The concept of an ideal or heavenly Jerusalem appears to emerge in Jewish tradition in the third century of the Common Era. There is a midrash, a rabbinic homily, in the name of Rabbi Yochanan, a leading rabbinic figure in Tiberias in the early third century, who asserts, in part, that in the future the earthly and the heavenly Jerusalem will be reunited as one. This teaching is based on an exposition of Psalms 122:3, “Jerusalem built up, a city knit together.” According to the midrash, ‘knit together’ means the uniting of the earthly Jerusalem with the heavenly Jerusalem as one. However, the roots of this idea are found in earlier Jewish thinking.

Today, it is difficult for us to comprehend the impact on the Jewish people and on Jewish life of the conquest and destruction of the Temple and the city of Jerusalem by the Romans in the year 70 C.E. In the minds of the Jewish leaders of that era, the Rabbis, it was the worst tragedy ever in the history of the Jewish people.

Both in national and religious terms, it appeared that Jewish life might come to an end. The Temple, the physical link between God and the Jewish people, and its rituals and rites, abruptly ended. The city of Jerusalem lay in ruins and Jews were forbidden to live within its walls. Moreover, the Romans continued their occupation of the land of Israel and their oppression of the Jewish people. Uprisings against Rome were brutally crushed in both the early and the middle of the second century. Following these failed revolts, it was clear to the Rabbis that revolt against Rome was futile.

Therefore, the Temple would not be restored any time soon, nor would Jerusalem return to her former glory. With the earthly Jerusalem in ruins, it is easy to understand why Jews would want to imagine a heavenly Jerusalem existing in all its glory.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Influence of Greek Philosophy

Another factor contributing to the development of the concept of a heavenly Jerusalem is the philosophy of Plato, as it was understood then. Platonic thought posits that every real object draws its existence from an ideal metaphysical form. Thus, if there is a Temple on earth, there must be a metaphysical Temple; an earthly Jerusalem demands a heavenly Jerusalem. Rabbinic thought is full of metaphors, images, principles and the like that have their origins in Greek philosophy. It is understandable that, eventually, the loss of the earthly Jerusalem would be mitigated by belief in a perfect heavenly Jerusalem. In fact, belief in the heavenly Jerusalem became so entrenched, that the rabbinic mind imagined that Jerusalem had been created by God at the beginning of the universe.

Heavenly Jerusalem in Rabbinic Literature

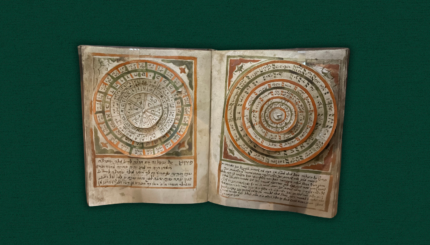

The midrashic literature from the second century on is filled with descriptions of the rebuilt Jerusalem of the future. Various Midrash texts describe its dimensions, the materials of which it will be built, and the regard in which it will be held in terms that can only be categorized as fantastic. The rabbinic imagination is unbridled as it contemplates the restored and rebuilt Jerusalem of the future. It is only a tiny further step for these fantasies to take the form of a heavenly Jerusalem.

The midrash in which Rabbi Yochanan is cited raises the question as to whether the heavenly Jerusalem is simply a template or mirror image of the earthly Jerusalem or a reality unto itself that one day will materialize on earth. From the context, it can be assumed that one rabbi believed that the heavenly Jerusalem exists intact regardless of the state of the earthly Jerusalem. Rabbi Yochanan seems to argue that only when the earthly Jerusalem is restored fully that the heavenly Jerusalem will be realized fully as well. The rabbinic concept of an ideal Jerusalem existing in the heavens fuels much speculation in later generations in Jewish history.

In Medieval Times

During the middle ages, the most passionate Jewish movements that embraced the idea of the heavenly Jerusalem were often disappointed by the reality. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, Jews were able to live in Jerusalem again. And though Jerusalem was no longer a significant commercial or political center, Jews lived in Jerusalem for historical and spiritual reasons. However, for centuries Jews did not migrate from the major centers of Jewish population in the Islamic world to Jerusalem. It was only with the Crusades that Jews from Europe realized that it might be possible to live in the land of Israel, perhaps in Jerusalem itself.

One of the leading rabbinic figures of Spain, Rabbi Moses ben Nachman, called Nachmanides, was forced to leave Spain in the middle of the 13th century. Although considered by many scholars to be a Jewish rationalist, his commentary on the Torah reveals a strong mystical orientation. When he eventually reached Jerusalem and found it largely in ruins with a very small, impoverished Jewish community, he wrote of his dismay and disappointment. Clearly, the ideal Jerusalem that he imagined he did not find in the Jerusalem on earth of his day.

From the Mystics to the Hasidim

In the 16th century, a community of mystic Jews migrated from Germany to the land of Israel. Settling in the city of Safed in northern Israel because it was more closely tied to Jewish mystics in the land of Israel, this community developed a practical mystical philosophy that would give new meaning to the idea of a heavenly Jerusalem. The leader of this community, Rabbi Isaac Luria, taught a doctrine that explained how the world could be restored to perfection through human action. He explained that in creating the world, God first created vessels to contain the divine light that give the world life. However, the vessels were not strong enough and the divine light shattered the vessels. Thus, the sparks of divine light and the shards of the broken vessels become intermixed.

The task of human beings is to gather the divine sparks, one by one, until all have been collected. As this teaching began to take hold, it provided a means by which the ordinary Jew could help to build the heavenly Jerusalem. For only when the heavenly Jerusalem was fully built, could it become manifest on earth.

A couple of centuries after Rabbi Luria, a new movement arose in Eastern Europe, Hasidism. The Hasidim embraced the teachings of Rabbi Luria and added some elements of their own. Hasidism, generally speaking, believes that ordinary Jews can bring the messianic age by serving God in joy and by observing various precepts of Jewish tradition more fully. With regard to the idea of a heavenly Jerusalem, various Hasidic teachers believed that Jews could build the heavenly Jerusalem through actions and deeds. The Ropshitzer Rebbe, for example, taught, “By our service to God, we build Jerusalem daily. One of us adds a row, another only a brick. When Jerusalem is completed, redemption will come.” This saying attests to the power and durability of the idea of a heavenly Jerusalem over the centuries. For Jews who never saw the earthly Jerusalem, the heavenly Jerusalem inspired and sustained their faith.

Heavenly Jerusalem Today

The emergence of the State of Israel in our days, and the recapture and reunification of the earthly Jerusalem in the Six Day War in 1967, has for some Jews brought the heavenly and earthly Jerusalem together. However, for Jews who believe in the divine messianic redemption of the world, modern Jerusalem is still just a shadow of the Jerusalem that will exist in the future. Obviously, for them the heavenly Jerusalem is not yet completed, or the era of the messianic redemption would have arrived. For most Jews today, however, the achievements of the State of Israel in unifying and expanding modern Jerusalem is the fulfillment of the dreams and prayers of almost two millennia.

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.