The signing ceremony in Washington was designated for September 13, 1993. Like the long, feckless negotiations in the State Department, the event nominally took place under the joint American Russian aegis of the original Madrid conference [The Madrid Peace Conference took place in 1991. This conference, hosted by the government of Spain, and co-sponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union, brought together Israel and her Arab neighbors, including Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and the Palestinians, for a series of preliminary peace talks]. Gathered in the White House Rose Garden, therefore, the participants included not only PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, PLO negotiator Abu Ala’a (Ahmed Qurei), Israeli Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, U.S. President Bill Clinton, and U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher, but also Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev. Indeed, once Peres and Abu Ala’a performed the act of signature, both Christopher and Kozyrev added their own signatures as “witnesses.”

The twenty three page “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self Government” consisted of a basic text, four annexes and agreed minutes, and the September 9 10 exchange of letters between Arafat and Rabin. Less than a comprehensive treaty, the document in effect was an agreement to reach agreement, leaving the details to be negotiated between the parties. Nevertheless, under the declaration’s collective guidelines, Israel would begin its military withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho as early as December 1993, and by April 1994 leave to a Palestinian authority virtually full self government in these enclaves.

Subsequently, a five year transitional period would commence for the West Bank in its entirety, and early on during that time span the Israeli civil administration would transfer “empowerment” to the Palestinian authority in five carefully delimited spheres: education, health, social welfare, taxation, and tourism. It was understood, too, that the spectrum of self government would rapidly expand into other areas, including the judiciary and water control. The Israeli army similarly would deploy outside the main West Bank population centers, although retaining authority for internal security in the region. From beginning to end, of course, Israel would retain full legal jurisdiction over Jewish settlements in the territories. Two years into interim empowerment for the West Bank, negotiations would commence between Israel, the Palestinians, and Jordan on the final status and borders of the territories, as well as of Jerusalem. The process would be completed in three years. Indeed, the entire five year timetable was based on the original Camp David accord of fifteen years before.

Yet the Declaration of Principles diverged from that earlier, 1978 document in several important respects. For one thing, it resolved the question of whether, as the Palestinians claimed, their interim empowerment would be territorial, covering the entire West Bank and Gaza areas; or whether, as Begin and Shamir had insisted, it should be exclusively personal, covering only the inhabitants of Palestine, but not the territories in which they lived. Here Rabin and Peres had affirmed that Palestinian empowerment would indeed be territorial. Except for the network of Jewish settlements and Israeli military installations, empowerment (initially in the five spheres cited above) would cover the totality of the land on which Arabs traditionally had lived, built their homes, worked, and raised their crops and families.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Of equal significance, the five-year interim period would begin immediately upon elections for a Palestinian Council and the council’s formal inauguration. Camp David also had provided: “When the self government authority [administrative council] in the West Bank and Gaza is established and inaugurated, the transitional period of five years will begin.” Yet the Camp David format specified that the permanent status negotiations must be conducted between “Egypt, Israel, Jordan and the elected representatives of the inhabitants of the West Bank and Gaza.” In practice, then, no agreement ever was reached on the realm of the self governing authority; hence the authority was never “established and inaugurated” -and thus, fifteen years after Camp David, the five year transitional period had not yet begun. This time, the uncertainties of Arab intramural politics would not become a pretext for delay (“I do not believe that democracy can be imposed artificially on another society,” Peres commented dryly later). The Declaration of Principles announced an intention to move ahead to Palestinian empowerment forthrightly, vigorously, and extensively -and, in the case at least of Gaza and Jericho, immediately.

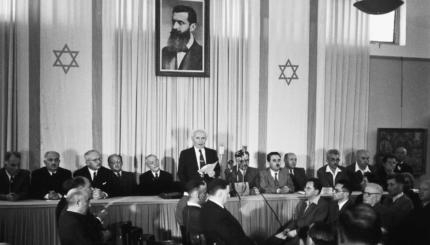

So it was, on September 13, 1993, in the bright sunshine of a Washington morning, before an audience that included former United States presidents Jimmy Carter and George Bush, former secretaries of state Henry Kissinger, Cyrus Vance, and James Baker, that Rabin solemnly declaimed:

Let me say to you, the Palestinians, we are destined to live together on the same soil in the same land. We, the soldiers who have returned from battles stained with blood; we who have seen our relatives and friends killed before our eyes; we who have attended their funerals and cannot look into the eyes of their parents; we who have come from a land where parents bury their children; we who have fought against you, the Palestinians, we, say to you today in a loud and clear voice, enough of blood and tears. Enough!

Arafat responded in the same spirit, promising “to implement all aspects of UN Resolutions 242 and 338,” and assuring Israel that “the right to [Palestinian] self-determination” would not “violate the rights of their neighbors or infringe on their security.” In the flurry of handshakes afterward, the PLO chairman walked over to Rabin, who until that moment had avoided speaking to him or even standing next to him, and offered the Israeli prime minister his hand. After a moment’s hesitation, and with a tight smile that onlookers might easily have confused with a grimace, Rabin accepted the hand and gave it two perfunctory shakes. Although no words were exchanged, the media treated the event as one of modern history’s decisive watersheds

Reprinted from A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Times published by Alfred A. Knopf.