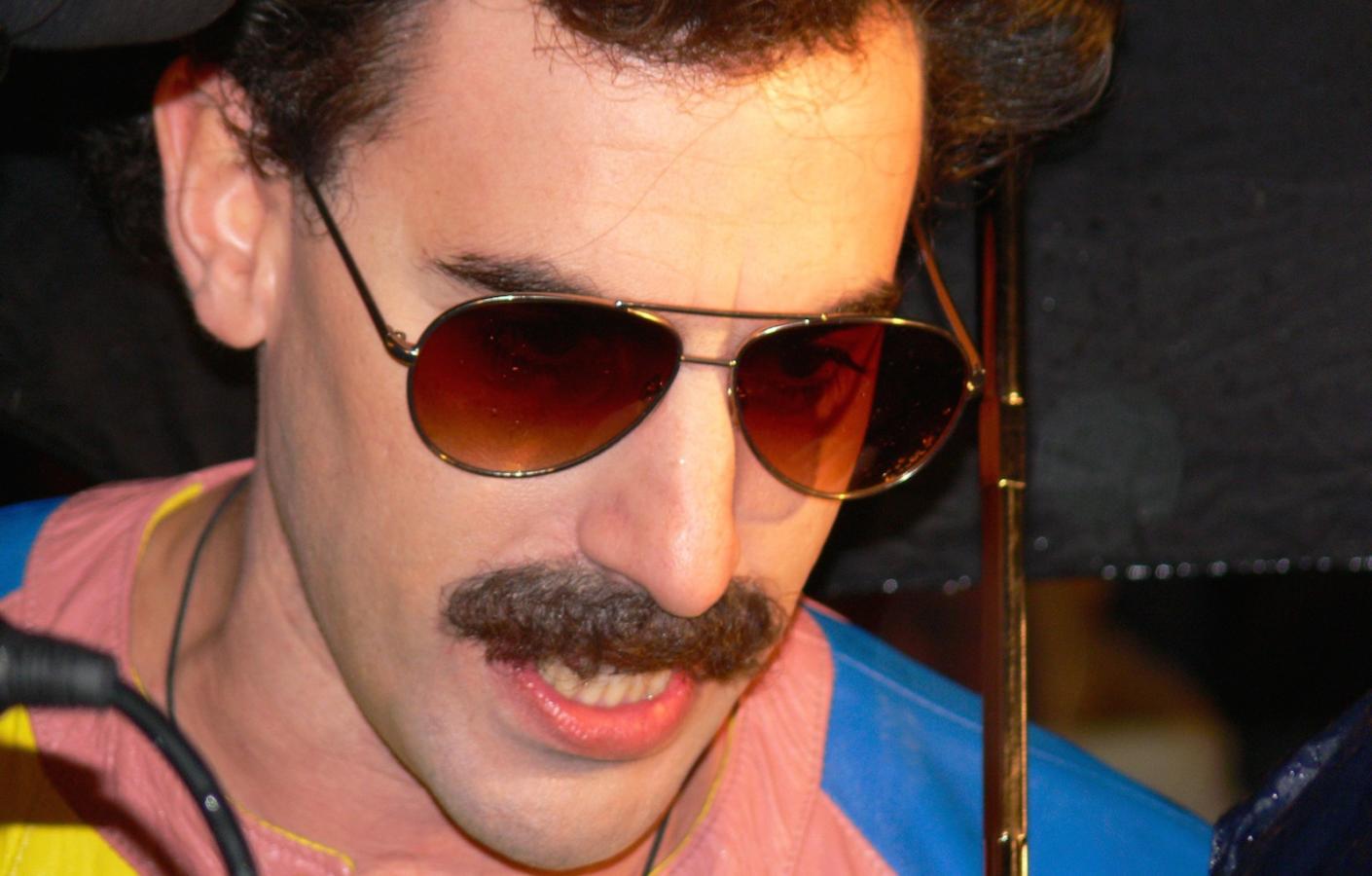

The British comic and cultural saboteur Sacha Baron Cohen first made his name in the U.S. as the host of HBO’s Da Ali G Show, an American version of his acclaimed U.K. program.

Note: This article was published in 2006. For more up-to-date information about Sacha Baron Cohen, visit our partner site JTA.

Cohen played a number of characters on Da Ali G Show, including the gay Austrian television host Bruno, hip-hop clown Ali G, and Kazakh journalist Borat Sagdiyev. Borat’s sketches usually revolved around absurdist interactions with clueless American heartlanders who believed Borat was filming a segment for Kazakh television. Under that guise, Borat/Cohen revealed misogyny, anti-Semitism, and assorted other forms of cultural stereotyping, and in turn, documented the absurdity, intellectual aridity, and closed-mindedness of a certain brand of American life.

From Kazakhstan to the Big Screen

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006), the full-length film spun out from Cohen’s Borat sketches, intends to be equal-opportunity offensive. But as it turns out, the bulk of the film’s humor is pointed in two directions: at Jews and at the homegrown American yahoos who agree with Borat’s cockamamie bigotry.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

At the beginning of the film, Borat Sagdiyev informs us that Kazakhstan is beset by three types of problems: the economic, the social, and the Jew. But before explaining these issues in greater detail, Borat gives his audience an impromptu tour of his hometown, Kusek. He introduces us to his portly, scowling wife, his sister–the #4 prostitute in all of Kazakhstan–and his rapist neighbor.

Borat’s Kazakhstan is a friendly place where the annual festival is dubbed the Running of the Jew, an extravaganza where participants flee, running-of-the-bulls style, from enormous puppet Jews–the man with hooked nose and flowing side-curls, the woman wielding a challah and a meat cleaver. When the female Jew pauses to lay an egg, the local children rush in, urged on by Borat: “Go kids! Crush that Jew egg before it hatches!”

American Road Trip

And then it’s on to America, where Borat and his producer Azamat (Ken Davitian) explore the strange byways of American life as they drive from New York to Los Angeles. They travel by car instead of plane, of course, just “in case the Jews repeat attacks of 9/11.” For Borat, and his countrymen, Jews are little more than a collection of their stereotypes, existing more as an all-purpose bogeyman than flesh-and-blood individuals.

Needing a place to stay one night, Borat and Azamat unknowingly stumble into a bed-and-breakfast run by a middle-aged Jewish couple. The joke is immediately clear to the audience (the man wears a kipah and the walls are covered with nostalgic paintings of Eastern European Jews), but it takes the two anti-Semites a few minutes before they realize where they are. Borat appears to go catatonic with shock, and as fright music plays on the soundtrack, he dutifully attempts to swallow the undoubtedly poisoned sandwich supplied by his hosts before mercifully spitting it out into his handkerchief. Borat records himself Blair Witch-style cowering in his bed, gripping a cross and a fistful of dollars to ward off the vengeful Jews while telling the camera “I’m in the nest of Jews…you can barely see their horns.”

Laughing at Anti-Semitism

Borat’s anti-Semitism is funny because it’s so comically ill-informed and because–for Americans and Jews–Kazakhstan is a relatively obscure country that lacks political and social resonance. If Borat were Iranian, his jibes about Jewish economic power might not be as funny. We laugh at Borat because we feel comfortable putting him in his place and because Cohen telegraphs to the audience that he is little more than a buffoon. We laugh at Borat because he is an anti-Semite, not in spite of it.

Nervous nellies, both Jewish and not, will likely find cause for concern in Borat, worrying that the film will inspire a newfound light-heartedness about anti-Semitism. They will raise the specter of Iranian nuclear ambition, of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s hideous aspersions about the Holocaust, of Hezbollah’s brazen attacks on Israel. And all of these are cause for deep concern. But they are not relevant to Borat, which renders anti-Semitism the province of the stupid and the backward.

For Borat, anti-Semitism is what grows in the Kazakh mud, remaining mostly unsuitable to American soil. It is the product of a lack of open discussion, of corruption, and of incompetent governments. Jews serve as an all-purpose scapegoat, a convenient explanation for all the world’s ills. Ahmadinejad might laugh at this film for different reasons than most Jews would, but he would quickly grasp that Borat is not much of a calling card for the anti-Semitic cause. There are many anti-Semites in the world to concern ourselves with, but Borat is not one of them.

Indeed, if we felt like Borat knew anything about Jews, expressing informed hatred rather than clueless cultural stereotyping or had any power regarding world affairs, it would be inordinately difficult to laugh at him. After all, former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed made headlines a few years back for making equally problematic anti-Semitic statements at a public forum, and just months before the release of Borat, Mel Gibson guaranteed his own infamy by drunkenly asserting that “Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world.” The difference between Mohamed, Gibson, and Borat, bluntly put, is that Mohamed and Gibson are culturally and politically significant individuals, and Borat is a hapless, impoverished drifter with a less than iron-clad grasp of television etiquette.

The other difference, of course, is that Borat is a practical joke, an absurd emanation from the brain of a British Jew. Nonetheless, the film asks us to juggle two equal and opposing notions–that Borat is a genuine Kazakh journalist and reflective of the values of certain anti-Semites (if not of his ostensible countrymen, as Kazakh government spokesmen would have it), and that Borat is merely a comic inversion of serious anti-Semites like Gibson and Mohamed

A Hollywood Ending

As with any endeavor of this type, there is always the danger of All in the Family syndrome setting in–the possibility that the film’s biggest fans will be those who get the joke least, celebrating Borat for the very qualities the movie mercilessly mocks. Even taking this into account, Borat, directed by Larry Charles and written by Cohen, Anthony Hines, Peter Baynham, and Dan Mazer, is one of the best American satires to emerge in many years.

Of course, in traditional Hollywood fashion, Borat is permanently changed by his journey, bringing back a taste of Hollywood to his native country. When we see him a few months later, he has replaced the traditional Running of the Jew with the far more palatable vision of a crucified Jew prodded repeatedly by villagers with pitchforks. As Borat knows all too well, some people never learn, and others (like Borat himself) learn their lessons all too well. In Borat’s case, the most famous religious film in recent memory provides inspiration for his revamped Jew-ritual. God bless you, Mr. Gibson!

challah

Pronounced: KHAH-luh, Origin: Hebrew, ceremonial bread eaten on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.