The unprecedented pogrom of November 9-10, 1938 in Germany has passed into history as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass). Violent attacks on Jews and Judaism throughout the Reich and in the recently annexed Sudetenland began on November 8 and continued until November 11 in Hannover and the free city of Danzig, which had not then been incorporated into the Reich. There followed associated operations: arrests, detention in concentration camps, and a wave of so-called Aryanization orders, which completely eliminated Jews from German economic life.

The November pogrom, carried out with the help of the most up-to-date communications technology, was the most modern pogrom in the history of anti-Jewish persecution and an overture to the step-by-step extirpation of the Jewish people in Europe.

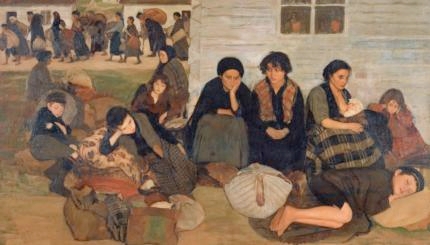

Jews Leaving Germany

After Hitler’s seizure of power, even as Germans were being divided into “Aryans” and “non-Aryans,” the number of Jews steadily decreased through emigration to neighboring countries or overseas. This movement was promoted by the Central Office for Jewish Emigration established by Reinhard Heydrich (director of the Reich Main Security Office) in 1938.

In 1925 there were 564,378 Jews in Germany; in May 1939 the number had fallen to 213,390. The flood of emigration after the November pogrom was one of the largest ever, and by the time emigration was halted in October 1941, only 164,000 Jews were left within the Third Reich, including Austria.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

READ: Sept. 16, 1935: Nazi Laws on Jews Put Into Effect

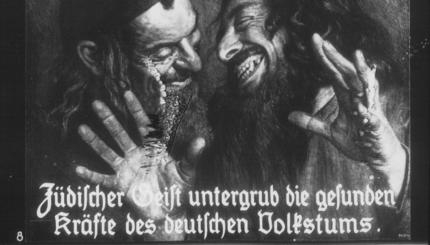

The illusion that the legal repression enacted in the civil service law of April 1, 1933, which excluded non-Aryans from public service, would be temporary was laid to rest in September 1935 by the Nuremberg Laws — the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor. The Reich Citizenship Law heralded the political compartmentalization of Jewish and Aryan Germans.

Economic Exclusion

The complementary ordinances to the Reich Citizenship Law, dated November 14-28, 1935, sought to define who was a Jew; it also created a basis for measures limiting the scope of Jewish occupations and the opportunities for young Jews to get an education. Following the March 1938 annexation (Anschluss) of Austria, which brought 200,000 Austrian Jews under German domination, exclusion of Jews from the economy began first through the removal of Jewish manufacturers and business chiefs and their replacement by “commissars” in charge of “aryanization,” the expropriation of Jewish businesses.

READ: Feb. 14, 1934: Jewish Agents Thrown Out of Reich System

Within a short time, from January to October 1938, the Nazis aryanized 340 middle-sized and small industrial enterprises, 370 wholesale firms, and 22 private banks owned by Jews. The November pogrom was the peak of a series of events intended to expel the Jews from economic life and to force a hurried emigration.

A sequence of normative legislation in 1938 heralded economic despoliation. Under the Law Concerning the Legal Position of the Jewish Religious Community (March 28, 1938), the state subsidy for the Jewish community was withdrawn. Under the decree of April 22, 1938 against “continuing concealment of Jewish business activity,” Jews were obliged to declare their assets–an indication that their possessions might be seized.

The Fourth Decree (July 25, 1938) under the Reich Citizenship Law deprived Jewish doctors, as of September 30, of their practices among Jewish patients. An edict by the police president of Breslau dated July 21 ordered that shops and businesses belonging to Jews should bear a notice: “Jewish Firm.” Air Ministry political-economic guidelines of October 14, 1938 were accompanied by a recommendation, summed up by Hermann Goring (then head of the ministry): “The Jewish question must now be grasped in every way possible, for they [Jews] must be removed from the economy.”

Goring also said that he was in favor of the creation of Jewish ghettos in German towns. His words gave notice of a general anti-Jewish offensive in the coming weeks. The most favorable opportunity for unleashing the attack was afforded by the fatal wounding of the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath on November 7th 1938 in Paris by the 16-year-old Polish Jew Herschel Grynszpan.

READ: Nov. 8, 1938: Polish-Jewish Youth, 17, Shoots Nazi Embassy Official in Paris

A Top-Down Pogrom

Ernst vom Rath’s death gave the signal to the Reich propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, to unleash the pogrom against the Jews. The news of the death was received by Adolf Hitler during the traditional dinner for the “old fighters” of the Nazi movement, held in the assembly room of the Old Town Hall in Munich on the anniversary of the bloody march on the Feldherrnhalle and the unsuccessful putsch of November 9, 1923.

The atmosphere for announcements of victory or incitements to hate and revenge was optimal, not only in Munich but also among Nazi organizations throughout the country, where Germans awaited the radio transmission of the customary memorial celebration and Hitler’s speech. The signal for retaliation had already been given by Goebbels (with Hitler’s agreement) in an unusually aggressive speech, which Hitler did not attend. The political propaganda initiative and management of the pogrom was in Goebbels’ hands, though he held no written authority from Hitler.

While the Fuhrer went to his Munich apartment, the propaganda minister told the Nazi notables and old fighters present that there had already been acts of revenge on November 8 in Kurhessen and Magdeburg against State Enemy No. 1 — the Jew. Synagogues and shops belonging to Jews had, he said, been destroyed.

His words were understood by his audience to signify “that while the party would not openly appear as the originator of the demonstrations, in reality it would organize them and carry them through” (secret report of supreme party judge Hans Buch to Hermann Goring, February 13, 1939). These intimations were immediately passed on by telephone to the headquarters of the various districts and were followed by telegrams from the Gestapo. Heydrich’s secret order, sent by teleprinter to all Gestapo offices and senior SD sections, was transmitted at 1:20 a.m. on November 10.

Once Goebbels had given the Nazi district leaders the impetus to unleash a massive pogrom, the further initiative lay in their hands. The execution of the pogrom, under direction of the highest Nazi party leaders, was entrusted to police and state agencies, to units of the SS, and in part to SA members. By means of the latest communications technology — telephone, teleprinters, police transmitters, and radio — within a few hours the pogrom had reached almost every part of the Reich without meeting any resistance.

Desecrated Synagogues, Looted Shops, Mass Arrests

During the night of November 9-10, 1938 Jewish shops, dwellings, schools, and above all synagogues and other religious establishments symbolic of Judaism were set alight. Tens of thousands of Jews were terrorized in their homes, sometimes beaten to death, and in a few cases raped. In Cologne, a town with a rich Jewish tradition dating from the first century CE, four synagogues were desecrated and torched, shops were destroyed and looted, and male Jews were arrested and thrown into concentration camps.

Brutal events were recorded in the hitherto peaceful townships of the Upper Palatinate, Lower Franconia, Swabia, and others. In Hannover, Herschel Grynszpan‘s hometown, the well-known Jewish neurologist Joseph Loewenstein escaped the pogrom when he heeded an anonymous warning the previous day; his home, however, with all its valuables, was seized by the Nazis.

In Berlin, where 140,000 Jews still resided, SA men devastated nine of the 12 synagogues and set fire to them. Children from the Jewish orphanages were thrown out on the street. About 1,200 men were sent to Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen concentration camp under “protective custody.” Many of the wrecked Jewish shops did not open again.

Following the Berlin pogrom the police president demanded the removal of all Jews from the northern parts of the city and declared this area “free of Jews.” His order on December 5, 1938 — known as the Ghetto Decree — meant that Jews could no longer live near government buildings.

READ: Dec. 5, 1938: Nazis Take Drivers’ Permits from Jews, Ban Use of Central Berlin

The vast November pogrom had considerable economic consequences. On November 11, 1938 Heydrich, the head of the security police, still could not estimate the material destruction. The supreme party court later established that 91 persons had been killed during the pogrom and that 36 had sustained serious injuries or committed suicide. Several instances of rape were punished by state courts as Rassenschande (social defilement) in accordance with the Nuremberg laws of 1935.

At least 267 synagogues were burned down or destroyed, and in many cases the ruins were blown up and cleared away. Approximately 7,500 Jewish businesses were plundered or laid waste. At least 177 apartment blocks or houses were destroyed by arson or otherwise.

It has rightly been said that with the November pogrom, radical violence had reached the point of murder and so had paved the road to Auschwitz.

Reprinted with permission from The Holocaust Encyclopedia (Yale University Press).