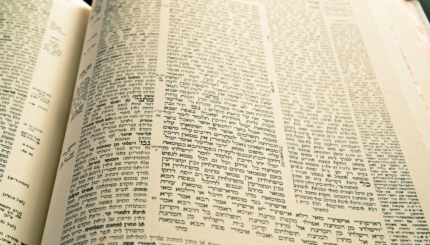

The feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s caused women to question their roles in the family, in the workplace, in society at large, and in religion. Orthodox Jewish women were no exception. It was in this social context that, in the late 1970s, institutions began emerging in Israel and the United States that offered advanced text-based Jewish learning–including the study of Talmud–for Orthodox women. These institutions, like Matan in Jerusalem and Drisha in New York City, created a cadre of learned Orthodox women who wanted to take on public roles in religious life.

Though these women have not been given the title “rabbi”–the Orthodox rabbinate remains all-male–some Orthodox women have assumed para-rabbinic roles in their communities. Working as rabbinical advocates, family purity experts, and synagogue leaders, these women perform tasks that were once exclusively the domain of male Orthodox rabbis.

To’anot

In Israel, since the early 1990s, women have functioned as rabbinical advocates, or to’anot rabaniyot. Prior to 1990, this was a job that was performed only by male rabbis (to’anim). The task of an advocate–male or female–is to help divorcing couples navigate the tricky Jewish legal system. Since there is no civil marriage or divorce in Israel, any couple wishing to divorce must follow the proceedings of a beit din, or rabbinical court, where secular legal

representation is supplemented by halakhically trained and certified advocates familiar with the complex rabbinical law involved.

Blu Greenberg at the

First JOFA International Conference

It was Rabbi Shlomo Riskin of Ohr Torah Stone who spearheaded the campaign to allow women to become to’anot, particularly in light of contentious cases in which recalcitrant husbands attempt to withhold the get (Jewish divorce) or try to use it as a bargaining chip in negotiations about finances or custody. He argued that divorcing women are more likely to reveal incidents of physical or sexual abuse as well as other intimate details to other women–and this kind of disclosure could significantly affect the decision of a beit din.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Chief Rabbinate of Israel agreed with Riskin’s proposal, and in 1990 Ohr Torah Stone created a training program in which female participants study Jewish law, marriage counseling, mediation, and negotiation for three years, and then take a rigorous exam administered by the rabbinate. This is the same exam given to men who wish to work as rabbinical advocates.

After the first class of Ohr Torah Stone participants passed the qualifying exam, the rabbinate became hesitant about allowing women to enter the previously all-male space of the rabbinical court. So the rabbinate changed the exam for the next year, making it so difficult that all candidates, male and female–with the exception of one woman–failed. However, a group of women, including to’anot and to’anot-in-training, appealed to Israel’s Civil High Court of Justice, which condemned the rabbinate’s exclusionary tactics.

Today, female rabbinical advocates commonly negotiate divorces in the Israeli beit din, thanks to organizations such as Yad L’isha, a legal aid center where graduates of the Ohr Torah Stone program offer advice and representation at no cost for women.

Yo’atzot Halakhah

In 1997, Nishmat, a Jerusalem-based Torah study center for women, began to train female halakhic advisors, or yo’atzot halakhah, qualified to answer questions regarding the laws of Jewish ritual purity (niddah). The details of these laws, which relate to menstruation as well as other issues of sexuality and women’s health, are subjects that some women are understandably uncomfortable discussing with a male rabbi.

A candidate to become a yo’etzet halakhah studies for two years at Nishmat and receives training from experts in psychology, women’s health, and sexuality. Since the first graduating class in 2000, 61 women have been certified as yo’atzot halakhah. These women work in Jewish communities in Israel and in North America and answer questions via phone and Internet from women around the world on topics in women’s health and halakhah, including issues of family purity, fertility problems, and sex education for teens.

The creators and graduates of this program are careful to call themselves halakhic experts or advisors–not halakhic deciders–to pre-empt objections that it remains the exclusive role of rabbis to give halakhic rulings (p’sak). Indeed, yo’atzot often turn to rabbis to resolve complicated issues. Due to the way the role is defined, the position of a yo’etzet is accepted in many Orthodox circles, including some that are to the right of center.

Women in Synagogue Leadership

Since the late 1990s, a handful of Modern Orthodox synagogues in the United States have created congregational leadership positions for women. While each synagogue has chosen a different title–community scholar, assistant congregational leader, education fellow, spiritual mentor–all these positions carry a job description that resembles much of what pulpit rabbis do, incorporating teaching and pastoral care.

Though the women who hold these positions might look like rabbis and sound like rabbis, they are careful not to call themselves rabbis. According to some liberal Orthodox thinkers, like Blu Greenberg, the opposition to women being called rabbi is sociological, psychological, and political–but not halakhic. Orthodox interpretations of Jewish law do prevent women from being witnesses or counting as part of a minyan, but women can do most of the jobs that male rabbis do, and Greenberg argues, if they have the required knowledge and training, they deserve the title.

Leaders in more right-wing Orthodox circles do not agree. Rabbi Hershel Schachter, a rosh yeshiva at Yeshiva University, argues that the laws of modesty should prevent women from functioning as rabbis. According to Schachter, Orthodox women are not discriminated against by this limitation but rather are privileged to maintain their modesty in an immodest world.

While a few women have received private ordination from Orthodox rabbis, most notably Haviva Ner David, Mimi Feigelson, these women have not been recognized as rabbis in mainstream Orthodoxy. In March 2009, after a defined course of advanced study, Sara Hurwitz received ordination from Rabbi Avi Weiss of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale as a Mahara”t, an acronym Weiss devised, which stands for “halakhic, spiritual, and Torah leader.” Committed to training more women to serve as religious leaders of synagogues, schools, and college campuses, Weiss opened Yeshivat Mahara”t in New York in fall 2009.

Time will tell if there will be jobs and positions for the graduates of Yeshivat Mahara”t, and if the Orthodox sensitivities to a woman being called rabbi will change as more qualified and learned women are seen in religious leadership roles. In the modern world, where women hold public positions in so many areas, it is certainly likely that an increase in the numbers of women with advanced religious education and leadership experience will make a serious difference to the Orthodox community.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

yeshiva

Pronounced: yuh-SHEE-vuh or yeh-shee-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, a traditional religious school, where students mainly study Jewish texts.