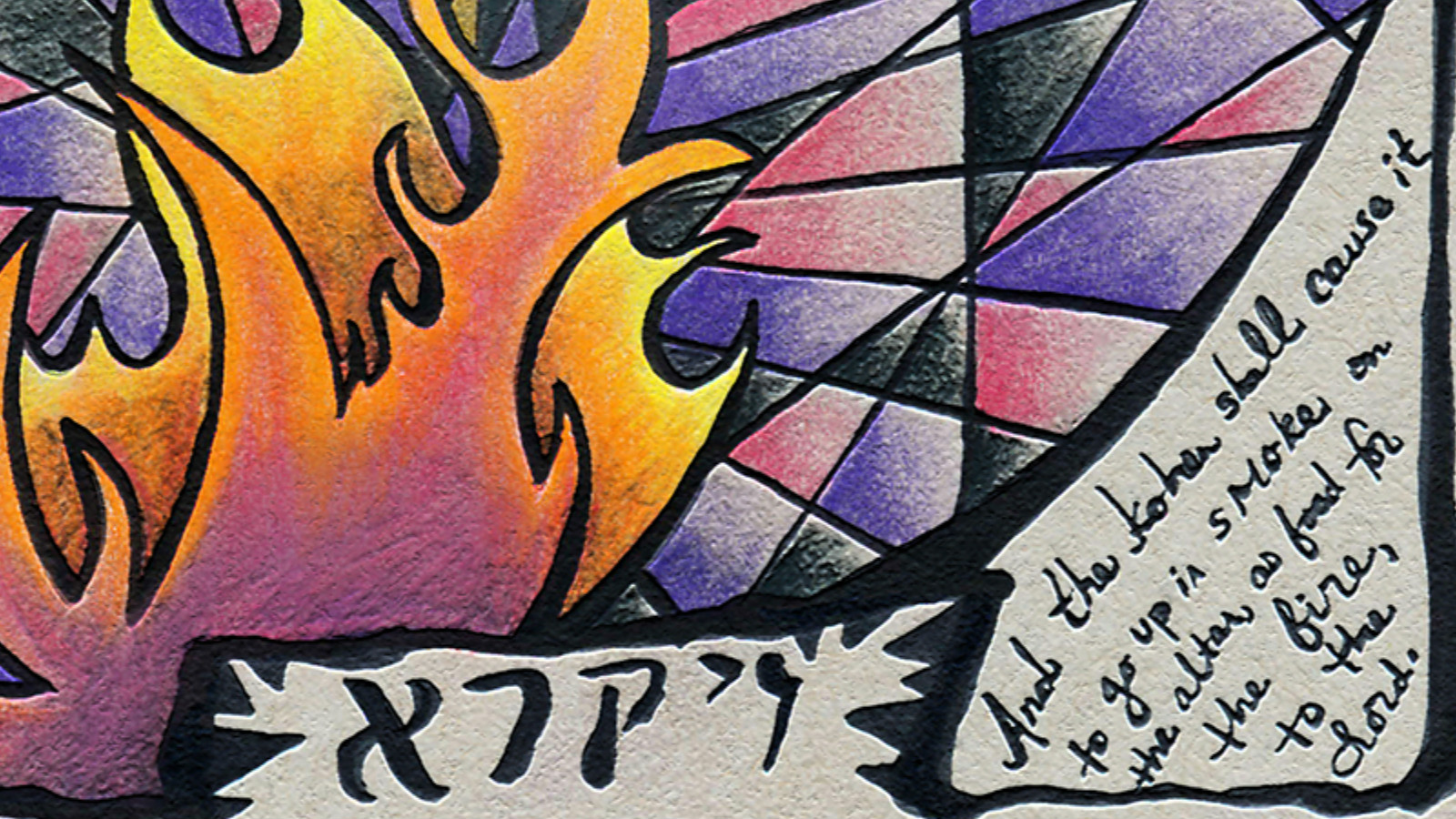

Commentary on Parashat Vayikra, Leviticus 1:1-5:26

The book of Vayikra preoccupies itself with korbanot, what today we might describe as the peculiarities of ritual sacrifice: which types of animals should be sacrificed, where they should be offered, what accompaniments should be presented alongside them and how and when they should be presented.

The nature of sacrifice as we understand it has shifted dramatically in the last 2,000 years. We have no temple and no animal sacrifices, so what then are we meant to learn from korbanot? Why need we concern ourselves with the details of sacrificial law?

Let’s begin with the word itself. In Latin, sacrifice finds its root in two words: sacer, meaning sacred rites traditionally performed by priests, and the verb facere, meaning to place something. The implication is that sacrifice is the act of making something sacred by setting it aside for a specific religious purpose. In Hebrew, this is more often the translation associated with the word kadosh, or holy. We see this later on in the book of Leviticus, when we are commanded kedoshim tihiyu: be holy. The commentator Rashi explains this command as telling us to be separate and keep distance from illicit sexual relationships. In both words, sacrifice and kadosh, there is an implicit distance between that which we wish to designate as holy and all other things. This distance could be either physical or metaphysical. Shabbat, for example, becomes imbued with holiness by setting it aside from the remaining days of the week.

The act of bringing sacrifices doesn’t create distance and separateness in the way that the word might normally imply. Rather it requires closeness. The individual must be at a certain location and must offer the animal in a certain way. It is very much a hands-on activity. The word korban itself comes from the Hebrew root meaning close. The korban not only requires closeness, but can also be said to engender closeness between the giver and God.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler notes that the way one grows their love for another or for God is by giving unconditionally. One might think that what makes us love another person is all the wonderful things they do for us and that our love grows as those individuals continue to grow in their devotion to us. In fact, Rabbi Dessler asserts the opposite. Relationships become more powerful when we give to them unconditionally without expectation of return. This constant giving creates a sense of buy-in or connectedness to that which you have given, and engenders an investment on the part of the giver which in turn initiates more giving. Giving begets loving which in turn begets giving. This is probably most apparent with parents and children. Parents give unconditionally before they ever get anything in return.

The act of korbanot is teaching us this very lesson. Korbanot are about creating closeness; closeness with God and closeness with community. The korban creates a paradigm for how to build, connect and deepen devotion. It is the opposite of sacrifice, which puts things aside and designates them as separate. Korbanot are about connecting and giving unconditionally.

When we read the Torah portion of Vayikra, we can hear the message of the korbanot calling us to the message of closeness and connectedness with others. We can use this time to think about what we can each be giving unconditionally to those around us and to the community so that we can continually build a more cohesive society.

Read this Torah portion, Leviticus 1:1 – 5:26 on Sefaria

Sign up for our “Guide to Torah Study” email series and we’ll guide you through everything you need to know, from explanations of the major texts to commentaries to learning methods and more.

Subscribe to A Daily Dose of Talmud: Daf Yomi for Everyone — every day, you’ll receive an email that offers an insight from each page of the current tractate of the Talmud. Join us!

About the Author: Anat Barber is an alumna of the Ruskay Institute for Jewish Leadership and the Wexner Graduate Fellowship Program and completed a dual degree program in Jewish studies and Public Service at NYU. Anat is currently the assistant director of capital gifts and special initiatives at UJA-Federation of New York.