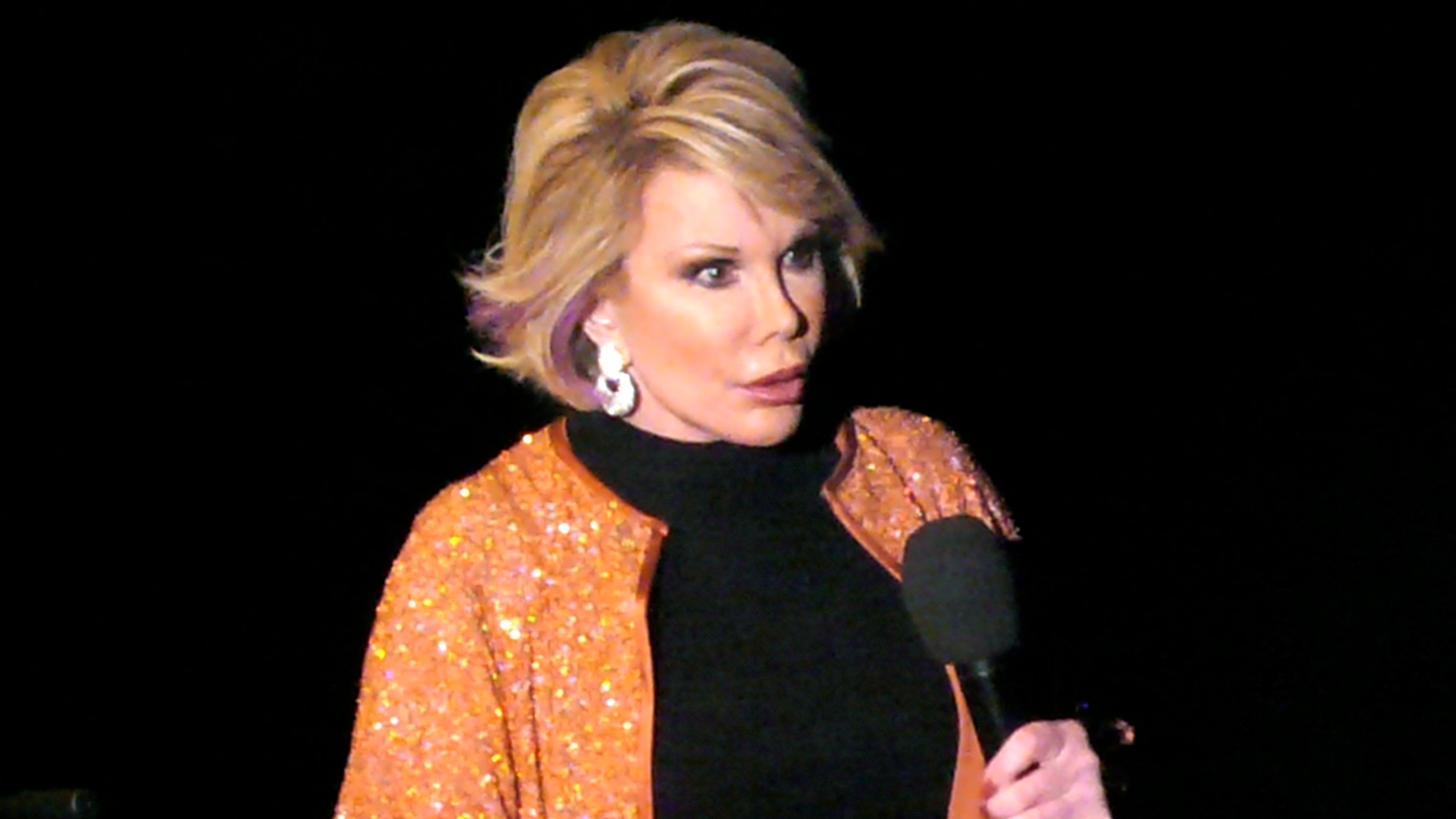

Note: This article was written before Joan Rivers’ death in 2014 at age 81.

“Can we talk?” In the minds of millions of Americans, this common phrase conjures up the image of Joan Rivers, the woman who realized in the mid-1960s that “the country was ready for something new–a woman comedian talking about life from a woman’s point of view” (Enter Talking).

In revues, nightclub acts, and concert halls (in the early 1960s), and to a vast new audience via television in the 1970s and 1980s, Joan Rivers popularized and perfected a genre of comedy that challenged reigning social conventions. Her willingness to “say what is really on everyone’s mind” was coupled with an ingénue quality. This made her a less-than-threatening figure and enabled her to popularize the type of monologue that had previously been the domain of male comedians: Their acts combined social criticism with sharp wit, and Rivers was soon to join them.

She paid homage to these pioneers in her 1986 autobiography, Enter Talking. Hearing Lenny Bruce perform in the village was for her “an event that forever changed my comedy life…. Boom! there he was, an obscenity among the pleasant routines of the Establishment” (Enter Talking).

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Influenced by Bruce, Rivers worked assiduously on her own routines and became a skillful crafter of comedic scripts for herself and others. Among her early writing credits are routines for the Phyllis Diller Show, episodes of Candid Camera, and material for Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show.

It was on the Tonight Show, in 1965, that Rivers got her big national break. Introduced as one of the writers for the show, she and Carson engaged in a hilariously funny dialogue. As Rivers remembered it, “At the end of the show he was wiping his eyes. He said, right on the air, ‘God you’re funny. You’re going to be a star'” (Enter Talking).

Parental Background

Born in Brooklyn, New York, as Joan Alexandra Molinsky on June 8, 1933, Rivers was the youngest daughter of Beatrice (Grushman) and Meyer Molinsky, a doctor. Both of her parents were Russian Jewish immigrants from the Odessa area. Despite the geographical proximity of their origins, Rivers’s parents came from vastly different socioeconomic circumstances.

Meyer Molinsky’s family had been poverty-stricken in Russia, and they remained poor in their early years in America. Molinsky’s entry into the medical profession propelled the family into the emergent Jewish middle class of Brooklyn.

Beatrice Molinsky’s family had been very wealthy merchants in Odessa but left everything behind in the Old Country. That loss of status forever haunted Beatrice Molinsky, and she continually pushed her husband—a struggling general practitioner in the heavily Jewish Brownsville section of Brooklyn—to earn more money.

The conflict between her parents (“My mother wanted M.D. to stand for Make Dollars”) was the inspiration for many of Rivers’s early routines. The constant arguments in the family about money left her with a permanent sense of insecurity that she mined for its comedic value. The epilogue to Enter Talking concludes in this way: “She lives the life her mother longed to have—but still believes that next week everything will disappear.”

Education

From earliest childhood, Rivers wanted to be an actor. Her mother wanted her youngest daughter to prepare herself for marriage and entry into polite society. The tension between these aspirations deeply influenced the young woman’s life and craft.

Educated in Brooklyn’s Ethical Culture School and Adelphi Academy, Rivers was an enthusiastic participant in the school drama and writing programs. At Adelphi, she founded the school newspaper. At Connecticut College and later at Barnard, she read widely in the classics and took courses in the history of the theater. Though she was later to project a scatterbrain image, the key to her craft lies in her classical education and her ability to turn out witty monologues and dialogues.

In 1954, Rivers graduated from Barnard College with a degree in English literature and was awarded membership in Phi Beta Kappa. After college, she took an entry-level job at a firm in the New York fashion industry. She soon gave it up for a short-lived (and disastrous) marriage to the boss’s son. “Our marriage license turned out to be a learner’s permit” (Enter Talking).

Early Ventures in Entertainment

Determined to succeed in the theater, Rivers did temporary office work while auditioning for roles in Off- and Off-Off-Broadway plays. In 1960, she developed comedy routines that gained some attention and in 1961 got her first big break when she joined the Second City Comedy troupe of Chicago. Her improvisational and writing skills shone at Second City.

Within a few years, she was a regular at New York City comedy clubs, foremost among them the Duplex and the Bitter End. In her act, she joked about sex in a way that was both shocking and endearing. Female comedians had not spoken with such frankness before. “I knew nothing about sex. All my mother told me was that the man gets on top and the woman gets on the bottom. I bought bunk beds” (Still Talking).

It was from these clubs that Rivers was catapulted to fame by her appearances on national television. Throughout the first decade of her career she continued to write, perform in clubs, and appear on television.

The 1970s saw Rivers venture into other entertainment media. While her Broadway play Fun City was greeted with a mixed reaction, her comic 1973 TV movie, The Girl Most Likely To, was the most successful made-for-TV movie of its time. Its theme—the revenge of a woman jilted for her looks—was the harbinger of a new direction in writing about women’s issues. Two of her books, Having a Baby Can Be a Scream (1975) and The Life and Hard Times of Heidi Abramowitz, were also great successes—as were her 1986 autobiography, Enter Talking, and its sequel, Still Talking (1991).

Starting a Family

During her rise from stand-up comic to television personality, Rivers married producer Edgar Rosenberg. He became her de facto manager, and together they embarked on a number of entertainment ventures, including the ill-fated The Late Show Starring Joan Rivers. Their marriage, described in some detail in Still Talking, was inextricably linked to both of their careers. They had one child, Melissa Rosenberg, born January 20, 1968.

In 1987, Edgar Rosenberg committed suicide. Rivers’s reaction was feisty and characteristic: “The best therapy for me would have been to go right from the mortuary to the stage, but my advisers agreed it would have been unseemly.”

Seven years later, in 1994, Rivers dealt with this tragedy and its aftermath in her NBC movie Tears and Laughter. In this film, Rivers and her daughter Melissa play themselves and demonstrate, as Gina Bellafante noted in Time magazine, “the sunny conviction that the saga of their cruel lives will serve as a morality tale…. It also manages to convey a message about the capacity for survival.”

In that same year, Rivers wrote and produced a Broadway play, Sally Marr and Her Escorts. Based on the life of Lenny Bruce’s mother, it too deals with the cruel price that celebrity and talent exact from those blessed and cursed with its gifts.

Since 1995, Joan Rivers had been a host for the E! Entertainment television network, where she and her daughter broadcast their “Joan and Melissa’s E! Fashion Reviews” from the scene of the annual Golden Globe, Emmy and Academy Award ceremonies. Rivers herself won the 1990 Emmy award for best daytime talk show host.

Jewish Identity

Joan Rivers was supportive of Jewish philanthropic and social causes and was a former Hadassah Woman of the Year. In her books, she made reference to Jewish holidays and rituals, as well as very trenchant and witty remarks about American Jewish social phenomena—including the Catskill Mountains Borscht Belt, where she performed early in her career.

In Enter Talking, there is a particularly moving account of her first Yom Kippur away from the warmth–and fury–of her family. Her portrayal of her own family’s Jewish life provides us with confirmation of Jenna Weissman Joselit’s observation in The Wonders of America (1994) that, for American Jews, “the Jewish home was now placed at the core of Jewish identity, often becoming indistinguishable from Jewishness itself.”

Reprinted from Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.