Like other literary classics, Job is a book which many believe they know but which few have actually read. It is long, difficult, at times tedious. It is also, quite simply, one of the most subtle and penetrating examinations of the persistent problem of theodicy: in a world so rife with evil, where goodness seems fragile at best, can one affirm that the arc of history still bends toward justice? Or in traditional theological terms, why does a good and powerful God permit so much evil in our world? While a book that so flamboyantly questions the moral order of the universe, and even God, does not obviously fit into the Hebrew Bible, it is at home in the Western Canon, a source of inspiration for writers ranging from Shakespeare to Kafka.

University scholars are at a loss as to when and why the Book of Job was written. This is in part because of its unusual structure. It opens with a prose story about a good and righteous man named Job who, through no fault of his own and simply because of God’s bet with Satan, the angelic prosecuting attorney, is unjustly tormented. Satan bets that Job is only fastidious in his worship because God has graced him with abundance. Take that away, says Satan, and Job will turn quickly and curse God. God has more faith in Job but allows Satan to afflict him in order to see how His righteous servant will respond to a sudden change of fortune. Job loses his wealth, his health, and all his children — is left sitting in a heap of rags, picking at his leprous skin. But he does not curse God.

The prose narrative is then interrupted by a long cycle of poems in which Job alternately speaks with his friends about his anguish, and at and through them to the hidden God whom he holds responsible for the intolerable injustice of his situation. Then God appears to Job in a whirlwind and delivers a stinging rebuke, and finally the narrative voice returns to report that God has restored Job’s wealth and health, and given him new children, three of whom, the daughters, are singled out for their beauty.

Most scholars believe that the framing narrative of the book, its prologue and epilogue, derive from an ancient folk tale and that later hands produced the intervening thirty-nine chapters of poetry. The Rabbis of the Talmud, who shaped and sealed the Biblical canon, could not agree whether the Book of Job was to be read as an historic account or a moral parable, or whether its protagonist was Jew or gentile, but somehow they knew that the Book of Job had to be included in the Hebrew Bible.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The prologue of the book presents God as a foolish and dangerous monarch, not unlike Ahasuerus, the capricious Persian king in the Book of Esther. As if he were a rich husband jealously brooding over whether his young, beautiful wife really loves him or only married him for his wealth, God abuses his loyal servant, Job, in order to test the depth of his love. Initially, Job cloaks his pain and fury in words of ritual piety directed at God, but when his wife, who with him has suffered the sudden deaths of their ten children, advises him to “curse God and die,” he gives vent to his rage: “You speak like a wicked fool, woman! Shall we accept good from God and not evil?!” And she, grieving and broken-hearted, disappears altogether from the text, banished even from the final scene of restoration described in the epilogue.

Interestingly, two American poets, Archibald MacLeish and Robert Frost, in their Job-inspired works, the play, J.B. and the comedic poem, “Masque of Reason,” bring Mrs. Job back for a happy ending, a choice that turns the Book of Job into a comedy. The Hebrew Bible, however, not averse to tragedy, allows things to break and remain broken. Moses, who led the Israelites out of slavery, never gets into the promised land. And although Job gets new children with whom he establishes an intimacy he had not known before, his wife has no part in that new chapter, her absence bearing witness to the incompleteness of the restitution.

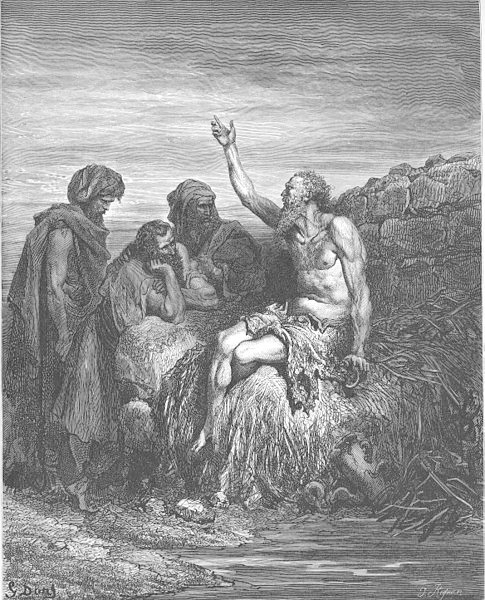

While framed by a tale of affliction and recovery, the body of the Book of Job, its rich ambiguous poetic center, is structured as a dramatic conversation among friends, Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar, who’ve come from a distance to comfort and console Job.

For a week they sit with him in silence until, on the eighth day, Job begins to speak:

God damn the day I was born

and the night that pushed me from the womb. On that day—let there be darkness;

let it never have been created;

let it sink back into the void…If only I had strangled or drowned

on my way to the bitter light.

Now I would be at rest,

I would be sound asleep…Why is there light for the wretched,

life for the bitter-hearted,

who long for death, who seek it

as if it were buried treasure…My worst fears have happened;

my nightmares have come to life. Silence and peace have abandoned me,

and anguish camps in my heart.”

The companions had long admired, and perhaps envied, their dignified and pious prince of a friend, but now, already devastated by the sight of him reduced to sitting naked on an ash heap, scraping his inflamed skin, they are unable to abide his words. Outraged and frightened by his unwillingness to take shelter in the arms of a just and benign Providence, the friends abandon commiseration and go to battle for God:

“Have you lost all faith in your piety,

all hope in your perfect conduct?

Can an innocent man be punished?

Can a good man die in distress?”

“You are lucky that God has scolded you;

so take his lesson to heart.

For he wounds, but then binds up;

he injures but then he heals…”

But Job will have none of it:

“God has ringed me with terrors,

and his arrows have pierced my heart…You too have turned against me;

my wretchedness fills you with fear…”

The argument between the friends does not conclude; it simply fizzles to a stop in mid-speech, Job getting the last word:

“Oh if only God would hear me,

state his case against me,

let me read his indictment.

I would carry it on my shoulder

or wear it on my head like a crown.

I would justify the least of my actions;

I would stand before him like a prince.”

And then God turns up! His voice emerges from a whirlwind and speaks a long, majestic oration which seems to batter Job into meek submission before the unknowable Mystery. But although Job claps his hand to his mouth, he does get out a few ambiguous words in response to the storm:

“I had heard of you with my ears;

but now my eyes have seen you.

Therefore I will be quiet,

comforted that I am dust.”

One of the Talmudic rabbis condemned Job for having related to God as if he were arguing with a friend. “Can one be friends with Heaven?” he wonders. Another rabbi, struck by Job’s strong yearning to die, observed, “Either friends like Job’s, or death.” Shall we say that Job’s friends kept him in life because they, like God, turned up when the chips were down?

Want to get to know more amazing, complicated, and relatable biblical personalities? Sign up for a special email series here.