In 1895, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel founded the Nobel Prize, a set of annual awards given to individuals with world-class accomplishments in six categories: World Peace, Economics, Medicine, Chemistry, Literature and Physics. Since the establishment of this distinguished honor, about 20% of the recipients — over 200 individuals — have been Jewish. Famous Jewish Nobel laureates include Albert Einstein, Isaac Bashevis Singer and Bob Dylan. But many others did not become household names. Learn more about eight of these lesser-known renowned Jewish Nobel laureates.

1. Adolph Von Baeyer, Chemistry, 1905

In 1905, Adolph Von Baeyer became the first Jewish Nobel Prize winner. He is today considered a founder of modern organic chemistry, specifically recognized for his work with synthesized organic dyes. Before the mid-1800s, all dyes originated from natural sources such as plants, insects, roots and minerals. However, by the end of the century, dye manufacturing became a popular industry and booming business due to its commercial uses in clothing, textiles, paper and other miscellaneous items. Around this time, Baeyer discovered a way to industrially synthesize blue indigo dye, which was much less timely and expensive than extracting the organic compound naturally from plants. He also formulated its structure and elucidated the relationship between chemical composition and color. In addition to countless other accomplishments, Baeyer is also remembered for his Strain Theory which explains why molecules with carbon rings contain either five or six carbon atoms in each ring — because they are otherwise much less stable.

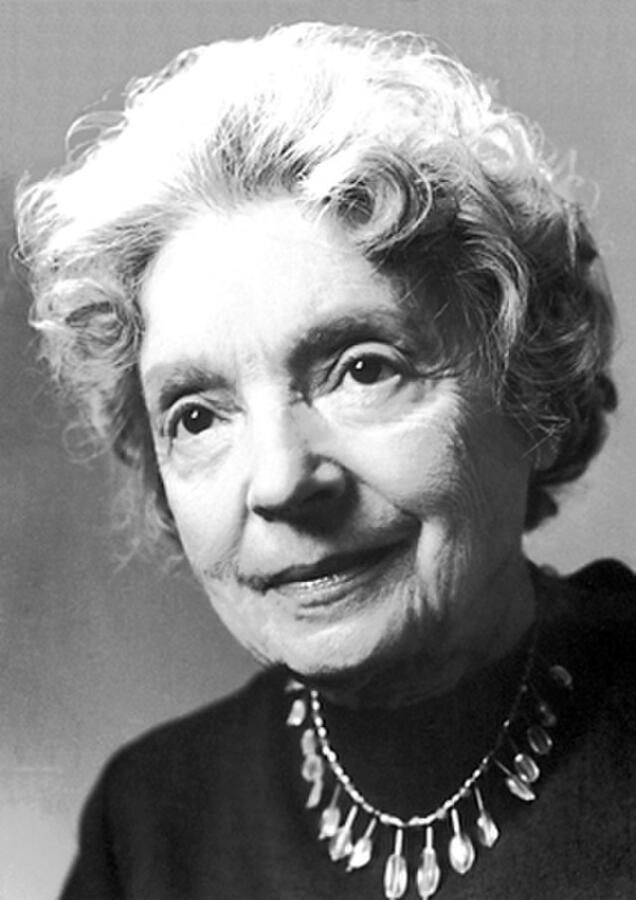

2. Gerty Cori, Medicine, 1947

Gerty Cori was the first Jewish woman to receive the Nobel Prize. Based at Washington University in St. Louis, Cori, along with her husband, studied the way the body metabolizes carbohydrates. They discovered a cyclical process in which glucose is converted to glycogen, which is used as stored energy, and when needed, glycogen is converted back to glucose to provide immediate energy to cells. In 1947, thanks to their work synthesizing glycogen in the laboratory and discovering the naturally occurring processes for metabolizing sugar, the Coris became laureates within the Medicine category.

3. Nelly Sachs, Literature, 1966

When Nelly Sachs was 15 years old, she became enamored with Gösta Berling, a novel by Swedish author and Nobel laureate Selma Lagerlöf. However, this author did so much more than inspire Sachs to pursue her dreams of writing; Selma Lagerlöf helped save Sachs’s life. After years of correspondence, Lagerlöf assisted Sachs and her mother in booking one of the last flights from Nazi Germany to Sweden at the start of World War II. Unfortunately, Sachs’s remaining family perished in the concentration camps.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Through her post-war poems and plays, Sachs acted as a spokesperson for the grief and hardships of the Jewish community while also inspiring hope, speaking of Israel’s destiny and reminding Jews of their intrinsic strength. Her acclaimed collections Sternverdunkelung (Eclipse of Stars), Undniemand weiss weiter (And No One Knows Where to Go) and Flucht und Verwandlung (Flight and Metamorphosis) are recognized for their powerful portrayals of the cycles of persecution, exile and suffering of the Jewish people. Many of Sachs’s works are translated to English from German, but her dramas were largely performed in her mother tongue.

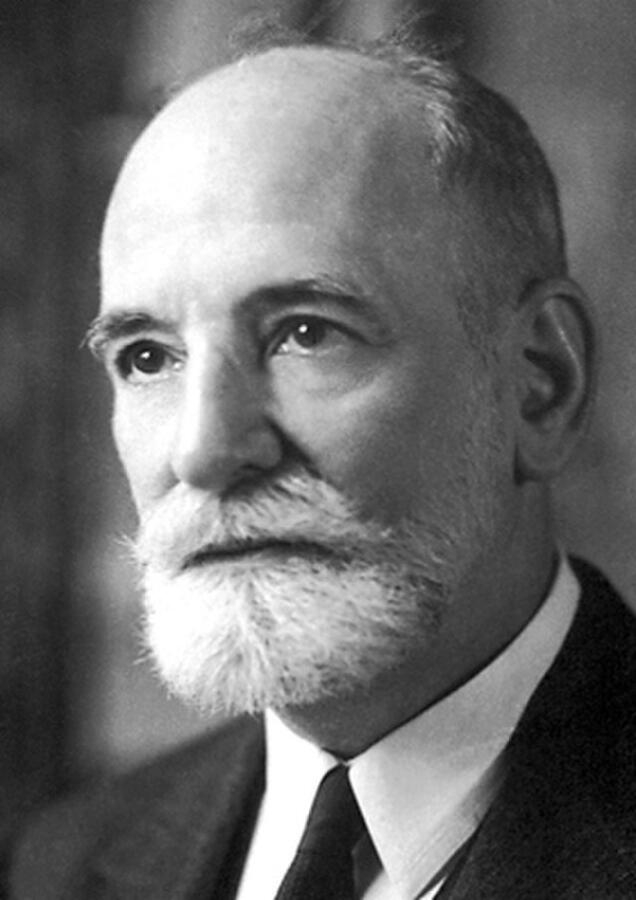

4. René Cassin, Peace, 1968

A humanitarian and jurist, René Cassin received the Nobel Peace prize in 1968 for co-authoring the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a landmark resolution adopted by the United Nations in 1948 that describes all human beings as having certain fundamental rights and freedoms.

Born in Bayonne, France to a Sephardic Jewish family, Cassin trained as a lawyer and then served in WWI, where he was seriously injured. Between the world wars, he became an advocate for disabled war veterans and worked as a pacifist and French delegate to the League of Nations, the first intergovernmental organization designed to maintain world peace. During the Second World War, Cassin served under General Charles de Gaulle in London, helping him to draft legal statutes to underpin Free France, the exiled French government. During this time, he addressed French Jews by radio, from London, exhorting them to join Free France forces.

After the war, in addition to co-authoring the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Cassin also served on the UN Human Rights Commission and the Hague Court of Arbitration. Beyond his work with the UN, he became a member and ultimately president of the European Court of Human Rights..

Throughout his career, René Cassin continued to prioritize aid to the Jewish community. After WWII, he became president of the French-Jewish Alliance Israelite Universelle, which has the purpose of protecting the rights of Jews and fighting discrimination. His legacy lives on through his creation of the Consultative Council of Jewish Organisation (CCJO) René Cassin, an NGO fighting antisemitism, genocide and discrimination.

5. Dennis Gabor, Physics, 1971

In 1971, Dennis Gabor was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing and inventing the holographic method which allowed for images to be created with the illusion of depth. Holographic 3D images have a plethora of significant and hobbyist uses today. Because they are difficult to forge, holograms are essential to many modern security systems including bank cards, passports and IDs. The technology also holds the potential to create unique data storage solutions, storing data in a dense, 3D format, something like a stack of incredibly thin pages. In his book Inventing The Future, Gabor declared, “the future cannot be predicted, but the futures can be invented.”

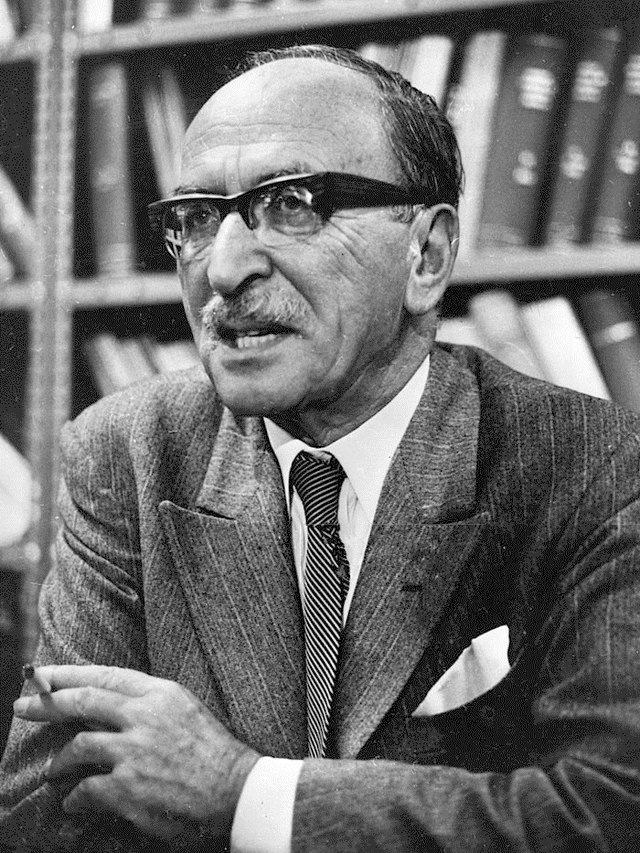

6. Wassily Leontief, Economics, 1973

Leontief was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he was arrested many times for openly opposing communism. In 1925, he was permitted to emigrate to the US, ultimately serving as an employee at the United States’s National Bureau of Economic Research and eventually a professor of Economics at Harvard University.

Wassily Leontief became a Nobel laureate in Economics in 1973 for his early contributions to the input-output method which analyzes and quantifies the interdependence between different sectors of the economy. He also used input-output analysis to investigate trade flow between the U.S. and other nations.

7. Martin Chalfie, Chemistry, 2008

In 2008, Martin Chalfie shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Osamu Shimomura and Roger Y. Tsien for their discovery of GFP, the green fluorescent protein. After studying biochemistry in Harvard and conducting research at Cambridge, Chalfie became one of the three leaders in the process of isolating the chemical produced by specific organisms that emit a bright green light. The construction of GFP is regulated by a gene that can be placed into the genomes of other types of organisms using genetic engineering. This operation can be effectively utilized to study biological processes by tracking specific cells with the green, fluorescent light. To Martin Chalfie, clearly the science was more important than the reward because he slept through the announcement of the winners!

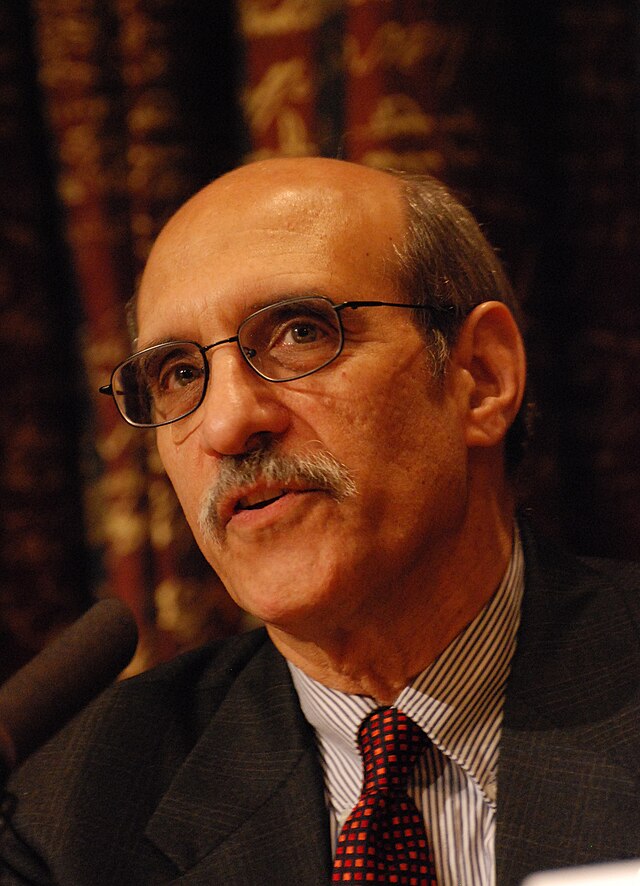

8. Michael Kremer, Economics, 2019

Michael Kremer, the son of Jewish immigrants from Austria and Poland, became a Nobel laureate in Economics in 2019 for his work alleviating global poverty. Working with Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, he conducted randomized controlled trials to test hypothetical anti-poverty measures. Rather than tackling the big picture of poverty with a one-size-fits-all method, his team focused on more manageable, smaller questions as they related to specific individuals and communities. After working many years in India and Kenya, Kremer and his colleagues showed that although hunger and a lack of learning materials and textbooks does have a negative role in students’ education, and supplying these resources can help, their education is particularly improved by targeting individual needs rather than broadly distributing the same resources to everyone. He found computer-assisted learning programs to be the most effective tool for addressing the individual needs of students.

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Kremer continued to use his resources to help underprivileged communities. He is the founder of WorldTeach, a Harvard-based organization that places college students and graduates in developing countries to educate civilians and children. Kremer also works as a research affiliate at Innovations for Poverty Action and is the co-founder of Precision Agriculture for Development, a non-profit organization that utilizes mobile phones as a tool for supplying agricultural services to smallholder farmers.