Commentary on Parashat Shoftim, Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9

- Laws regarding both sacred and secular legislation are addressed. The Israelites are told that in every dealing they should pursue justice in order to merit the land that God is giving them. (16:18–18:8) The people are warned to avoid sorcery and witchcraft, the abhorrent practices of their idolatrous neighbors. (18:9–22) God tells them that should an Israelite unintentionally kill another, he may take sanctuary in any of three designated cities of refuge. (19:1–13) Laws to be followed during times of peace and times of war are set forth. (19:14–21:9)

Focal Point

You must be wholehearted with Adonai your God (Deuteronomy 18:13).

Your Guide

In Genesis 6:9 and 17:1, the Hebrew word tamim is used to refer to Noah and Abraham, respectively, and is translated as blameless. In Deuteronomy 18:13, the same word, tamim, is translated as wholehearted. Why is this word translated differently in our portion?

What does being wholehearted mean? Does it mean the same to you as being blameless?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Rabbinic commentators have written that only five biblical verses convey the essence of Judaism and this is one of them. Why do you think that they felt this verse is so important?

Deuteronomy 18:13 appears in a section that enumerates the abhorrent practices of sorcery and witchcraft. Does this knowledge affect how you understand the verse?

By the Way…

That, I believe, was what God asked of Abraham. Not “Be perfect,” not “Don’t ever make a mistake,” but “Be whole.” To be whole before God means to stand before Him with all our faults as well as our virtues and to hear the message of our acceptability.… Know what is good and what is evil, and when you do wrong, realize that that was not the essential you. It was because the challenge of being human is so great that no one gets it right every time. God asks no more of us than that (Harold S. Kushner, How Good Do We Have to Be? p. 180).

To be sure, they seek Me daily, as though eager to learn My ways. Like a nation that does what is right, that has not abandoned the laws of its God.… “Why, when we fasted, did You not see? When we starved our bodies, did You pay no heed?” Because on your fast day you see to your business and oppress all your laborers! (Isaiah 58:2–3).

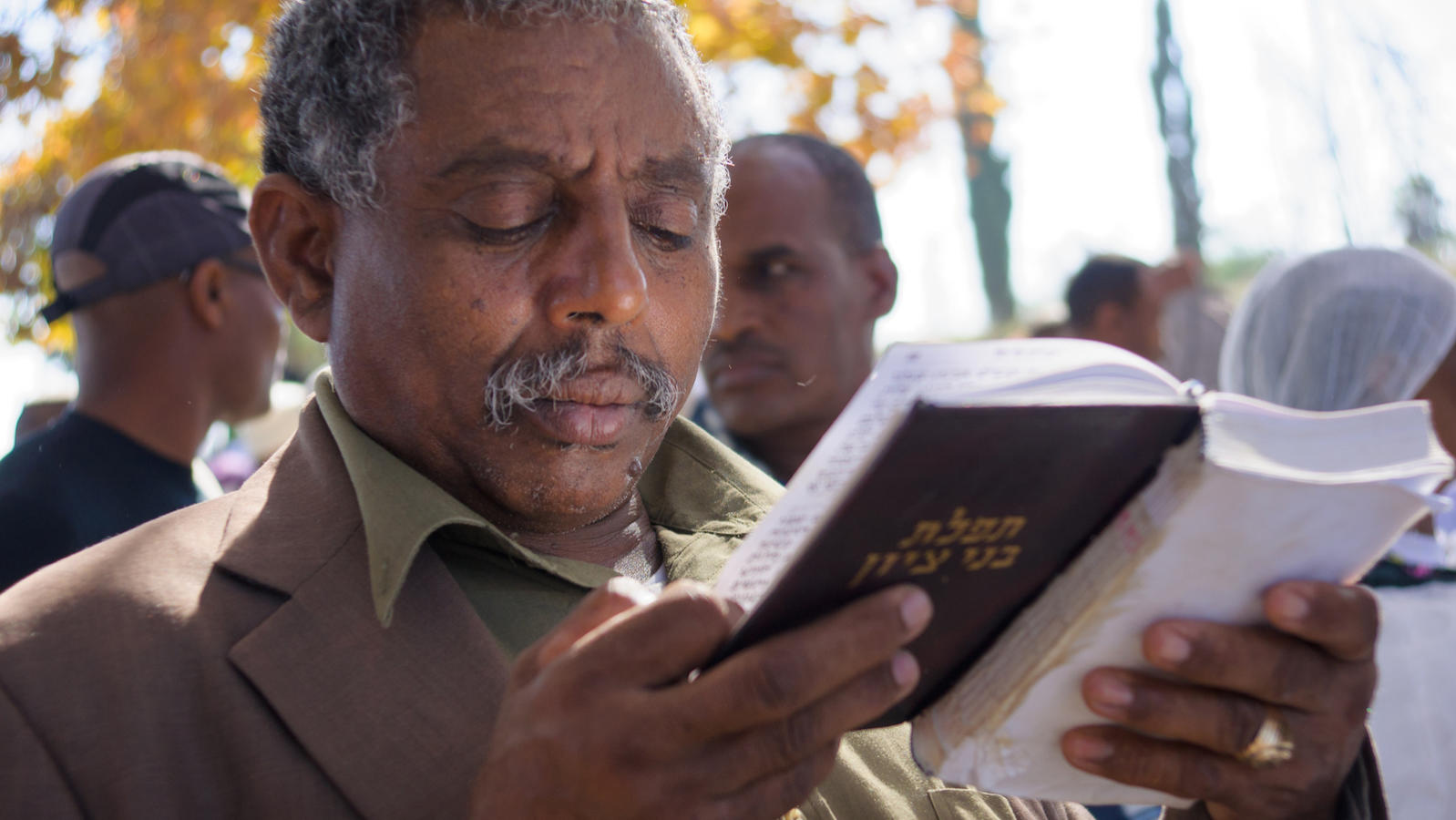

Classical Jewish ethicists have attempted to illuminate the difficulty and significance of being wholehearted. “For you must know that words are a matter of the tongue, but meaning is a matter of the heart…. When a man prays only with the tongue, the heart is preoccupied with something other than the meaning of the prayer…. The prayer becomes like a body without a soul, a shell without contents.… Only the body is present; the heart is absent” (Bahya Ibn Pakuda quoted in The Book of Direction to the Duties of the Heart by Menahem Mansoor, p. 365) .

Your Guide

If Rabbi Kushner is suggesting that we need not be blameless but only wholehearted, does he mean that all we have to do is try our best? Is this enough for us? Is this enough for God? Is this what is intended in Deuteronomy 18:13?

What exactly bothers Isaiah? Is he simply railing against hypocrisy? Is he perhaps worried about a deeper issue, such as the compartmentalization exemplified by President Clinton’s behavior in that he was able to act with caution and restraint in matters of state but not in his personal life? Is there a connection between Isaiah and the modern concept of compartmentalization?

In the 19th-century Lithuanian yeshivah founded by Rabbi Israel Salanter, the students were required not only to study Torah and Talmud but also to undergo an examination of their ethics and character. They were supervised by an ethical mashgiach (supervisor) who examined the students closely for blemishes in their character and behavior. Is it possible that our hearts will never be whole for God unless we are willing to carefully examine the blemishes and defects that make us “un-kosher?”

D’var Torah

There is no doubt that Deuteronomy 18:13 is a very important verse. At times it is either neglected or underrated because it appears in a portion that includes many significant rules and admonitions pertaining to justice, war crimes, conscientious objection, and protection of the environment. And as if that were not enough, in Shoftim we also find the famous phrase “Justice, justice shall you pursue” (Deuteronomy 16:20), which is always worthy of serious study and discussion.

I believe that there is a reason why being wholehearted appears in this week’s portion. Perhaps Deuteronomy 18:13 will lead us to justice. And since this verse is viewed as one of the five great biblical passages, it possesses the power to be both timely and timeless.

The purpose of this verse may be to remind us that at times we approach God with an insincere heart, a heart that is neither whole nor full. Accordingly, we create a distance between ourselves and God. We erect barriers and obstacles that keep us far away from God. Is it our behavior alone that stops us from being wholehearted? Our behavior is indeed part of the problem, but it is not the entire problem.

Maybe we cannot be holy because we are not wholly for God: We only give and show part of ourselves to God. We are plagued by a disharmony that prevents us from connecting our hearts, words, and deeds to create a beautiful tapestry that is prosaic as well as Mosaic.

In essence, you cannot be wholehearted for God when your heart is reserved for another God or when you are unwilling to give any of your heart to God. A heart that belongs only to you and cares only for you is not a heart that can be whole for God.

Provided by the Union for Reform Judaism, the central body of Reform Judaism in North America.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.