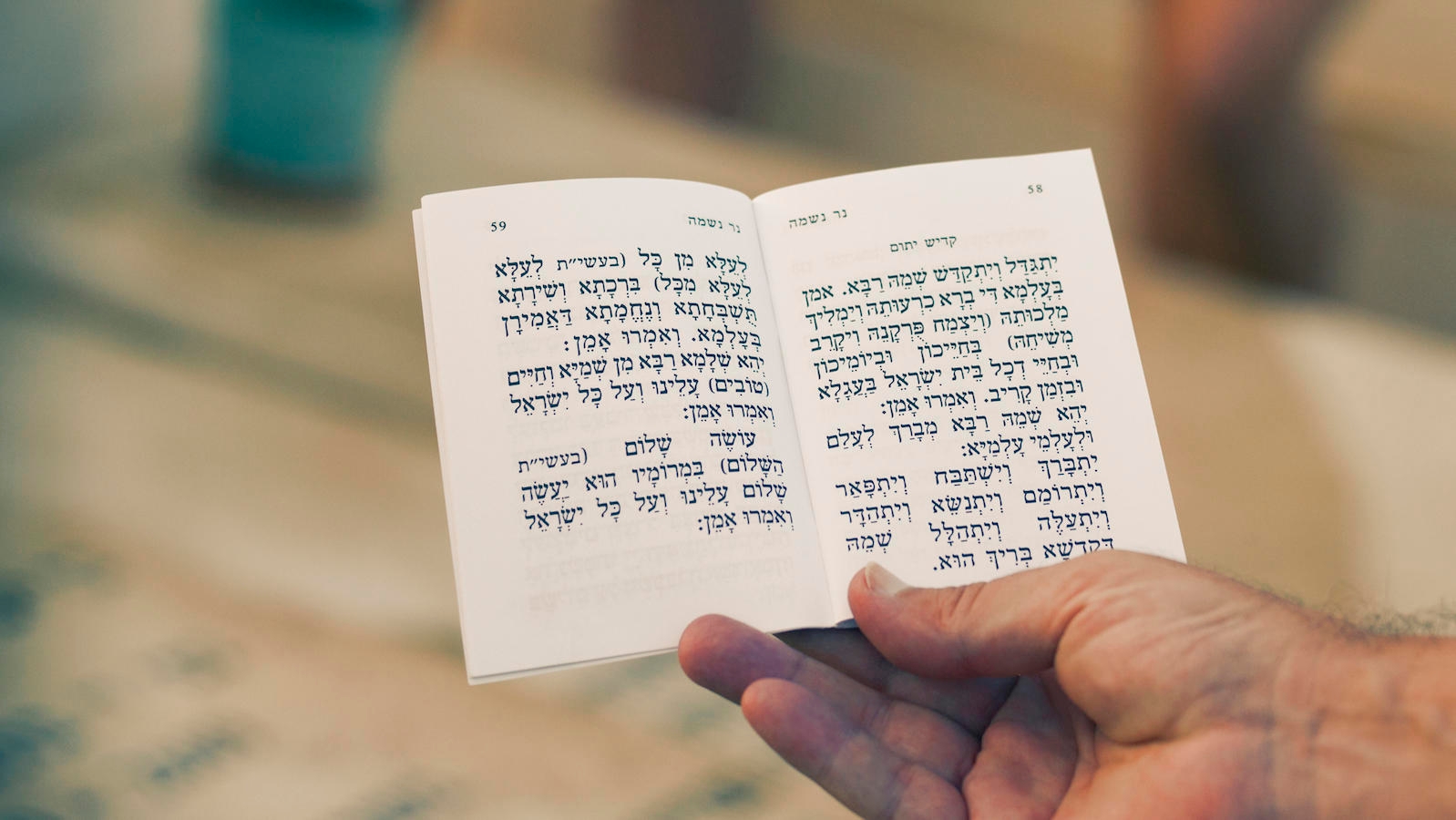

A few weeks ago, my community experienced an unusually high number of funerals within a short period of time. As a result, we endured the challenge and the trauma of providing several shiva minyanim [services with at least 10 Jews where the mourners may recite Kaddish, the memorial prayer] simultaneously. Fortunately, the congregation takes the mitzvah [commandment] of nichum aveilim [comforting mourners] seriously, so I didn’t have to worry about whether or not enough people would attend the ma’ariv [evening] services going on simultaneously in so many homes.

What I did have to ponder was my own embarrassment while forced to lead a prayer service praising God in a place where God’s love and power were so hidden, so missing. After all, each one of these homes sheltered families that had suffered the death of a beloved spouse, parent, or sibling. How could I expect these people to be willing to praise God’s greatness, to extol God’s power, or to express gratitude for God’s goodness. Still aching from the pain of death and separation, these mourners could no longer view God as either benefactor or friend.

Perhaps it was just such a moment of rage and sorrow that originally generated the Yiddish expression, “If God lived on earth, all God’s windows would get broken.”

Yet it was precisely into those homes–homes filled with rage at God’s impotence, homes tormented by an overwhelming abandonment and isolation–that Judaism compelled me to stand and to sing of God’s enduring love and incomparable power.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

In a home that reeled from the loss of a wife and mother, one of its pillars of purpose, meaning, and identity–into that home I had to proclaim the continuing habitability of the universe, the beneficent purpose underlying God’s creation.

And in homes ripped from communal moorings, uncertain of the continuing relevance of friends, community, or Jewish fellowship–into precisely those homes poured friends and congregants, awkwardly reciting the phrases and melodies of our timeless tradition. Did this strange practice make any more sense to them than it did to me?

I, leading the prayers at the front of the minyan, represented the anomaly of God’s love in a place bereft of love, of God’s purpose in a home torn by the random cruelty of finitude and mortality, of God’s covenanted community in a place isolated by loneliness.

Small wonder, then, at my embarrassment and discomfort. Leading the minyan of mourners in what could only feel like a “prayer of the absurd,” forcing mourners to mouth words they would hardly mean, I, and they, needed to confront our puzzlement and frustration at a tradition that imposed this farce on me, this outrage on them. Despite the gap between the mourner’s embittered frustration and the rooted piety of Jewish tradition, I and my congregants were obligated to bring our minyan, our prayers, and our presence to these hurting people. Why?

Why does Judaism mandate seven days of minyanim in the home of a mourning family?

Let’s start with the reality of loss and rage following the death of a lifelong spouse or a beloved sibling. For the person left behind, a jagged hole looms in the center of the heart, an empty space in the depths of the soul. Having built a life around the presence and cheer of one who was deeply cherished, we can only rage against a universe in which such horrors as this death too frequently occur. The Mishnah’s admission that “we cannot understand either the tranquility of the wicked or the suffering of the righteous” provides no comfort, only the recognition of an often bleak and unfair reality. Not without logic, amorphous fury at what has transpired is often directed against God. After all, how can there be a God or how can God claim to be good if this outrage could happen to one so needed, so loved?

It’s difficult enough to endure the death of a loved one, but to simultaneously lose the comfort of God’s love, to exclude the strength and endurance that can emerge from opening one’s heart to God, from sharing one’s pain with the source of all comfort, can only make a painful situation excruciating. As Psalm 42 observes, “Day and night, tears are my nourishment, taunted all day with ‘Where is your God?'” Isn’t that precisely the crisis that every mourner faces? Just when God is most needed, the tragedy that produces such pressing need also renders the divine presence least accessible.

One central function of the shiva minyan, then, is to restore access to God’s love. Words often remain superficial, and sermons regularly fail to penetrate the recesses of the human heart. But the silent presence of fellow Jews, the simple gesture of sitting together or offering an outstretched hand speaks more eloquently than the most lofty speech. God’s presence cannot be articulated or alluded to. But it can be demonstrated. Just by being there, we embody God’s love, and we make that love tangible. “To You, God, silence is praise.”

Think again of the mourner’s devastation in the wake of death. Not only is receptivity to God’s love diminished, but a healthy sense of purpose and a willingness to trust is shattered as well. It is relatively easy to rely on the habitability of the universe while loved ones thrive. It may feel effortless to maintain a buoyant spirit and a cheerful countenance when blessed with health, companionship, and prosperity. But with the death of a loved one, our facade of control dissolves into fantasy. Suddenly, the world we inhabit appears random at best, cruel or deceitful at worst.

Life no longer makes sense. Without conviction, without an affirmation of purpose or meaning, human life becomes impossible. When the psalmist says, “Were it not for the Lord, I would have perished,” he is using biblical language to maintain that we cannot flourish in a random world. Chaos is the enemy of our ability to thrive.

Into a family assaulted by chaos, battered by unjustifiable loss, the shiva minyan asserts continuing purpose, affirms a world view that stands in the face of death and proclaims the imperative of life, acting on the biblical charge for “one generation to laud God’s works to another.” Precisely by reciting prayers that acclaim God’s goodness, we assert our determination to endure, to comfort, and to blossom. The shiva minyan restores a lost vision of how to live, how to retain order and direction in a shattered world.

Finally, a significant component of a mourner’s devastation is the severed sense of belonging. Having lost one of the closest ties to the outside world, one of the most intimate of relationships, the mourner flounders in lonely isolation. Abandonment sets the somber tone of the mourner’s mood.

It’s impossible to be a Jew alone. While sociologists confirm that human identity is formed in community, and object-relations psychology teaches that even an infant’s sense of self derives from its interactions with others, nowhere is that need more pressing than in the isolation of a mourner. And nowhere is the assumption of community more pervasive than in the world of traditional Judaism.

The mourner, then, reels from the universal and human loss of context and belonging–a loss made more acute by the particular way Jews generally can presume the support of their community. The shiva minyan–because it occurs in the home, because it is composed of friends and fellow congregants–does more than remind the mourner of membership in a larger community. It creates that community–precisely where it is most needed. By physically entering the isolation of the mourner, the shiva minyan dispels it.

For all these reasons, the shiva minyan is needed most where is desired least. In a place of anger, the practice of shiva offers acceptance and love. To a heart adrift, the shiva minyan restores direction. And to the agony of individual pain, the shiva minyan creates a portable and persistent community.

The kabbalists [Jewish mystics] spoke well when they pointed out that the only way to gather the shattered sparks of divine light–now held by the forces of chaos and despair–was to enter the sitra ahra, the side of darkness. The only place to provide healing, comfort, and an abiding sense of God’s love and communal support is in the home of the mourner.

“Out of the depths, I called to You, Lord.” And it is out of the depths that healing, community, and solace can hope to emerge.

Reprinted with permission from Wrestling with the Angel: Jewish Insights on Death and Mourning, edited by Jack Riemer (published by Schocken Books).

Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson is the Dean of the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies at the University of Judaism in Los Angeles. He is the author of The Bedside Torah: Wisdom, Dreams, & Visions (McGraw Hill).

Sign up for a Journey Through Grief & Mourning: Whether you have lost a loved one recently or just want to learn the basics of Jewish mourning rituals, this 8-part email series will guide you through everything you need to know and help you feel supported and comforted at a difficult time.

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.

minyan

Pronounced: MIN-yun, meen-YAHN, Origin: Hebrew, quorum of 10 adult Jews (traditionally Jewish men) necessary for reciting many prayers.

shiva

Pronounced: SHI-vuh (short i), Origin: Hebrew, seven days of mourning after a funeral, when the mourner stays at home and observes various rituals.