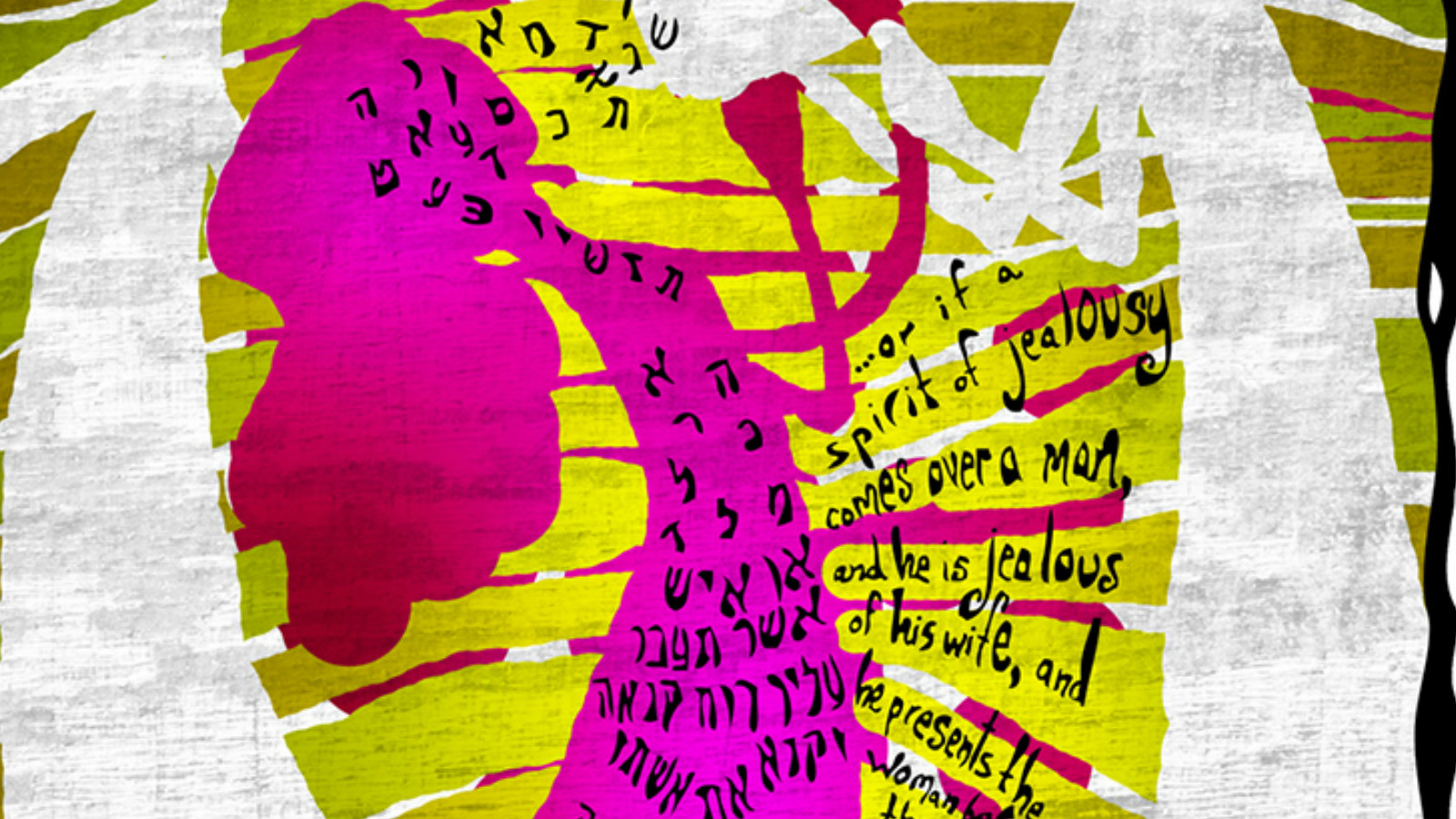

Commentary on Parashat Nasso, Numbers 4:21-7:89

After providing details about how the Israelites organized their encampment during their travels in the desert, the Torah turns its attention in Parashat Nasso to the gifts that were brought by tribal chieftains for use in the Tabernacle:

On the day that Moses finished setting up the Tabernacle, he anointed and consecrated it and all its furnishings, as well as the altar and its utensils. When he had anointed and consecrated them, the chieftains of Israel, the heads of ancestral houses, namely, the chieftains of the tribes … drew near and brought their offering before the Lord (Numbers 7:1-3).

The construction of the Tabernacle and its dedication have been a central theme of the biblical narrative beginning in the second half of the book of Exodus, continuing into the book of Leviticus, and concluding in the book of Numbers. The task engaged many people.

The Israelites were commanded by God to donate the materials that would be used to build and equip the Tabernacle. The Torah reports that their response was overwhelming, so much so that the people were told to stop giving as the sheer quantity of the materials that had been donated had become a burden to the project managers.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

So given the widespread involvement in the Tabernacle project, why would the Torah choose to open its narrative with the words, “On the day that Moses finished setting up the Tabernacle”? In doing so, it appears that credit is being given to Moses for a project that was a group effort.

The medieval commentator Rashi suggests that the Torah does this “because Moses devoted himself wholeheartedly to it, ensuring that the shape of each article was exactly as God had shown him on the mountain and showing the workmen how it should be made — and he did not err on a single shape.”

In other words, in giving credit to Moses, the Torah is not ignoring the contributions of others, but rather recognizing Moses’ unique leadership, passion and dedication for the project and his efforts to ensure that it was completed exactly as God had envisioned.

Just a few verses later, while describing the gifts brought to the Tabernacle by the heads of each of the tribes, the Torah fails to identify Nachshon Ben Aminadav as the chief of his tribe as he brings the first gift. This is noteworthy, as the Torah takes the time to describe each chieftain’s gift individually, even though they are all identical, emphasizing their equal status. Why would the Torah present Nachshon differently from his peers?

One could say that in dropping his title, the Torah is not slighting Nachshon; rather, it is honoring him for bringing humility to his position. Perhaps while serving as chieftain of his tribe, Nachshon never held himself above those he represented, and unlike his peers, he did not let the status of his position go to his head. Thus, what appears to be a slight is actually a compliment.

The Midrash has a different theory. It suggests that the reason Nachshon is not called by his title is so that “if he should ever feel tempted to lord it over the other chieftains by saying, ‘I am your king, since I was first to present the offering,’ they could retort by saying, ‘You are no more than a commoner, for every one of the others is called a chieftain, while you are not described as one.’”

Sometimes, people in positions of authority need to be reminded not to overstep. Yet couldn’t the message that bringing the first gift did not mean that Nachshon was first among equals have been delivered without slighting him? Likewise, couldn’t the Torah have found a way to recognize Moses for his leadership alongside others whose contributions are worthy of recognition?

Thinking about Parashat Nasso, it’s hard not to think about the need to speak sensitively, to find ways to praise someone without slighting others, and to honor the contributions of every individual without diminishing those of their peers. Doing so strengthens our ties to one another and helps ensure that God’s presence will reside in the sacred spaces that lie in the heart of our encampments.

Read this Torah portion, Numbers 4:21 – 7:89 on Sefaria

Sign up for our “Guide to Torah Study” email series and we’ll guide you through everything you need to know, from explanations of the major texts to commentaries to learning methods and more.

Subscribe to A Daily Dose of Talmud: Daf Yomi for Everyone — every day, you’ll receive an email that offers an insight from each page of the current tractate of the Talmud. Join us!

About the Author: Rabbi Elliot Goldberg is a teacher, curriculum consultant, teacher trainer, and professional coach with more than two decades of experience in Jewish day schools and a lifetime of summers at Ramah Camps. He has a passion for studying Jewish texts with teens and adults and is learning Daf Yomi for the first time this cycle.