We associate the settling of the American frontier with pioneers in covered wagons and cowboys fighting Indians. We less frequently identify it with the peddlers and merchants who sustained the early settlers, shared their hardships and improved the quality of their lives. Starting in the 1840s, Jews from German-speaking lands seeking opportunity in America chose the difficult life of a peddler. They trudged America from rural New England to Gold Rush California.

In his “Reminiscences,” Isaac Mayer Wise, the founder of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, unsympathetically recalled that, by 1846, there were different classes of German-Jewish peddlers already established in America:

(1) The basket peddler—he is altogether dumb and homeless;

(2) the trunk-carrier who stammers some little English, and hopes for better times;

(3) the pack-carrier, who carries from one hundred to one hundred and fifty pounds upon his back, and indulges the thought that he will become a businessman some day.

In addition to these, there is the aristocracy, which may be divided into three classes:

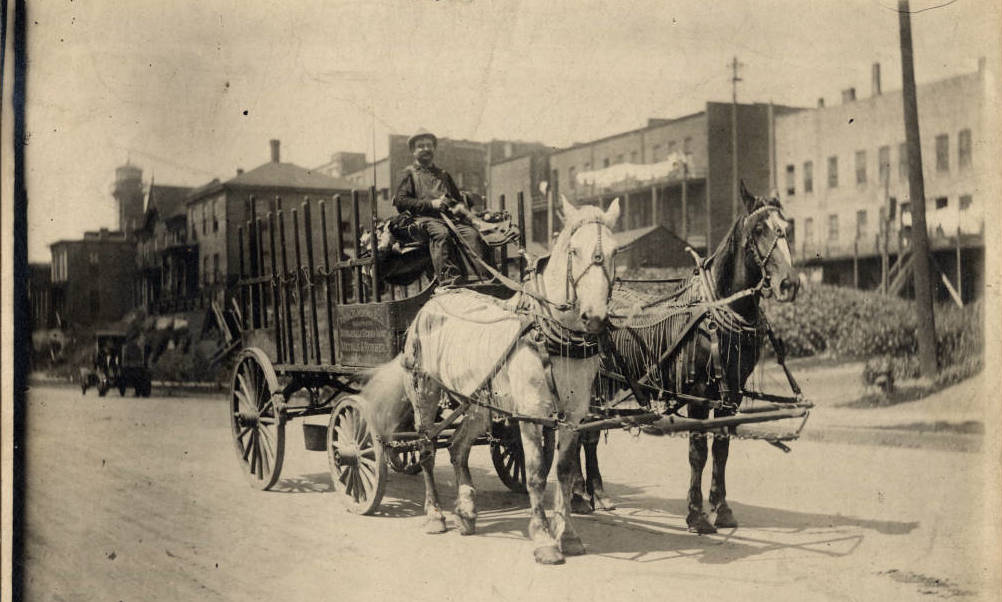

(1) the wagon-baron, who peddles through the country with a one or two horse team;

(2) the jewelry-count, who carries a stock of watches and jewelry in a small trunk, and is considered a rich man even now;

(3) the store-prince, who has a shop and sells goods in it.

Wise observed of these peddlers, “At first one is the slave to the basket or the pack; then the lackey of the horse, in order to become, finally, the servant of the shop.” Despite its constraints, for most peddlers owning a store seemed far better than trudging the roads.

Abraham Kohn’s experiences in rural New England were typical of the travails facing back packing Jewish peddlers. Beyond the risk of theft, loss, accident or illness, peddlers fought against the weather. In winter 1842, trudging near Lunenburg, Massachusetts, the recently arrived Kohn noted in his diary, “We were forced to stop on Wednesday because of the heavy snow.” He continues:

We sought to spend the night with a cooper, a Mr. Spaulding, but his wife did not wish to take us in. She was afraid of strangers, she might not sleep well; we should go on our way. And outside their raged the worst blizzard I have ever seen. Oh, G-d, I thought, is this the land of liberty and hospitality and tolerance? Why have I been led here?

The incident ended happily. “After repeatedly pointing out that to turn us forth in a blizzard would be sinful, we were allowed to stay. She became friendlier, indeed, after a few hours, and at night she even joined us in singing.”

The peddler’s life posed challenges for Jews wishing to maintain their religion. In March of 1843, Kohn reports:

I came to Worthington, where I met a peddler named Marx … married and an immigrant . . . Wretched business! This unfortunate man has been driving himself in this miserable trade for three years to furnish a bare living for himself and his family. O G-d, our Father, consider Thy little band of the house of Israel. Behold how they are compelled to profane Thy holy Torah in pursuit of their daily bread. In three years this poor fellow could observe the Sabbath less than ten times … This is religious liberty in America.

Eventually, Abraham Kohn settled in Chicago, became a retail storeowner and a leader of the city’s Jewish community.

Not all German Jewish peddlers recalled their years on the road unfavorably. Isaac Bernheim, who arrived in the United States just after the Civil War and had a successful business career in Louisville, Kentucky, fondly described his years carrying a pack:

The new avocation afforded me many opportunities to familiarize myself with the language and customs of the people and with the country itself as perhaps no other pursuit could. It developed me physically, and what was worth still more to me, it gave me a spirit of independence and self-reliance which stood me in good stead afterward . . . I trudged along the peaceful Pennsylvania highways dreaming of future triumphs.

Jewish merchants brightened the lives of their clientele. Meyer Guggenheim, who later made a great fortune in copper and silver mining, proudly recalled that he started his career with a pack on his back, going from farm to farm trying to convince the mistress of the house to purchase shoe laces, needles, spices or ribbons. His biographer observed:

If the housewife was in a receptive mood and had a little spare cash, Meyer was greeted not without respect. As he slung his pack to the floor, the children crowded about to peer into its awesome, delightful depths and reinforce his halting English with cries of joy . . . In time housewives began to expect the monthly visit from the cheerful, friendly young Jewish peddler.

Several significant American Jewish families — the Gratzes of Kentucky, the Strauses of Georgia and New York, the Bambergers and Blooms of Louisville, the Fels’s of Philadelphia — got their start as peddlers. When new methods of manufacturing, transporting, and marketing goods rendered peddling obsolete, they opened retail shops and, eventually, department stores. These former peddlers revolutionized the way Americans purchased consumer goods. From such modest beginnings the great American consumer culture has been built.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.