On a hot and humid Cincinnati evening in July 1883, over 200 distinguished guests, Jews and non-Jews alike, gathered at the exclusive Highland House restaurant to celebrate a milestone in the history of American Judaism: Hebrew Union College, which Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise founded, had just ordained its initial graduating class. America had finally produced four homegrown, ordained rabbis. Most of the diners had just attended the eighth annual meeting of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC), the first association of American Jewish synagogues, which Rabbi Wise had also organized. The graduates and guests looked forward to an evening of gastronomical pleasures. What they witnessed was the beginning of the end of Wise’s dream of American Jewish religious unity.

READ: What Really Happened at the Original Trefa Banquet

For the nearly four decades after his arrival in America from his native Bohemia, Isaac Mayer Wise envisioned creating and sustaining a unified American Judaism that balanced European tradition and New World realities. He built the Hebrew Union College to train American rabbis and created the Union of American Hebrew Congregations as a forum for traditional and reform-minded rabbis and congregations to air and resolve their differences.

By 1883, the fact that some traditionalists had introduced a degree of modernization such as English sermons and English prayers into their services and the more liberal ones even allowed organ music and mixed choirs of men and women encouraged Wise to hope for convergence. He was aided by his close friend, Reverend Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia, a leading traditionalist figure who, like Wise, focused more on uniting American Jewry than on doctrinal differences.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Other rabbinical voices were not so united in vision and purpose. Especially contentious were the so-called Eastern radical reformers, led by Rabbi David Einhorn of Baltimore. Veterans of the radical reform German rabbinical conferences of the 1850s, the liberals intended to expunge what they deemed outmoded religious practices such as kashrut–derisively called “kitchen Judaism”–and the second day of holiday observances. Some radicals even advocated observing Shabbat on Sunday.

Wise himself damaged the reform-traditionalist détente in 1855 by introducing, at a meeting intended to demonstrate the harmony of American Judaism, his prayer book, Minhag America. Though moderate in its reforms, the book distressed the traditionalists, including Leeser, and did not go far enough for some of the radical reformers.

Wise’s diplomatic genius contained these differences. By creating the UAHC in 1873 and convincing the organization to found Hebrew Union College in 1875, Wise shakily maintained the fragile traditionalist-reformer détente into the beginning of the 1880s. Historian Abraham J. Karp notes that Wise “understood that congregations could be united through participation in a project rather than through agreement on resolutions” and proposed creating the seminary as a concrete way to develop an American rabbinate and, thus, an American Judaism.

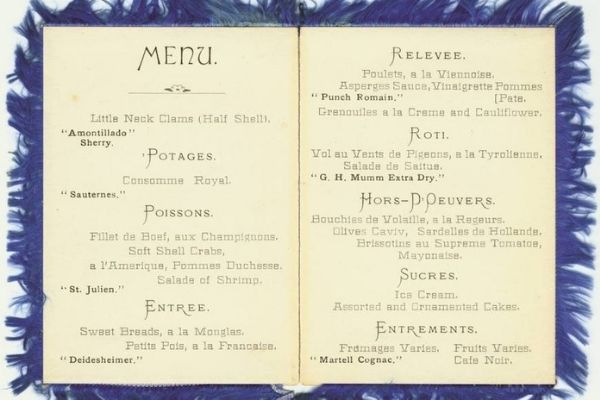

The celebratory banquet for the first Hebrew Union College graduating class on that fateful July evening tangibly confirmed for Wise the efficacy of his strategy. However, the first course on the menu was “Little Neck Clams (half shell).” According to the memoirs of Rabbi David Phillipson, the course provoked “terrific excitement” and “two rabbis rose from their seats and rushed from the room.” While leaders gave unity speeches from the podium, a number of traditional rabbis sat stoically through the meal, failing to applaud, and refusing to taste even one morsel of the “Soft-shell Crabs” and “Salade of Shrimps,” or the ice cream and cheese that followed the meat courses.

Historians debate whether Wise approved the menu, the Jewish caterer acted on his own, or the Einhorn faction surreptitiously ordered the treyf courses to force a showdown. Wise claimed no knowledge of how the shellfish got on the menu. He personally kept a kosher home and claims to have ordered Gus Lindeman, the caterer, to serve only kosher food. Lindeman did serve kosher meat but “supplemented” it with the shellfish and dairy desserts. A later investigation by a panel of UAHC rabbis cleared Wise of wrongdoing, but the damage was already done.

The events of that evening, dubbed in history the “trefa banquet,” forged an important link in the chain of events leading to the formal break between tradition and reform. In the three years after the banquet, a series of debates between radical Rabbi Kaufmann Kohler and traditionalist Alexander Kohut crystallized the positions of each side. In 1885, the UAHC conference in Pittsburgh, dominated by radicals, adopted a platform of Reform Jewish theology that defined the movement for over half a century. In 1886, some change-oriented rabbis who could not go as far as the Pittsburgh radicals established the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, laying the foundation for Conservative Judaism. In 1888, America’s Orthodox community decided to recruit a chief rabbi from Eastern Europe to serve as a regnant authority. Later that year, Rabbi Jacob Joseph of Vilna arrived in New York City to become the first official chief Orthodox rabbi in America.

After these events, there was no turning back. American Judaism divided into organized movements, each claiming its right to define Jewish religious practices. The “trefa banquet” did not cause that division, but most colorfully symbolized the sensibilities and principles that led to it.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.

kosher

Pronounced: KOH-sher, Origin: Hebrew, adhering to kashrut, the traditional Jewish dietary laws.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

treyf

Pronounced: TRAYF, Origin: Yiddish, not kosher

kashrut

Pronounced: kahsh-ROOT, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish dietary laws.