For the Israelites, the holiday of Shavuot was the culmination of the process of transcending innate, animal nature to liberate the human being. As we learn at Passover, the release from physical bondage alone is not freedom. True freedom is knowing what you want to do — what you truly want being what is good for both the body and soul — and having the discipline to achieve it, which means being able to control the natural desire for immediate gratification that can distract you.

To learn how to count the Omer, click here!

The period that connects the two levels of freedom, Sefirat Haomer (counting of the Omer), began with the cutting of the first sheaf of barley that ripened. Barley is animal fodder. An animal is a being whose consciousness consists of the immediate situation. Having no vision of what is beyond the self is the least Jewish of attitudes. As we count the days representing the duration of the barley harvest, we rise toward the start of what was the wheat harvest. Wheat is human food, a symbol of hokhmah, intelligence (based on the rabbis’ dictum that a child does not utter its first word until it has tasted bread).

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The offering brought to the Temple at the start of the Omer was meal ground from the barley grain, a raw material representing the first step in the production of leavened bread, which was the offering at the end of the Omer, on Shavuot. The message is that without Torah, which gives us the insights to recognize what we want, and the moral standards and social ethics to guide us to accomplish it, we are like animals who respond to instinct. Raw barley needs to give way to the refined wheat, the grain to meal and bread. Raw natural intelligence needs to be refined to become the wisdom through which potential can be reached. Once our animal selves, which are always present, are under control, we are ready to learn how to get the most out of life.

That is why counting the Omer continued even after the development of a standard calendar eliminated its initial necessity: to let the majority of people — farmers occupied with field work — know exactly when to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem. It remained an opportunity to help us move out of enslaving patterns of thought and behavior. For the ancient Israelites, each day was a step away from the defilement of Egypt and a step toward spiritual purity. Like the Israelites who began to get ready for their encounter at Mount Sinai as soon as they crossed the Reed [or Red] Sea , we use the seven weeks beginning on Passover to similarly prepare ourselves for the arrival of Shavuot. During this time, we are supposed to evaluate our behavior and work to improve ourselves, particularly by being more faithful to God and dedicated to His ways, more humble, and unified with all other Jews (Exodus 19:2).

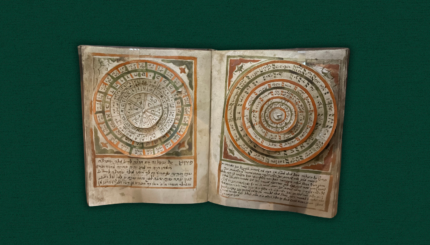

The sages devised a construct to help us follow in the Israelites’ footsteps. It is based on seven Divine qualities in the kabbalistic design of the universe, which were represented by the illustrious leaders of Israel (in one variation): love (Abraham), respect (Isaac), compassion (Jacob), efficiency (Moses), beauty (Aaron), loyalty (Joseph), and leadership (David).

These virtues, in their extreme, become vices (lust, fear, indulgence, obsessiveness, vanity, submissiveness, and stubbornness) that we have to strive to avoid. So the sages dedicated each week of the Omer to one of the characteristics and each day of the week to one of them. The unique combination on each of the 49 days (love-love, love-respect, love-compassion… respect-love, respect-leadership, and so on) helps us gain insight into our own behavior in relation to them, and focus our efforts on self-improvement, to make each day of the Omer important.

Torah study in general is customary and appropriate. Some people read portions from every book of the Bible, and review of the Ten Commandments is common. Many read Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), a particularly accessible section of Talmud. Study culminates in the Tikkun Leil Shavuot [all-night studying on the first evening of Shavuot], meant to make up for omissions or deficiencies in our devotion to Torah during the preceding year. It helps us to be particularly receptive to the body of law we will be given the next morning.

Excerpted from Celebrate! The Complete Jewish Holiday Handbook. Reprinted with permission from Jason Aronson Inc.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.