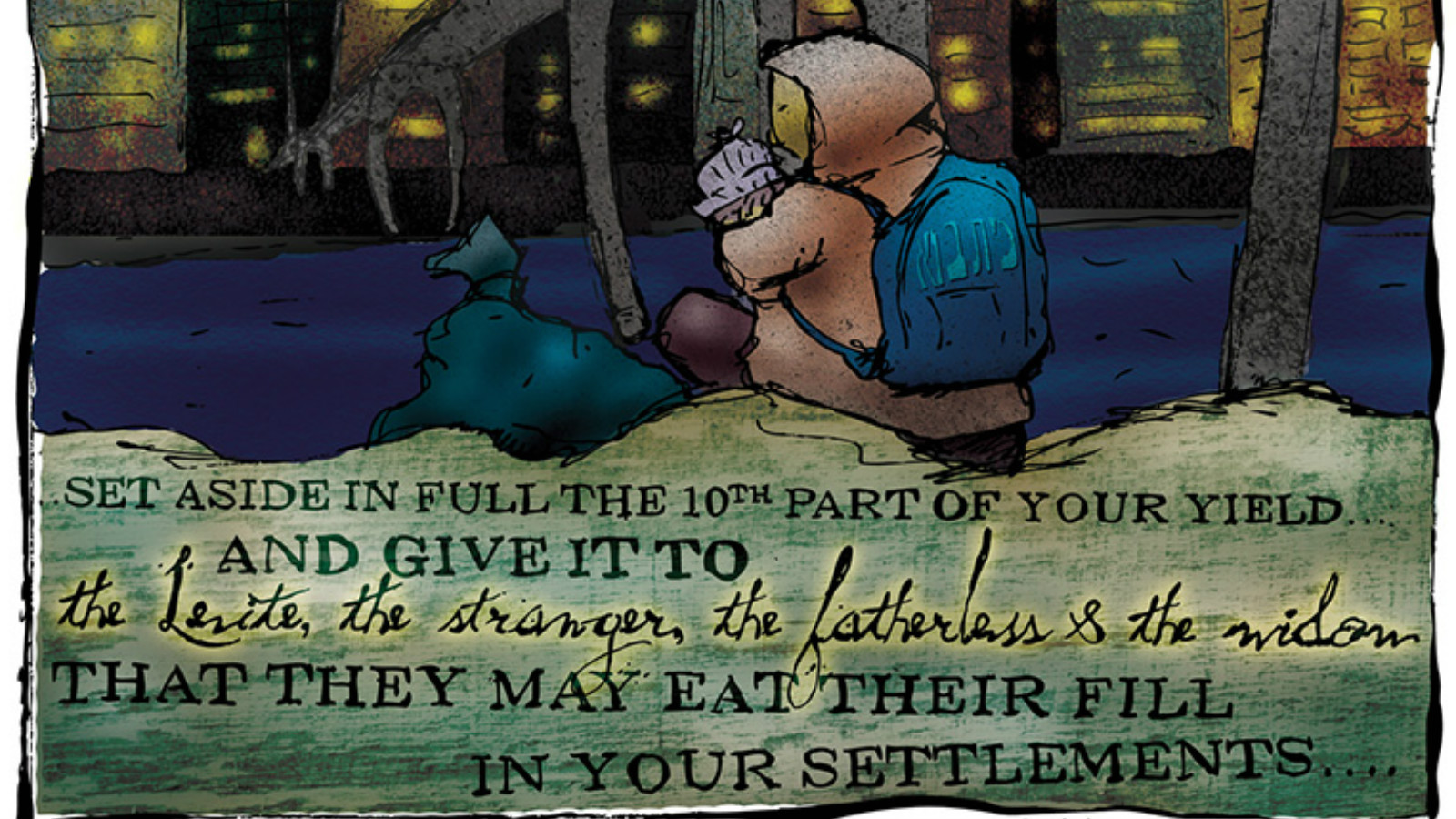

Commentary on Parashat Ki Tavo, Deuteronomy 26:1-29:8

Relaying instructions for a time in the not so distant future when the Israelites would be living in the land of Israel and enjoying its bounty, Moses instructs them to fill baskets with the first fruits of their crops and to present them at the altar while reciting:

“My father was a fugitive Aramean. He went down to Egypt with meager numbers and sojourned there; but there he became a great and very populous nation. The Egyptians dealt harshly with us and oppressed us; they imposed heavy labor upon us. We cried to Adonai, the God of our ancestors, and Adonai heard our plea and saw our plight, our misery, and our oppression. Adonai freed us from Egypt by a mighty hand, by an outstretched arm and awesome power, and by signs and portents, bringing us to this place and giving us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. Wherefore I now bring the first fruits of the soil which You, Adonai, have given me” (Deuteronomy 26:5–10).

These verses, from Parashat Ki Tavo, provide a brief synopsis of the Exodus and followed by an account of the Israelites’ arrival at the promised land. This ritual, part commemoration and part expression of gratitude to God, becomes affiliated with the holiday of Shavuot, which marks the late spring harvest. The third chapter of Mishnah Bikkurim builds upon what the Torah reports and describes the pageantry of the celebration during Temple times, as remembered by the rabbis who stood in the wake of its destruction. These verses from this week’s parashah may sound familiar as they are central to another ritual as well: the telling of the story of the Exodus during the Passover seder.

It makes sense that the verses that describe the bringing of first fruits to the Temple form the basis of the liturgy for the first fruits ritual. Even more so if you pause to imagine what it must have felt like to haul produce up the Jerusalem hills to the Temple under the heat of the Judean sun. The weary farmers must have been thrilled that a relatively short paragraph was selected for these purposes, allowing them to seek hydration and shade soon after arriving at the front of the line. But on Passover, when the Haggadah is recited in the comfort of one’s home and over the course of an entire evening, there is both time and opportunity for a longer version of the story. Wouldn’t it make more sense to read the chapters of the Book of Exodus that describe the escape from Egypt instead of a short summary that, in its original context, has more to do with settling the land and bringing first fruits than it does with leaving Egypt?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

A hint at why this curious choice may have been made can be found in Mishnah Bikkurim 3:7, although it will take a short explanation to get there. The mishnah teaches:

“Originally all who knew how to recite the verses would recite them. And for those who did not know how to recite, others would read it for them (and they would repeat the words afterwards). When they refrained from bringing, it was decreed that others should read the words to both those who could and those who could not recite.”

Those who knew how to read or recite the verses by heart would do so. But those who could not recite on their own were embarrassed and stopped coming. In response, a change was made and everyone who brought first fruits was prompted, whether they needed the help or not, so that it would not be apparent who needed it. This change had the upside of being more inclusive. It likely also made the entire procedure take much longer.

Now let’s envision what it must have been like to be standing on the Temple Mount, waiting in line and listening to the nearly endless call and response of Deuteronomy 26:5–10. Each and every person in line would have heard the verses recited aloud many times over and, by day’s end, committed all of it to heart. Now imagine this procedure repeated year after year after year.

Based upon the report of the mishnah, it seems probable that these verses became among the most well-known in the Torah — certainly among those that recounted the Exodus. What better verses for the rabbis to place at the center of the Passover ritual than ones everyone already knew by heart?

As you read this week’s parashah, listen not only for the echo of Moses’s words preparing the people to enter the land of Israel, and not only for the voices of our ancestors as they delivered their first fruits as a present to God in gratitude for the bounty which they had been given, but also for those of the earliest of rabbis, as they selected the same words to be a part of our Passover celebration.