Commentary on Parashat Tazria-Metzora, Leviticus 12:1-15:33

The fourth and fifth Torah portions in Leviticus, Tazria and Metzora, focus on naturally occurring physical phenomena that put a person in a temporary state of tumah, or ritual impurity, which precludes them from approaching God’s sanctuary. These include contact with any bodily emission that relates the generation of life (such as semen or menstrual blood) or the affliction of tzara’at, a range of skin infections akin to leprosy, though much more complex. Tzara’at not only puts one in a state of tumah, it also forces one to be isolated from human contact until the skin infection has healed.

We can assume this information is presented at this point because in the previous Torah portion, the newly built desert Tabernacle has finally been dedicated and is open for business, so people need to know when they are not suitable to present an offering to God. Harder to understand is why the Torah devotes two lengthy chapters to such hyper-focused detail about the spectrum of dermal infections and the priestly role as healer.

This has baffled rabbinic commentators through the millennia. Many of the classic commentaries understood this level of detail to suggest that there is a direct relationship between our spiritual state and our physical presentation. One of the best-known allegorical interpretations notes the aural similarity between the word for leper (metzora) and the act of gossip (motzi shem ra), suggesting that one’s outer bodily decay could be punishment for the sins of slander and malicious speech. These early rabbinic insights were prescient, reinforced by what we now understand about the mind-body connection with respect to overall physical health.

The rabbis agree that the highly detailed isolation and purification regimens were driven by a compulsion to protect the uninfected from contracting the disease, regardless of how or why the carrier contracted their contagion. In Leviticus 13: 45-46 we read:

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

As for the person with a leprous affection, his clothes shall be rent, his head shall be left bare, and he shall cover over his upper lip … He shall be impure as long as the disease is on him. Being impure, he shall dwell apart; his dwelling shall be outside the camp.

The 13th-century rabbinic authority, Rabbi Jacob ben Asher, suggested that the mandate to “cover over his upper lip” meant that the leper would need to cover her mouth to avoid infecting others with her breath, an insight that predates the discovery of airborne illness by several centuries.

The experience of having lived through a pandemic allows us appreciate these details in a new light. Mandated isolation and covering our mouths to protect others from becoming ill now has startling new relevance. And just as tzara’at was manifest in many forms of skin disease, COVID-19 impacted people in different ways. Like the leper relegated to living alone outside the camp, we all understand the need for some kind of isolation to limit the spread of disease. And like the priests, front line health care workers acted as God’s agents in providing diagnosis, treatment and nursing.

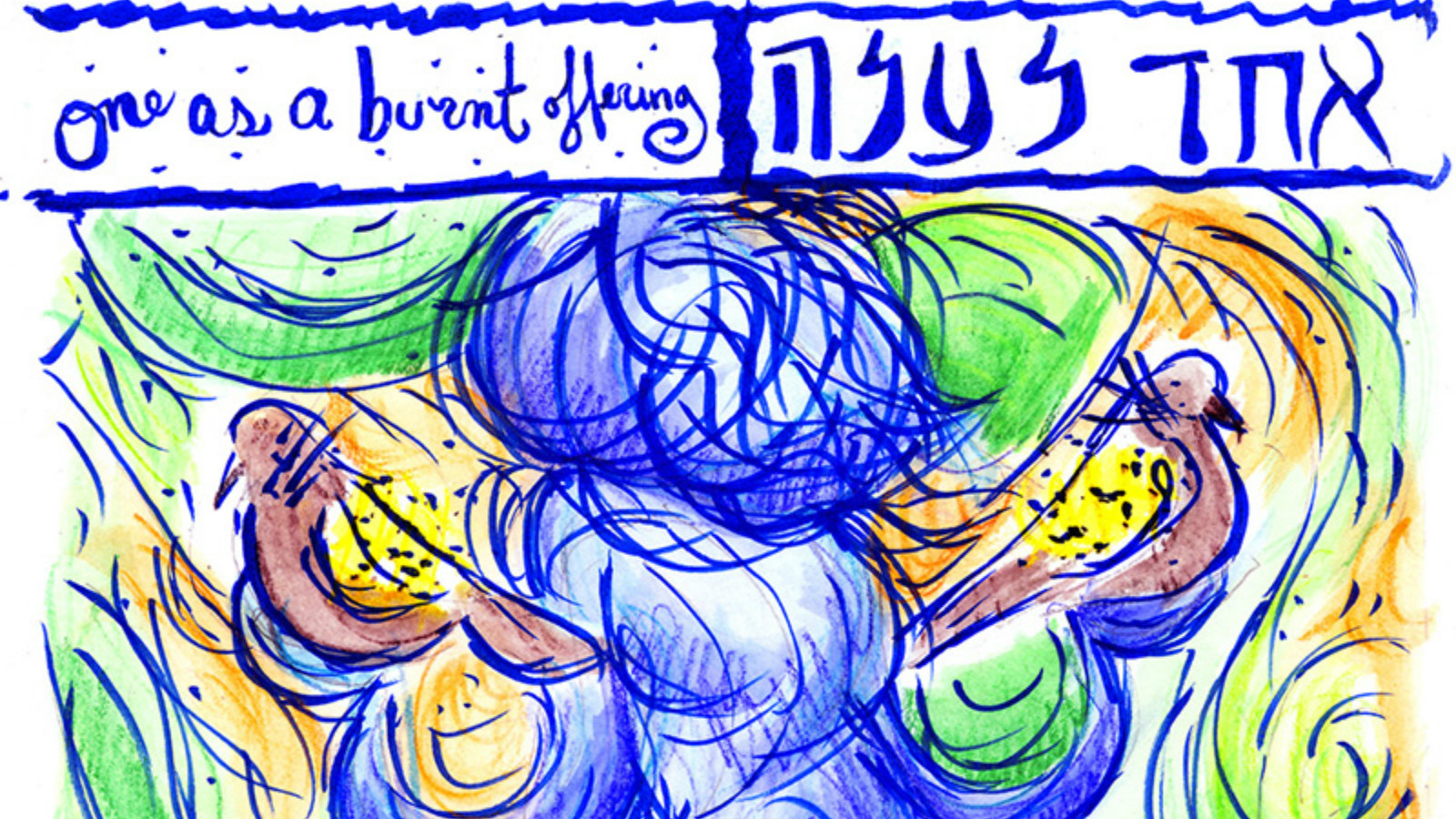

These Torah portions also tell us something important about re-entering society after the forced isolation necessitated by illness. They prescribe a complex ceremonial ritual for the healed leper that involves two birds, cedar wood, crimson stuff and hyssop. As part of the ceremony, one of the birds is killed and the other is dipped in its blood before it is set free, forever marked by what was lost and changed during the period of sickness. Eight days later, the healed leper must bring both a purification and reparation offering before God.

Like the freed bird, no one is left unscarred by the coronavirus pandemic. The choice is ours to decide how we offer thanks for what we have learned through the process. We now have the tools to mitigate the chronic loneliness and isolation of others through consistent virtual connection. We can each continue to consciously reduce our carbon footprint as much as possible to expedite the protocols for planetary survival. Most of all, we now see that every person is a member of one global human family in which the actions of one can and will impact the lives of hundreds, for good and for harm. May we all understand the import of this holy responsibility and choose to partner with God as protectors and healers.