Whether you heard it in “Spaceballs” or learned it in Hebrew school, “Let my people go” has been the catchphrase of the Exodus story for a long time. It has drama — the small Moses facing the big Pharaoh. It has impact — the strong imperative. And it has brevity — it is clear and to-the-point.

There’s only one problem: Moses never says “Let My people go,” because that’s not what God asks him to say. Instead, God instructs Moses to tell Pharaoh: “The LORD, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, ‘Let My people go that they may worship Me in the wilderness.’” (Exodus 7:16).

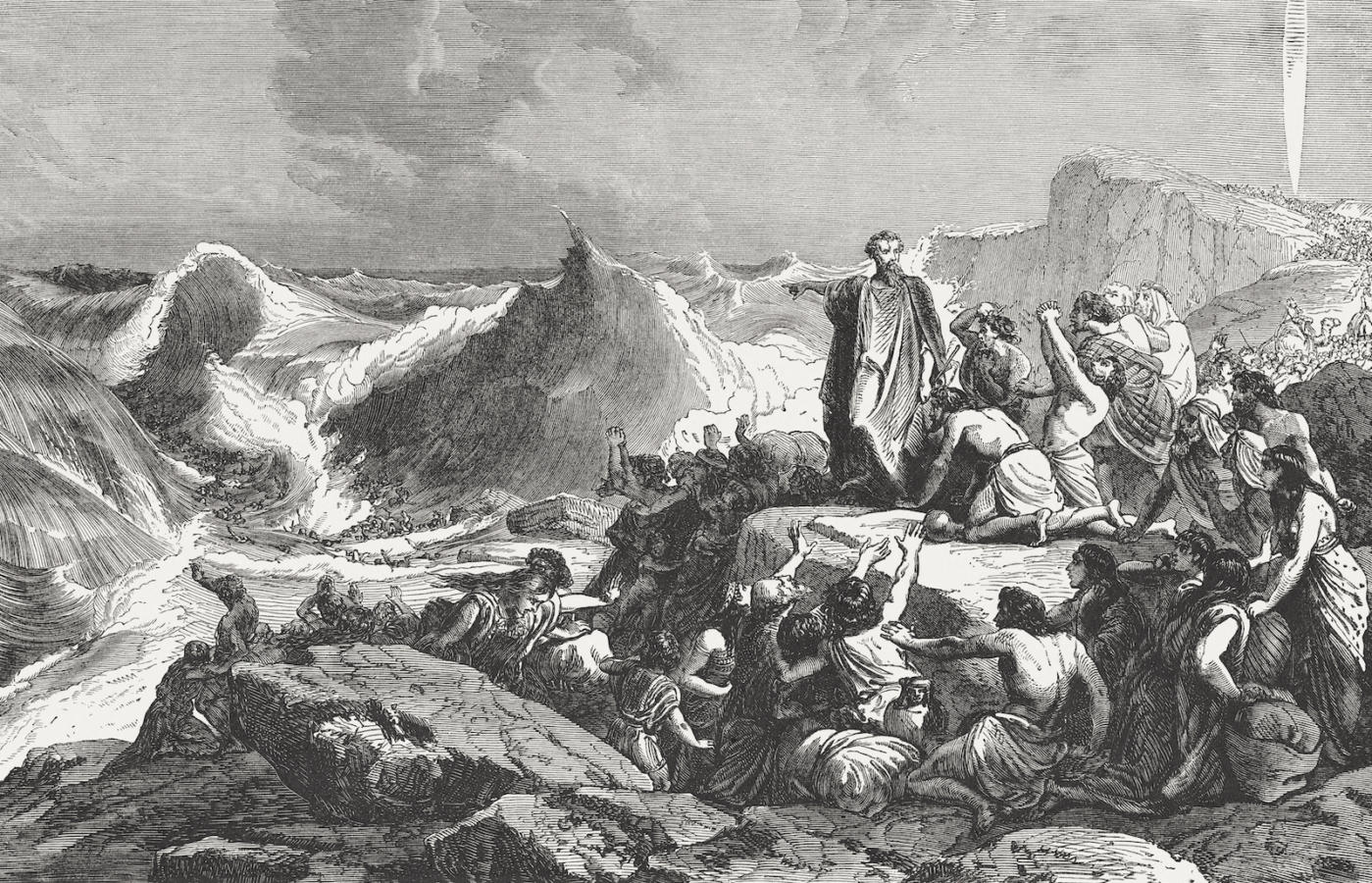

Now, imagine that you are an Israelite on the far shores of the Red Sea. You have crossed, miraculously, through a crashing sea and arrived on dry land. Surrounded by sounds of jubilation, drums and singing and dancing, you are free. But, what now? Where do you go? What do you do? What does it mean to be free, unguarded and unsure in an unknown wilderness?

In the children’s book No Rules for Michael, the protagonist blurts out that he doesn’t like rules; life is more fun, he says, without them. In a wonderful moment of emergent curriculum, his teacher lets the students explore this with a rules-free day at school. No one needs to take turns on the swings or divide the snack evenly. No one needs to let someone else talk or put away their backpacks.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

It turns out to be a pretty miserable day for Michael and his friends, and they are happy to return to their normal routines—rules and all. The moral, of course, is that sometimes rules are there to help us, to protect us and guide us towards good behavior and healthy relationships.

When the tablets of the Ten Commandments are given, they are the first rules we encounter in the wilderness, the first boundaries within this new freedom. The Torah tells us that the tablets were God’s work. More specifically, the text wants us to imagine that “the writing was God’s writing, engraved on the tablets.” Exodus 32:16

In a bit of rabbinic wordplay, the rabbis suggest that we not read charut (“engraved”), but rather cheirut (“‘freedom”). God’s freedom, they say, is engraved on the tablets. And what is God’s freedom? That no one is truly free except the one who is busy with the study of Torah. Avot 6:2

The Jewish conception of freedom is not a wild one. It is not an unbounded, do-whatever-you-want kind of place. Rather, the Exodus from Egypt defines for us a different sort of freedom.

Let my people go that they may serve me, God says. Let them serve higher ideals and a prophetic vision. Let them serve humanity and better the reality of the world. Let them serve their best selves, and something far beyond themselves.

We spend much of the Passover night celebrating our freedom from: from slavery, from Egypt, from darkness. But it’s also important to think about what our freedom from gives us freedom to: to be, to do, to believe.

Rabbi Sarah Wolf writes:

If we take the Exodus narrative seriously, we have been liberated in order to serve God, so we might consider how, exactly, we’re meant to do that. Serving God means, among other things, that we align our choices and behavior with righteousness, voluntarily submitting our own desires to a greater good.

As Rabbi Yitz Greenberg explains, “Freedom means freely choosing commitment and obligations that bring out the individual’s humanity. What are those obligations that each of us can make that bring out our humanity and give our lives meaning?”

Together, we come out of Egypt on the night of the Passover Seder. If we do it with the right intentions and the right mindset, our journeys to liberation can show us the beauty in a freedom with limits — the bounded freedom of relationship, of belief, and of service to something greater than ourselves.