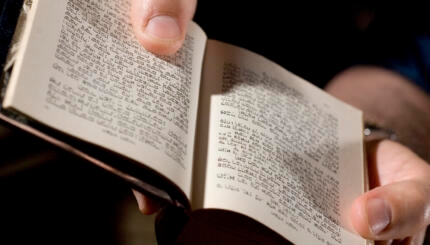

We created this ceremony to help us mourn and accept our inability to conceive a biological child, to share our disappointment with friends and family, and to enable us to move ahead with our lives after infertility. We have drawn from Jewish sources that deal with themes related to barrenness, death, bondage, freedom, and transitions.

We hope to counter the insensitivity found in traditional Jewish interpretations of childlessness as a test of faith, divine punishment, or grounds for a husband to divorce his wife. Individuals and couples who share our fate should try to personalize this service by telling about their own experiences and selecting materials that are meaningful to them. Creating the service together proved to be as healing to us as conducting it before a group of our friends and relatives.

Naming of the Ceremony

Seder means “the order (of the service).” Though kabbalat usually refers to the “welcoming” of Shabbat [Sabbath], it also connotes accepting, crying out against, and consoling. Ahkaroot means infertility or barrenness. Thus, Seder Kabbalat Ahkaroot signifies the order of rituals for crying out against, consoling ourselves about, and ultimately accepting the loss of our dream to have a biological child.

Opening of Ceremony and Tashlich

With meditative music in the background, the guests read an explanation of why we chose to create the service. Then they listened to a part of Bonnie Raitt’s song, “Nick of Time,” which deals with delayed parenthood and the aging process. The first reading was the passage about Hannah‘s infertility from I Samuel: 1-10, which ends with: “And she was in bitterness of soul and prayed to the Lord and wept in anguish.” We jointly responded:

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

We, too, have wept and felt the anguish of Elkanah and Hannah, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Rachel, the moment they feared they might never have children. We are haunted by the cry of Rachel to Jacob: ‘Give me children or I shall die.’ (Genesis 30:1)

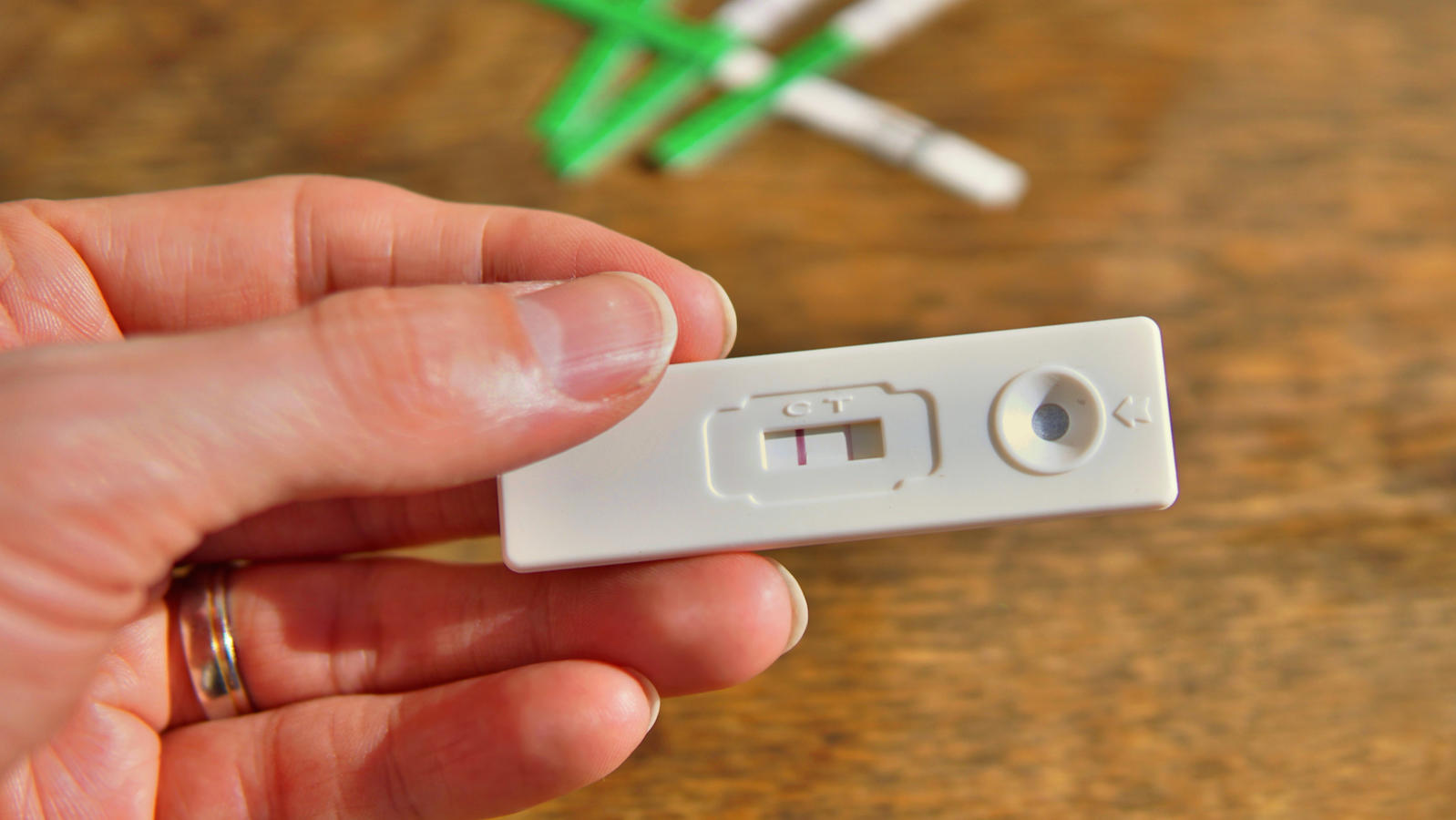

We spoke of the emotional pain caused by infertility. We noted how in modern times faith in medical miracles has replaced faith in God as a cure for infertility, but added that dependence on high-tech procedures can become an obsession, which we illustrated with a poem about contemplating continuing infertility treatment after too many failures (Margaret Rampton Munk, “Mother’s Day,” Without Child: Experiencing and Resolving Infertility, pp. 162-163).

After everyone read from Ecclesiastes 3:5, ending with the line, “A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing,” we jointly declared:

Our time to plant has ended; our time to mourn has begun; we must weep before we can laugh. In the recesses of our minds, however, there still lingers a thought that it might have worked the next time. Therefore, we need to cast away our regrets and ‘what ifs’ into the ocean like the symbolic sins we throw into the water on Rosh Hashanah to begin the year with a clean slate [the Tashlich ceremony]. To paraphrase the prophet Micah, ‘God will have compassion on us. We will cast all our qualms and dim hopes into the depths of the sea.’ (Micah 6:19)

We crumbled some bread in our hands and threw it into the water.

The Memorial Service

We mourned the death of our dream by performing a kriah ritual [the traditional tearing of one’s clothing, or a black ribbon, after the death of a close relative], but instead of cutting a black ribbon, we cut and wore blue and pink ribbons because we will never know what the gender of our baby would have been. Next we read a prayer originally written to memorialize a miscarriage:

May the One who shares sorrow with Your creation be with us now as we experience the loss of potential life. We are sad as we think of our hopes for this unborn one, as in our minds we imagine what might have been.

Life is a fabric of different emotions and experiences. Now, while we experience life’s bitterness and pain, be with us and sustain us. Help us to gather strength from within ourselves, from each other, and from our friends.

Blessed Are You, O Divine Presence, Who shares sorrow with Your Creation.(Rebecca T. Alpert, The Reconstructionist, Sept. 1985, p. 4)

Following this, everyone joined us in the recitation of the Kaddish [memorial prayer in praise of God] in both Hebrew and English.

The Seder of Condolence

We explained the traditional significance of the following foods eaten at the shiva meal after a funeral, the Passover seder, and Rosh Hashanah: hard-boiled eggs symbolizing the lifecycle, bread symbolizing the staff of life, salt-water symbolizing the tears of our despair, horseradish symbolizing the bitterness of failure, honey symbolizing the sweetness of liberation from infertility, and wine symbolizing joy.

We listed the 10 plagues of our infertility, taking a drop of wine out of the cup for each one: denial, anger, shame, marital stress, isolation from and envy of friends who have biological children, reproductive regimentation, uncompensated medical costs, depression, loss of control, and death of the dream of the firstborn.

We dipped the egg into the water and ate it to remember the tears we shed over the two miscarriages we experienced. We made and ate a sandwich of horseradish, honey, and bread to signify how a bitter ending may precede a sweet beginning and that happiness and sadness are part of human existence. Everyone said the traditional blessings over maror [bitter herbs] and bread.

We ended the seder with a responsive reading of a new Rosh Hashanah prayer about the qualities we hope God will help us develop in response to various life crises. For example, “If we must face sorrow, help us to learn sympathy (“To Face the Future,” A Tapestry of Prayer).”

Shehechiyanu and Havdalah

Everyone recited the Shehechiyanu, which thanks God “for sustaining us, and for enabling us to reach this season.” We explained that our Havdalah [service that separates the Sabbath or a holiday from the weekday] separates the dark years of our infertility from the upcoming lighter years when we will either adopt or choose to be child-free. We read a passage about no longer considering ourselves infertile because from now on, we would define our lives according to what we do and can have, rather than according to what we don’t have. (Jean W. Carter and Michael Carter, Sweet Grapes: How to Stop Being Infertile and Start Living Again, pp. 14-15)

We performed the Havdalah service, lighting the double braided candle and declaring:

We must distinguish between the heartbreak of infertility and the joy of transcending it. We must separate our pain and grief from the new generative opportunities that lie ahead of us.

We raised the cup of wine and everyone said the blessing over it. We held up the spice-box and smelled the spices to invigorate the new spirit we now possess as we look to the future. Then everyone sniffed it and said the blessing over it. Everyone recited the blessing over fire and the final Havdalah blessing as the candle was extinguished in a full cup of wine that overflowed like the full life we hope to lead.

Conclusion of Ceremony

We confessed that our struggle with infertility initially had strained, but subsequently had strengthened our marriage. In this regard, we read a Midrash [biblical interpretation] that tells the story of a man who planned to divorce his childless wife. His rabbi commanded him to throw a party to celebrate the divorce. At the party, the man told his wife to keep whatever item in his house was most precious to her. After he drank too much wine and fell asleep, his wife ordered her servants to carry him to her father’s house. When he awoke, she told him that he was the most precious thing to her. Moved by her love, he remained married to her. (Song of Songs Rabbah 1:4)

We related how people always ask whether we have a family. We now reply by telling them, “Yes, we have each other! If we have learned anything from this ordeal, it is that love is far greater than reproduction.” We removed the kriah ribbons and replaced them with red rose corsages. Then we played Debbie Friedman‘s, “Arise My Love,” whose lyrics are from the Song of Songs 2:10-13. The guests shared relevant readings or their own personal thoughts after the service.

Reprinted by permission of the author from A Ceremonies Sampler (Woman’s Institute for Continuing Jewish Education), edited by Elizabeth Resnick Levine.

Havdalah

Pronounced: hahv-DAHL-uh, Origin: Hebrew, From the root for "to separate," the ceremony marking the end of Shabbat and the beginning of the week.

Rosh Hashanah

Pronounced: roshe hah-SHAH-nah, also roshe ha-shah-NAH, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish new year.

seder

Pronounced: SAY-der, Origin: Hebrew, literally "order"; usually used to describe the ceremonial meal and telling of the Passover story on the first two nights of Passover. (In Israel, Jews have a seder only on the first night of Passover.)

kriah

Pronounced: KREE-yuh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish mourning custom of tearing one's garment.

Tashlich

Pronounced: TAHSH-likh (short i), Origin: Hebrew, literally “cast away,” tashlich is a ceremony observed on the afternoon of the first day of Rosh Hashanah, in which sins are symbolically cast away into a natural body of water. The term and custom are derived from a verse in the Book of Micah (7:19).

Kaddish

Pronounced: KAH-dish, Origin: Hebrew, usually referring to the Mourner's Kaddish, the Jewish prayer recited in memory of the dead.

shiva

Pronounced: SHI-vuh (short i), Origin: Hebrew, seven days of mourning after a funeral, when the mourner stays at home and observes various rituals.

Shehechiyanu

Pronounced: sheh-hekh-ee-YAH-new, Origin: Hebrew, a blessing said upon experiencing a new or special occasion.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.