Commentary on Parashat Yitro, Exodus 18:1-20:23

- Yitro brings his daughter Zipporah and her two sons, Gershom and Eliezer, to his son-in-law Moses. (Exodus 18:1-12)

- Moses follows Yitro’s advice and appoints judges to help him lead the people. (Exodus 18:13-27)

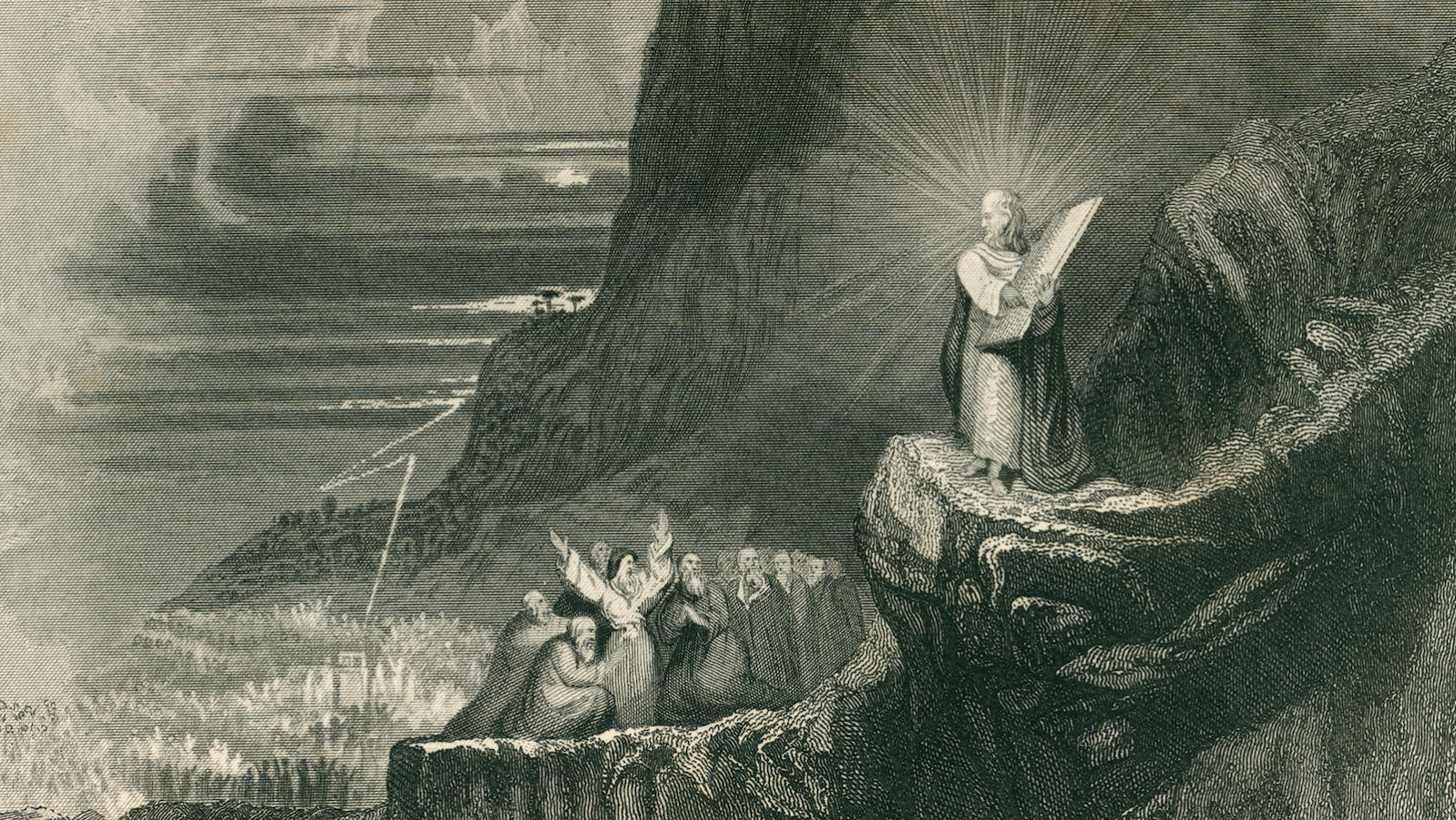

- The Children of Israel camp in front of Mount Sinai. Upon hearing the covenant, the Israelites respond, “All that God has spoken we will do.” (Exodus 19:1-8)

- After three days of preparation, the Israelites encounter God at Mount Sinai. (Exodus 19:9-25)

- God gives the Ten Commandments aloud directly to the people. (Exodus 20:1-14)

- Frightened, the Children of Israel ask Moses to serve as an intermediary between God and them. Moses tells the people not to be afraid. (Exodus 20:15-18)

Focal Point

And Moses went up to God. Adonai called to him from the mountain, saying, “Thus shall you say to the House of Jacob and declare to the Children of Israel: ‘You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to Me. Now then, if you will obey Me faithfully and keep My covenant, you shall be My treasured possession [s’gulah] among all the peoples. Indeed, all the earth is Mine, but you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.’ These are the words that you shall speak to the Children of Israel.” (Exodus 19:3-6)

Your Guide

How do the images and ideas in Exodus 19:3-6 set the stage for what is to come later in Parashat Yitro, namely, the Revelation at Sinai?

What are the implications of the metaphor “I bore you on eagles’ wings”?

What do we learn from these verses about the relationship between Israel and God?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

How would you describe God’s language in this passage? Why did God choose this kind of language at this particular point in Israel’s journey?

Compare Exodus 19:4, “how I bore you on eagles’ wings” with Psalms 91:4, “Beneath His wings you will take refuge.”

There are principles inherent in these verses that are central to the relationship between Israel and God as well as to the Bible’s concepts of covenant and Revelation. What are they?

By the Way…

“You have seen what I did to the Egyptians.” It is not merely a tradition in your hands; it is not in language that I transmit to you, nor through witnesses that I testify to you. But you yourselves have seen what I did to Egypt. How many wrongs they had committed before they fastened onto you! Yet I never punished them until it was you they tormented. (Rashi on Exodus 19:4)

“I bore you on eagles’ wings.” The effect of the image is, of course, to convey intimacy, protection, love, speed; but also, I suggest, the enormous power of the adult eagle, effortlessly carrying its young through the air. In other words, it engenders in the people a sense of their own lightness. It deflates their grandiosity and evokes a relation to God, in which their kavod, their weightiness, becomes insignificant. (Aviva Gottlieb Zornberg, The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus, Doubleday, 2001, p. 258)

“I bore you on eagles’ wings” so that now you no longer have any human master above you. Hence you are now in a position to accept the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Heaven, and I expect you to hearken to My voice. (Shem MiShmuel/Rabbi Abraham Bornstein, cited by Alexander Zusia Friedman in Wellsprings of Torah, Judaica Press, 1980)

Our path in the history of faith is not a path from one kind of deity to another but in fact a path from the “God who hides Himself” (Isaiah 45:15) to the One who reveals Himself. (Martin Buber, On the Bible: Eighteen Studies, Schocken Books, 1962, pp. 64-65)

Today God revealed Himself to me/like this:/Someone put His hands over my eyes/ from behind:/Guess who? (“Revelation” by Yehuda Amichai in Now in the Storm, Poems, 1963-1968)

The revealed is welcomed in the form of obedience. Rather than being seen in terms of received knowledge, should not the Revelation be thought of as…awakening? (Emmanuel Levinas, Beyond the Verse, Indiana University, 1994, pp. 146 and 150)

“Now, then, if you will obey Me faithfully….” If you will now take it [the covenant] upon yourselves, it will be sweet for you from now on, for all beginnings are difficult. (Rashi on Exodus 19:5)

The people of Israel will be a treasured possession of God only if they listen and fulfill their covenant. Their status is not based on some intrinsic quality but on their behavior. God is about to make a covenant with them. If they keep their part of it, then they will be s’gulah [a treasured possession]. (Richard E. Friedman on Exodus 19:5 in Commentary on the Torah, Harper San Francisco, 2001)

S’gulah denotes an “exclusive” possession to which no else except its owner is entitled and which has no relationship to anyone except its owner.” (Samson Raphael Hirsch on Exodus 19:5 in The Pentateuch, Judaica Press, 1997)

Your Guide

How do you react to Yehuda Amichai’s characterization of God as one who plays “Guess who?” with humanity?

What thorny theological issues face the modern Bible reader in Exodus 19:3-6? Do any of the commentators give you hope or comfort?

D’var Torah

I remember the following story told by Rabbi Joseph Levine:

He was a seventeen-year old boy. The radiation had taken his hair, the surgeons had taken his right arm, the cancer was taking his life. He drifted in and out of a coma. His father and mother sat by his bedside day after day. Suddenly his eyes opened, he saw his dad, and said, “I’m scared. Sometimes I don’t know who I am.” His father asked, “Do you know who I am?” “Why, yes, you’re Dad.” “OK, then,” his father replied, “don’t worry because I know who you are.” (CCAR Yearbook, 1980)

“I know who you are:” a parent speaking to the soul of his child. With the word s’gulah (Exodus 19:5), God speaks directly to the soul of the Israelite and reassures the person adrift, an ex-slave, a person ignored, devalued, and bereft of identity. “I know who you are,” says God. “You are am s’gulah, My treasure.”

Always aware of the six million times that the promise cited in Psalms 91 was broken, we are impatient with God-concepts. Our questions are real and urgent: What is God’s role in history? What is God’s role in our lives? Tired of the feeling that we are carrying God on our wings–doing all the work, wrestling a shadow, scratching around for traces of God’s presence–we hope that, maybe once or twice in our lives, God will come from behind and say “Guess who?” like in Amichai’s poem.

We awaken to God’s Revelation, states philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, through the modality of obedience: “Now then, if you will obey Me faithfully…” (Exodus 19:5). At first, the word “now” hardly seems necessary in this text. But, as Rashi points out, “now” is at the heart of the matter. “Beginnings are difficult,” he says, quoting the midrash: difficult because of what has come before–the slavery, the feelings of abandonment and alienation, the broken promises.

But now (and it is always now) a vast opportunity is offered: Obey and through obedience receive God’s love and God’s gift of an identity. “I know who you are,” says God. “You are a kingdom of priests.” As Rabbi Levine states about the father in his story, “That’s pastoral care!”

Provided by the UJA-Federation of New York, which cares for those in need, strengthens Jewish peoplehood, and fosters Jewish renaissance.

Yehuda

Pronounced: yuh-HOO-dah or yuh-hoo-DAH (oo as in boot), Origin: Hebrew, Judah, one of Joseph's brothers in the Torah.

Adonai

Pronounced: ah-doe-NYE, Origin: Hebrew, a name for God.