Raphael Lemkin was a Polish-American lawyer and activist today best known for coining the term “genocide” and leading the charge to have it enshrined in international law as a punishable crime under the 1951 Genocide Convention. Though the convention has not prevented genocides from being perpetrated, Lemkin was singularly responsible for providing the only legal basis on which those who commit them can be punished.

Born 1900, Lemkin was raised on a farm owned by his father and uncle in Bezwodne, Lithuania, then part of the Russian Pale of Settlement. Though he enjoyed playing with his cousins and the children of farm hands, he wrote in his posthumously published autobiography that he would sometimes wander off to contemplate his own thoughts. His intellectual inspiration was his mother Bella, whose own love of languages, painting, literature and philosophy encouraged him to master French, Hebrew, Russian, Spanish and Yiddish.

Sometime during his teenage years, he acquired a copy of Quo Vadis, by the Polish laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846-1916), a fictional account of the Roman Emperor Nero’s almost successful attempt to murder the Christians of his realm. Lemkin asked his mother why the Christians would allow themselves to be killed without contacting the police. She responded: “Do you think the police could help them?” That triggering event led Lemkin, already a voracious reader, to search out other examples of what he would later label genocide — the Huguenots by the French, Catholics by the Japanese, Muslims by the Spanish, Armenians by the Turks and his own people by the Russians.

His concern for the problem of mass murder propelled him to study law, receiving his degree from Lvov University. He later moved to Warsaw, where he worked as an assistant public prosecutor and established a private practice. But he never abandoned his earlier concern with mega tragedies. In 1933, he had hoped to present a paper on what he regarded as the twin crimes of “barbarism” (the destruction of people) and “vandalism” (the destruction of culture) at an international conference in Madrid, but he was prevented from doing so due to the prevalence of antisemitism in Poland at the time.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

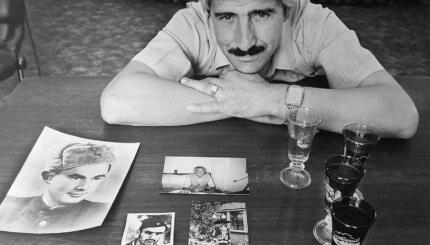

With Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939, Lemkin would initially join the resistance movement. But after a last visit to his family, he fled, arriving in the United States in 1941. Except for his brother Elias and his family, 49 members of Lemken’s family would be murdered in the Holocaust.

In 1944, Lemkin published a massive 674-page volume entitled, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress. The 11th chapter was titled “Genocide” and was only 16 pages, yet along with the convention itself, the chapter remains Lemkin’s enduring contribution to addressing the most horrendous of human tragedies: the collective murder of untold numbers of innocent human beings. Lemkin addressed three issues: the definition of genocide, techniques of genocide, and recommendations for its prevention.

The chapter would come to serve as the foundational text for generations of scholars who would call into being the academic discipline known as Genocide Studies. In it, Lemkin writes:

It [genocide] is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves … Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.

Genocide has two phases: one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor.

Lemkin’s work became one of the legal bases on which Nazi leaders were prosecuted after the war by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Lemkin himself was active at Nuremberg as a consultant to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, the chief American prosecutor. Following the trials, Lemkin returned to the U.S. and resumed teaching law part time, but he would invest the bulk of his energies in working toward the passage of international legislation outlawing what would become known as genocide. Lemkin wrote numerous articles and gave many talks urging U.N. officials to support the Genocide Convention. He himself would haunt the corridors of the United Nations, buttonholing those same officials and writing numerous letters encouraging their support.

On December 9, 1948, the U.N. General Assembly, meeting in Paris, took up debate on the Genocide Convention, formally known as the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Two days later, its 22 member states passed it. The following day, Lemkin was admitted to the hospital suffering from exhaustion — or in his words, “genociditis, exhaustion from working on the Genocide Convention.” He would never regain his full strength and would be further hospitalized on numerous occasions.

On his return to the United States, Lemkin resumed teaching, but he continued to devote the bulk of his energies toward the ratification of the convention, which formally came into force in January 1951. The United States would only ratify the convention in 1988. Israel ratified the convention in 1950.

In 1959, Lemkin died of a heart attack in New York at the age of 59. Only seven people attended his funeral at Riverside Church. He was buried at the Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens.

Tragically, the lessons of the Holocaust and earlier instances of genocide have not been learned by the human community. Numerous instances of genocide continue to afflict our world. That which Lemkin initiated has yet to become the universal standard by which we reject such activities.