In classic Jewish style, the fundamental model of Tisha B’Av is a reenactment of that tragic historical orienting event. In going through the four historical fast days, Jews relive the stages of destruction of the First and Second Temples as well as the loss of Jewish sovereignty. (It is interesting, in light of the role that food plays in Jewish culture, that intense grief and guilt are expressed by giving up food!)

While the primary model is reenactment, the halacha [Jewish law] also draws upon its imagery of grief for a dead member of the immediate family. There is this difference, however, between grief over death of a loved one and mourning an historical tragedy: In the case of a death in the family, the shock of loss sets in motion the sorrow and mourning that come pouring out in the shiva, the seven days of mourning that come after the death and burial. When reliving historical tragedy, one knows the outcome at the outset. Thus, the sense of doom and grief builds up before the day actually arrives. The day of Destruction is a culmination of the grief, but immediately thereafter–since nothing can be done to prevent the tragedy from happening–the psychological balance shifts toward the renewal of life.

The first fast day in the sequence is the 10th day of Tevet, the day on which the siege of Jerusalem began in 586 B.C.E. However, since the day occurs more than six months before the date of the actual destruction, the pang of recollection on this day has not had so much resonance. The same can be said of the last day in the sequence, the Fast of Gedaliah, occurring the third of Tishrei. Coming two months after Tisha B’Av and dwarfed by the propinquity of Yom Kippur, the Fast of Gedaliah has had a limited impact. Both of these fast days begin at dawn, whereas Tisha B’Av starts at sundown on the previous night. On Tisha B’Av, the sorrow is so total that it goes beyond fasting to giving up such other pleasures as washing, cosmetic anointing of the body, and sexual relations. Not so the other three fast days, on which deprivation is limited to fasting.

The primary liturgy of grief for the destruction is acted out in the three-week period between the 17th day of Tammuz and the ninth of Av. It should be noted that these two days antedate the Talmud. When the Rabbis brought the two days together in a choreography of grief reenactment, the three weeks were gradually filled in, to help the mourners recreate the rising crescendo of destruction. The halacha structured the entire period into five stages of grief, corresponding to the imminence of catastrophe. The underlying experience that the individual should live through is that of a first-century Jerusalem defender who goes through the siege from inception to becoming a prisoner of the Romans at the climax.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Stage One: 17th of Tammuz

17 Tammuz: The wall of Jerusalem has been penetrated by the Romans, a clear signal that the end is coming. Jews, feeling the shock of forthcoming destruction, do not eat from sunrise to sunset. Penitential prayers are recited, summoning up the many terrible occurrences on this day.

Stage Two: Reenacting the Siege of Jerusalem

After this day, the intensity drops as people settle in for the terminal state of siege. The final part of the siege is reenacted during we three weeks between the two terminal days (17 Tammuz to 9 Av). While the city of Jerusalem is gradually reduced, Jews correspondingly intensify their grief and anxiety. Weddings are prohibited because the joy of marriage is incompatible with the mood of sorrow. Engagements are permitted for fear that by postponement they may be lost, though engagement parties are not held.

There are other grief rituals during the three weeks: taking no hair-cuts (in ancient times, letting hair grow long was a sign of mourning) and performing no acts that would inspire a blessing of Shehechiyanu (the blessing for something new and joyful), such as buying new clothes, a new home, a new car, or eating a new fruit for the first time in a year. (If the fruit will no longer be available after Tisha B’Av, this restriction is waived on Shabbat because on the Sabbath the fantasy of a perfect world still operates).

The symbolic statement in these self-denials is: Who has the faith to go out and buy new things or plan for the future? Who has the heart to try to look good when the end is clearly drawing near?

Throughout the three weeks, prophetic portions that proclaim Israel’s sin and the forthcoming destruction are read in the synagogue. The last of these prophetic phillipics, Hazon Yeshayahu, the Vision of Isaiah (Isaiah 1), is a devastating critique of the sin and corruption of Israel. In anticipation of sorrow, the portion is sung in the melody of Eicha, the Lamentations of Tisha B’Av. Hazon is always read on the Shabbat preceding the ninth of Av; that Shabbat has become known as Shabbat Hazon (vision).

Stage Three: Countdown of 9 Days

From the beginning of the month of Av, there is a countdown of nine days to destruction. The grief intensifies. In the initial Talmudic phase, the most intense mourning rituals were observed during the week in which Tisha B’Av itself occurred. Over the years, however, the entire nine days have become a unit of mourning among Ashkenazi Jews. Sephardic Jews generally restrict these deprivations to the immediate week in which Tisha B’Av occurs.

A folk saying goes, “When Av begins, cut back joy.” Home construction or painting is held off (with exile imminent, who would build or improve his home?). Orthodox practice prohibits the eating of meat and the drinking of wine. (Symbolically, “The anxiety is crippling my capacity for enjoying life”; “I’m losing my appetite.”)

Interestingly, these deprivations are also rituals of an onen (that is, one who has lost an immediate family member but has not yet buried him.). It is as if people know the Temple is doomed but have not yet reached the full acceptance symbolized by burial.

Fresh clothes are a source of pleasure, so laundering and dry cleaning are postponed (diapers are exempted). Total bathing is given up except for Shabbat, hence there is no swimming in that period, according to the Orthodox tradition. Symbolically, the noise of the Roman armies approaching disrupts the ease and order of daily life.

Stage Four: The Last Meal

The last meal on the day before Tisha B’Av — the Seudah Mafseket, the meal that separates eating from fasting — is highly restricted. It is as if Jews already feel the grief of the survivor or the severe loss of appetite felt by a war prisoner. Since people want to be able to fast well, lunch is generally a full meal, but in the late afternoon, a simple meal is eaten without multiple courses. In many families people even eat separately to avoid the festive aspect of a mezuman (a trio for grace). Some people eat eggs and/or beans (the food of mourners because their circularity evokes the idea of the wheel of fate and of silent mourning). Some eat only bread and water, even dipping a piece of bread in ashes before eating.

In Jewish ritual, mourners give up wearing leather shoes because they are comfortable. Besides, those who have just experienced the powerful loss of death do not want to wear something manufactured from animal skin, that is, something derived from death of another. Therefore, shoes are exchanged for canvas sneakers or sandals before sundown (unless the day preceding Tisha B’Av is Shabbat, in which case public display of mourning is inappropriate; in such a case, sneakers are not put on until after Shabbat ends).

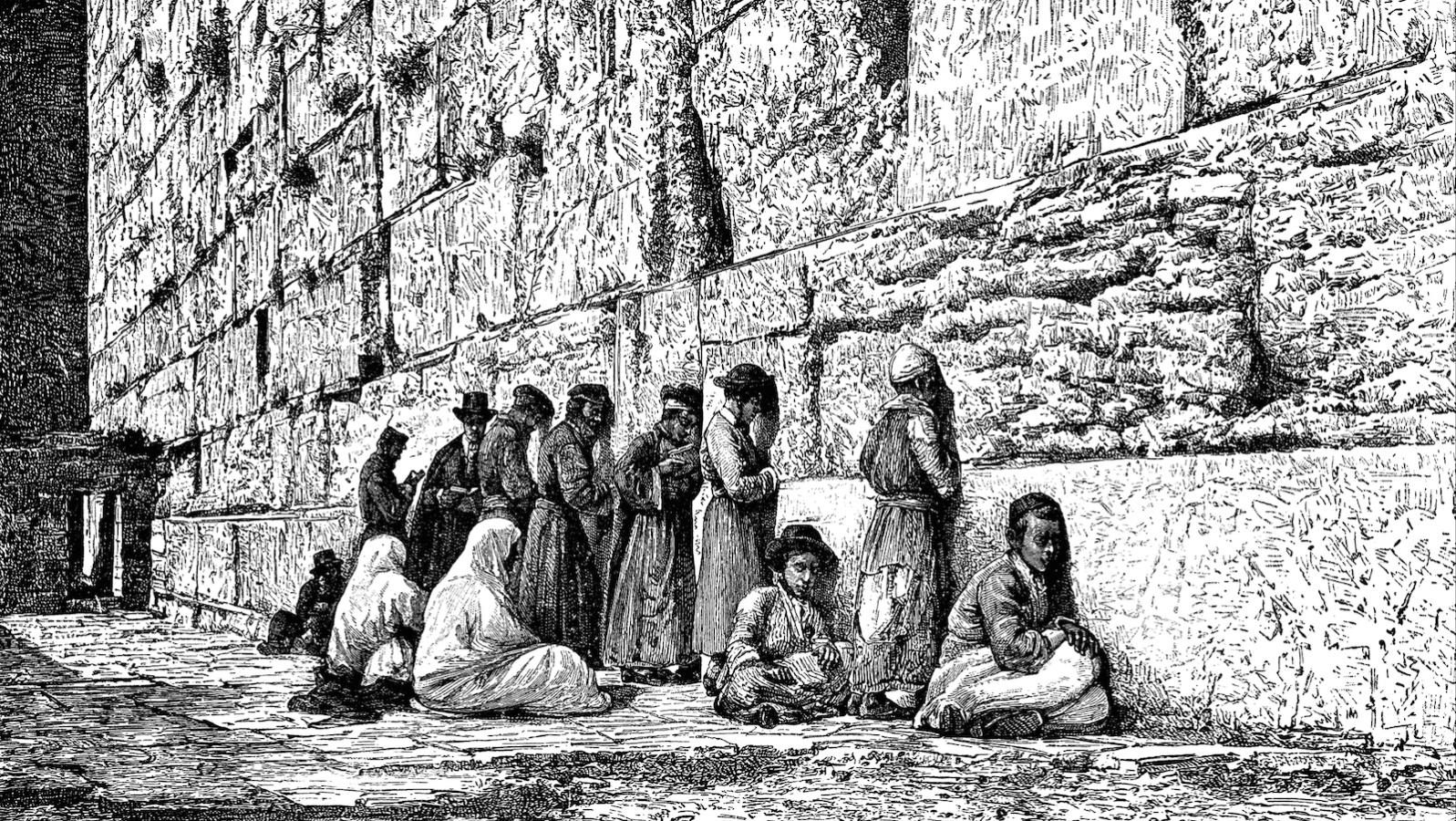

Stage Five: The Fast

For approximately 24 hours (adding on as is usual with Jewish sacred time), Jews act out total grief on Tisha B’Av. The symbolic acts draw from the rituals of a mourner sitting shiva, but the powerful paradigm is that of an overwhelmed defender of Jerusalem, now a Roman prisoner of war. From sundown to sundown, traditional Jews neither eat nor drink nor wash nor anoint themselves (recall the scenes of Jews in the Holocaust, kept sitting in the open squares all day without food or water). In the same spirit, they give up sexual relations that night. The story of the destruction is retold vividly by reading the Book of Lamentations. Unshaven, unwashed, hungry, people re-experience the tragedy of the Destruction.

Reprinted with permission of the author from The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays.

Av

Pronounced: ahv, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish month usually coinciding with July-August.

Sephardic

Pronounced: seh-FAR-dik, Origin: Hebrew, describing Jews descending from the Jews of Spain.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Tammuz

Pronounced: tah-MOOZ (oo as in boot), Origin: Hebrew, Jewish month that usually coincides with June or July.

halacha

Pronounced: hah-lah-KHAH or huh-LUKH-uh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish law.

shiva

Pronounced: SHI-vuh (short i), Origin: Hebrew, seven days of mourning after a funeral, when the mourner stays at home and observes various rituals.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Shehechiyanu

Pronounced: sheh-hekh-ee-YAH-new, Origin: Hebrew, a blessing said upon experiencing a new or special occasion.