant Jewish rite of passage. Jewish special education was almost nonexistent.

Yet Joel’s family wanted to provide him with the opportunity to declare his value and dignity before God and their community, and celebrate his journey out of the solitude of autism.

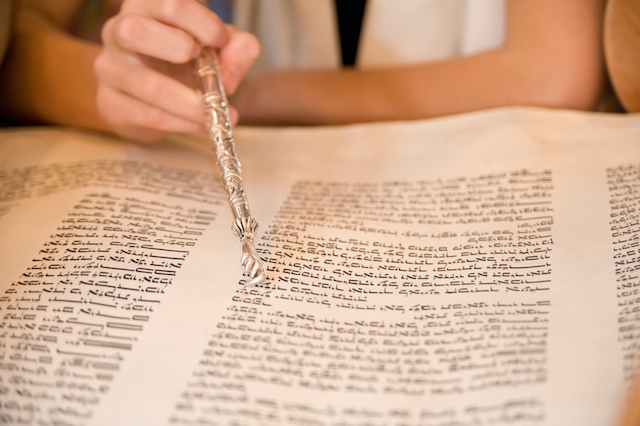

In the years since Joel’s bar mitzvah, increasing numbers of Jewish children with disabilities have sought to prepare for similar celebrations. A bar or bat mitzvah is a milestone in a person’s development as a Jew. A public celebration of reaching the age of Jewish majority, it indicates the acquisition of a certain amount of Jewish knowledge as well as interest in ongoing participation in Jewish life.

People with severe disabilities may not have acquired formal learning at a level comparable to those without disabilities, nor may they have the ability to make an ongoing commitment to education. However, they do recognize their emotional and psychic ties to the Jewish people and wish to participate in the community to the best of their ability.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Misconceptions, even prejudices, about people with disabilities linger. Some people question whether a child with a severe disability can and should have a bar or bat mitzvah ceremony. They may doubt that such a person can sustain the desire to become a bar or bat mitzvah. They may harbor rigid ideas of what the ritual entails, and may not be willing to adapt the ceremony to the needs and abilities of the person. They may not know that other people with comparable disabilities have had similar celebrations.

Family members of people with disabilities may hesitate to broach the subject for fear of rejection, or they may even be unaware of the possibilities that could be open to their loved one. Sometimes, however, people with disabilities are welcomed, and the discussion centers on how to make such an event happen.

Cooperation and Careful Planning Are Critical

Planning is the key to the success of any bar or bat mitzvah ceremony; accommodating a person with disabilities requires preparation well beyond the usual. Patience, energy, commitment, and cooperation among parents, the rabbi, cantor, and religious school teacher, and whenever possible, the person with disabilities is essential. They should consider themselves a team with one goal in mind: the development of a beautiful and meaningful ceremony that recognizes the person with a disability as a member of the Jewish community and is an affirmation of Jewish life that transcends all the usual boundaries.

Basic questions about the child, the family, the synagogue, and the professionals involved must be thoroughly discussed and resolved to everyone’s satisfaction at the outset. Starting far in advance of the target date, the team should agree on comfortable and achievable goals and a plan of action. Open, honest dialogue can prevent misunderstandings and facilitate the process.

Focus on Child’s Strengths, Weaknesses, and Unique Gifts

Discussion should begin by realistically acknowledging the young person’s strengths and limitations. All future plans can then follow in a way that maximizes his or her abilities and circumvents possible problems. An honest assessment of what is educationally and behaviorally possible for the child is essential to guide the team in designing an appropriate and meaningful experience. The focus should be both on the ceremony itself and on the preparation for it.

People learn in different ways, and preparation should be completely individualized and incorporate this child’s strongest modalities. What can he or she realistically learn and how is that learning best accomplished? Are audio or video tapes helpful? Can material be color-coded or written in large print? Parents and Jewish educators may want to consult with secular educators who may be able to be very specific in pinpointing how the child learns best and how he or she will best be able to demonstrate those accomplishments.

People who have disabilities also have unique gifts, which should be reflected in the ceremony. Preparation should consider ways to express this person’s talents and feelings about Judaism and its significance in his or her life. Does he or she have a particular love for music or dance? Can he or she paint or draw an interpretation of the Torah portion? With a goal of helping a person with disabilities feel accepted and comfortable, highlighting his or her special gifts can provide the mechanism for celebrating his or her Jewish identity. For example, one bat mitzvah girl, who is an elective mute, displayed an original painting that expressed her feelings about her Torah portion.

Modify Format of Ceremony

Once these questions have been answered, the family should determine their goal for the event. What will make it meaningful to each of them? What will make this a “real” bar or bat mitzvah for them? Who should participate and how? Who should be there to share the experience?

The cooperation of the synagogue’s professionals is critical to a successful experience. Must all bar/bat mitzvah ceremonies follow the same formula in order to be acceptable? Can the ceremony be shortened, individualized, or carried out in a completely unique manner? How willing are the professionals to help plan and expedite such a service? How supportive will the congregation be of a ceremony that is different from the usual?

The ceremony itself should be designed to take advantage of the child’s strengths and, as much as possible, to avoid problems. How predictable is this person’s behavior? What will make him or her comfortable or uncomfortable?

Preparation that is site specific can be very helpful on the big day. Decide where the service will be held and try to practice in that environment. Perhaps the synagogue is not the optimal place; the person’s home or a room at his or her school may be more comfortable and less distracting. Wherever the ceremony will be held, it is helpful to schedule some teaching sessions at the site so that the ceremony will not take place in an unfamiliar and, therefore, overwhelming environment.

Some children will manage better if the ceremony is as brief as possible, and does not coincide with a regular congregational service or other communal event. Then, the rabbi can stop or modify the service if the child becomes overstimulated or anxious. One rabbi, knowing that a young man’s attention span was approximately 15 minutes long, was prepared to finish the ceremony quickly and announce to the assembled guests that it was wonderful that they had been able to celebrate together.

The team should also identify specific stimuli that distract or overstimulate the child and plan to accommodate them. Are specific sounds upsetting? Are crowds too stimulating? Does making eye contact upset the person? The child could face away from the congregation to avoid being frightened or overstimulated by eye contact with the crowd. Are certain articles of clothing irritating? This child should wear comfortable and familiar clothing, not something new, stiff, and uncomfortable. Does the person need to stand or walk between prayers? Does he or she need to sit throughout the ceremony because alternating standing and sitting is overwhelming? Aware that one bar mitzvah boy might wander throughout the sanctuary, the rabbi explained to the congregation that the entire room was the bimah [pulpit] that day. If the people planning the ceremony can answer questions like these in advance and take the appropriate steps to make the person with disabilities feel comfortable and relaxed, the day will prove much more successful and pleasant for everyone.

The ultimate success of such a ceremony is a triumph, not only for the individuals involved, but for the entire Jewish community. The bar or bat mitzvah of a young person with a disability demonstrates vividly what Judaism is, or should be, about. The challenges are not insurmountable; it only takes the willingness to plan ahead, flexibility, and creativity. In this way, we can truly “educate each child according to his or her ability,” and fulfill our obligation to provide a Jewish education for every child.

For more thoughts and insights about planning a bar/bat mitzvah for someone with special needs you may want to watch the film Praying with Lior about a boy with special needs and his family planning his bar mitzvah.

Reprinted with permission from JewishFamily.com.

bar mitzvah

Pronounced: bar MITZ-vuh, also bar meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish rite of passage for a 13-year-old boy.

bat mitzvah

Pronounced: baht MITZ-vuh, also bahs MITZ-vuh and baht meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish rite of passage for a girl, observed at age 12 or 13.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.