Commentary on Parashat Shmini, Leviticus 9:1-11:47

George Bernard Shaw, the Irish playwright and writer, once said “the single biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

Communication is the foundation of community – both words come to English from the Latin word communis, meaning “shared by all or many.” This same idea is transmitted by our Sages of Blessed Memory in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of Our Fathers) where we learn: “…two who sit and have words of Torah between them, the Divine Presence is between them…” (Avot 3:2). Torah is not viewed as being limited to the actual five books of the scroll of a Torah, but is rather a euphemism for the Jewish way of life and for Jewish values as a whole. We find this confirmed in other rabbinic opinions, notably in the statement derived from Midrash: “decency (derekh eretz) precedes Torah,” (i.e., Tanna D’bei Eliyahu Ch. 1). At the core of community is communication, and at the core of communication is decency.

So much of the breakdown in our political processes, the breakdown in our public discourse, the near-total partitioning of American (and even global) society has been chalked up to the “echo chamber” phenomenon encouraged by the ways in which we share information in this era of social media. We are literally having separate conversations! We give precedence to viewpoints to which we already adhere, and we find ways to dismiss those ideas that seem to contradict that which we already believe. And yet, the Jewish tradition encourages us to always communicate openly, to share ideas even when they contradict and, most importantly, to seek to learn from those perspectives which do not conform to our own. This is emphasized in the Talmudic tradition:

Why did the House of Hillel merit to have the law affixed according to their perspective? Because they were pleasant and patient, and they taught both their own perspective and that of the House of Shammai. Not only that, but they actually gave precedence to the perspective of the House of Shammai before their own perspective. (Eiruvin 13b)

We have a similar lesson in this week’s Torah portion, Parashat Shmini.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

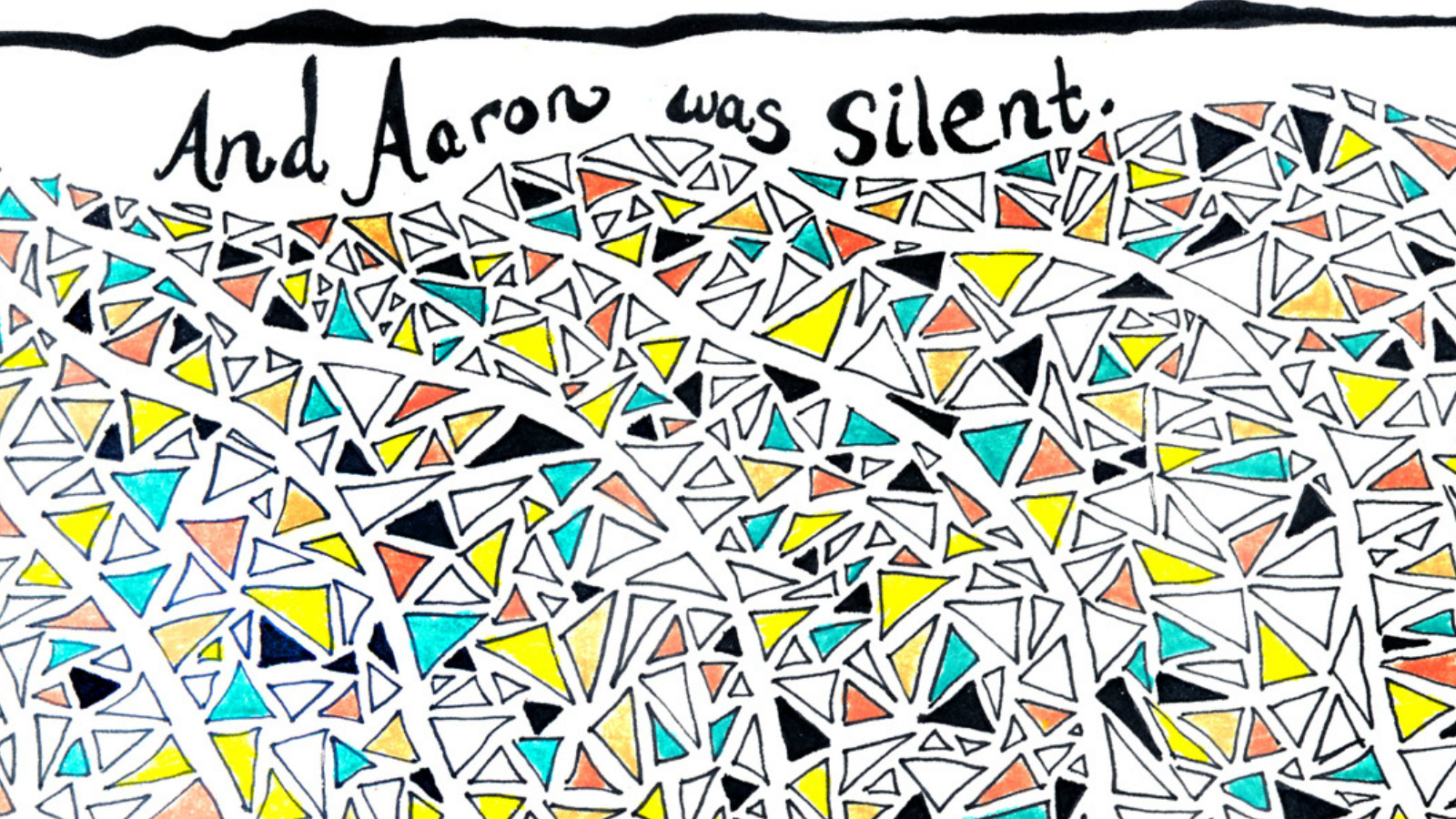

Towards the beginning of our Torah portion we read about Nadav and Avihu, the sons of Aharon the Priest, who bring a “strange fire” which — depending on how one translates and interprets — they were either not commanded to bring, or perhaps they were commanded not to bring. Ultimately they are consumed by fire inside the Mishkan, or Tabernacle. The Torah tells us, “The sons of Aharon, Nadav and Avihu, each man took his censer,” (Lev. 10:1). Focusing on this last phrase the Midrashic tradition provides us with this insight: “…this teaches us that each man acted alone and they did not communicate one another…to teach us that they entered without communication.” (Sifra Shmini 2:32, Vayikra Rabbah 20:8).

When seeking to establish a community grounded in values and decency, it becomes easy to view those who share a different perspective as an enemy or an adversary. Yet, the Jewish tradition comes and pushes us to see beyond this black-and-white dichotomy — to step into the gray and learn what discernible truths there may be even, or perhaps especially, in those viewpoints that contradict our own.

In a time in which we can see the breakdown of communication before our very eyes, it becomes all the more important to commit ourselves to open dialogue and communication grounded in decency and respect. Likewise we must remind ourselves that our communities are “shared by all or many,” and it is precisely in the gray area of these diverse viewpoints in which we will find, in the words of Pirkei Avot, the Divine Presence.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

parsha

Pronounced: PAR-sha or par-SHAH, Origin: Hebrew, portion, usually referring to the weekly Torah portion.