If we define midrash as “homiletic or legal interpretations of the Bible,” that is, interpretive readings of sacred text, then the process of midrash certainly continues today–in two formats. There are contemporary commentaries written on the Bible, often reflecting the needs and interests of the day. And secular culture commonly adapts religious themes for artistic purposes.

Contemporary Commentary

As an example of the first, the “rabbi’s sermon” given in the modern synagogue is often a midrash-like exposition on the week’s Torah reading; by attempting to relate Torah to life today, the sermon is the example par excellence of contemporary Midrash. It is not uncommon for a contemporary rabbi to hold an ancient midrashic text in one hand, and a news clipping from the daily paper in the other, as he or she tries to make sense out of the present by searching for meaning in the past.

Works like Ellen Frankel’s The Five Books of Miriam are another prime example. This is a collection of modern midrashic statements put into the mouths of women to answer the question “What did women then, and what do women now, make of the events in this chapter?” Here is one such selection from The Five Books of Miriam:

“Our daughters ask: Why does Jethro advise Moses to appoint only men to help him share the onerous burden of leadership? As it is written: “Seek out capable men who fear god, trustworthy men who spurn ill-gotten gain” (Exodus 18:21). We can’t believe that there weren’t capable, God-fearing women among the people.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

“The sages in our own time answer: We must be careful not to judge Jethro by the standards of 20th-century Western democracy. After all, in his time and place, women generally did not occupy such leadership roles.

“Lilith the rebel counters: But we can hold today’s Jethros in our own communities to such standards! Especially since the burdens of leadership have not gotten any lighter–and since capable, God-fearing, trustworthy women now stand ready to share them.”…

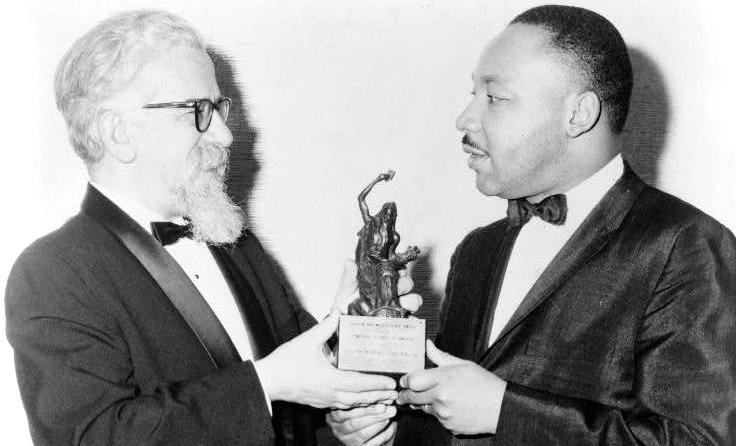

The Midrash of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Midrash can be “done” by Christians, as well as by Jews, though the process would have a different name and would draw on a different set of techniques and values, since “midrash” is a uniquely Jewish product. In Deuteronomy, chapters 31-34, Moses gives his final farewell to the Israelite nation. God instructs Moses to go to the top of a mountain, to see the land that the Israelites will soon enter but that he will not. Moses’ final speeches are poignant and moving: The greatest leader will see his goal accomplished by others, yet he himself will not arrive there.

Compare these chapters in Deuteronomy to the famous “I See the Promised Land” speech by the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., given on April 3, 1968:

“Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

By ending with a stirring message about seeing the promised land from the mountaintop, Dr. King evoked images of Moses entering the land. This midrash turned out to be prophetic, for King was assassinated the very next day.

One of the oldest collections of midrash, if not the oldest, is the Passover Haggadah. The process of midrash on the Exodus story remains alive and well in modern haggadot. There are literally hundreds of Haggadah interpretations, each giving its own spin on the verses from Exodus–an archaeological Haggadah, a feminist version, an Israeli version that focuses on the fulfillment of God’s promise to redeem us.

Movie Midrash

Yet, the process of interpreting the Bible and of writing Midrash, especially on the Exodus theme, goes well beyond these works. In the biblical account, we are told that Moses was placed in a basket on the Nile by his mother, that Moses’ sister watched as the daughter of Pharaoh came to bathe in the Nile and saw the basket. [She took Moses and raised him as her own.]…

The Bible does not tell us how Moses finds out he is a Hebrew, only that “he went out to his kinsfolk.” The few details in the biblical story led to many midrashic interpretations, including those in the 1998 movie The Prince of Egypt. This is from the story line of The Prince of Egypt:

“That night as Moses returns to his room, he discovers that Tzipporah has escaped. Intrigued by the rebellious girl, he follows her through the Hebrew settlement of Goshen, where he comes upon his true siblings, Miriam and Aaron. Believing that Moses has returned to help them, Miriam reveals to Moses the truth about his identity, that he is the son of a Hebrew slave. Shocked and dismayed, Moses refuses to believe her and flees back to the palace. That night he has a nightmare about the slaughter of the newborn Hebrews many years ago.”

The movie’s authors and producers added many details to the terse biblical narrative. They have Tzipporah, Moses’ future wife, meeting him in Egypt, where in the biblical account he meets her later, in Midian. The Bible does not tell us exactly how Moses found out he is a Hebrew, while in the movie, “Miriam reveals to Moses the truth about his identity, that he is the son of a Hebrew slave.” These are plausible answers to questions about the Exodus story. Yet, they–as well as much of the Prince of Egypt animated feature–are a midrash, filling in the holes for those curious about what exactly took place….

Art, Music, & Literature

The process of Midrash can also be seen in art, music, and literature. Chagall’s paintings are often modern expressions of traditional themes. The spiritual hymn “Let My People Go” took a well-known phrase from the Bible, one that Moses directed to Pharaoh, and reframed it as referring to blacks talking to Southern slave owners.

Let’s look at a modern midrash on Ecclesiastes, Chapter 3. Here is a [partial] translation of verses 1 to 8:

“To everything there is a season,

And a time for every purpose under heaven:

“A time for being born and a time for dying,

A time for planting and a time for uprooting the planted;

A time for slaying and a time for healing…

“A time for loving and a time for hating;

A time for war and a time for peace.”

The 1960s hit “Turn, Turn, Turn,” sung by the Byrds and written by folk singer Pete Seeger, begins as a fairly straightforward musical presentation of the Bible text.

Chorus:

“To everything, turn, turn, turn,

There is season, turn, turn, turn,

And a time for every purpose under heaven.

“A time to be born, a time to die,

A time to plant, a time to reap,

A time to kill, a time to heal,

A time to laugh, a time to weep.”

And the second stanza is also faithful to the biblical text:

“A time of love, a time of hate,

A time of war, a time of peace,

A time you may embrace,

A time to refrain from embracing.”

Seeger leaves out certain verses and rearranges the sequence, but the song retains the flow of the biblical text–untilthe last lines. Where Ecclesiastes ends with “A time for war, and a time for peace,” the Byrds’ hit adds a 1960s anti-war postscript to reflect the mood of the time:

“A time to love, a time to hate,

A time of peace, I swear it’s not too late.”

The author of Ecclesiastes states that there is a time for everything in life, predetermined by a power beyond our control. Pete Seeger’s song completely changes the meaning: War and peace are in the hands of human beings; the choices that people make can change the world.

The list goes on and on: Leonard Bernstein’s Jeremiah is an example of music-as-midrash. John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, and (more recently) Anita Diamant’s The Red Tent each took a biblical theme and wove it into a story, creating a literary midrash of its own.

Making Midrash

The Rabbis took the Bible seriously, searching for new and deeper meaning from the text and for an understanding (or, better, understandings) that spoke to their day and age. Our attempts to understand and interpret the Bible today–be they literary (like classic midrashim), musical, or artistic–demonstrate that we, too, are trying to incorporate sacred scripture into our own lives.

By confronting sacred text and engaging in a struggle with it, we affirm its sanctity and relevance in our lives. We engage in midrash with a sense of awe, with an appreciation that we stand in the presence of something sacred, something holy, something of ultimate importance.

Excerpted with permission from Searching for Meaning in Midrash (Jewish Publication Society).

Haggadah

Pronounced: huh-GAH-duh or hah-gah-DAH, Origin: Hebrew, literally "telling" or "recounting." A Haggadah is a book that is used to tell the story of the Exodus at the Passover seder. There are many versions available ranging from very traditional to nontraditional, and you can also make your own.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.