The prophecies of Hosea and Amos are part of a collection of books known as the trei asar (The Twelve) or the Minor Prophets. Both prophets were active during the eighth century B.C.E. during the reigns of Jeroboam II of Israel and Uzziah of Judah. Hosea apparently continued beyond this period through the reigns of Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah of Judah.

Read Hosea and Amos in Hebrew and English on Sefaria.

Despite the essentially “religious” nature of prophecy, an understanding of the prevailing political and economic circumstances is a vital element in deciphering the prophets’ message. The first half of the eighth century B.C.E. brought a period of relative stability and prosperity to the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, for some segments of society at least. The relative weakness of Syria meant that Israel was no longer harried, nor subject to the payment of tribute, and Jeroboam extended the nation’s borders. Likewise in Judah, Uzziah enjoyed a long reign of relative peace and prosperity.

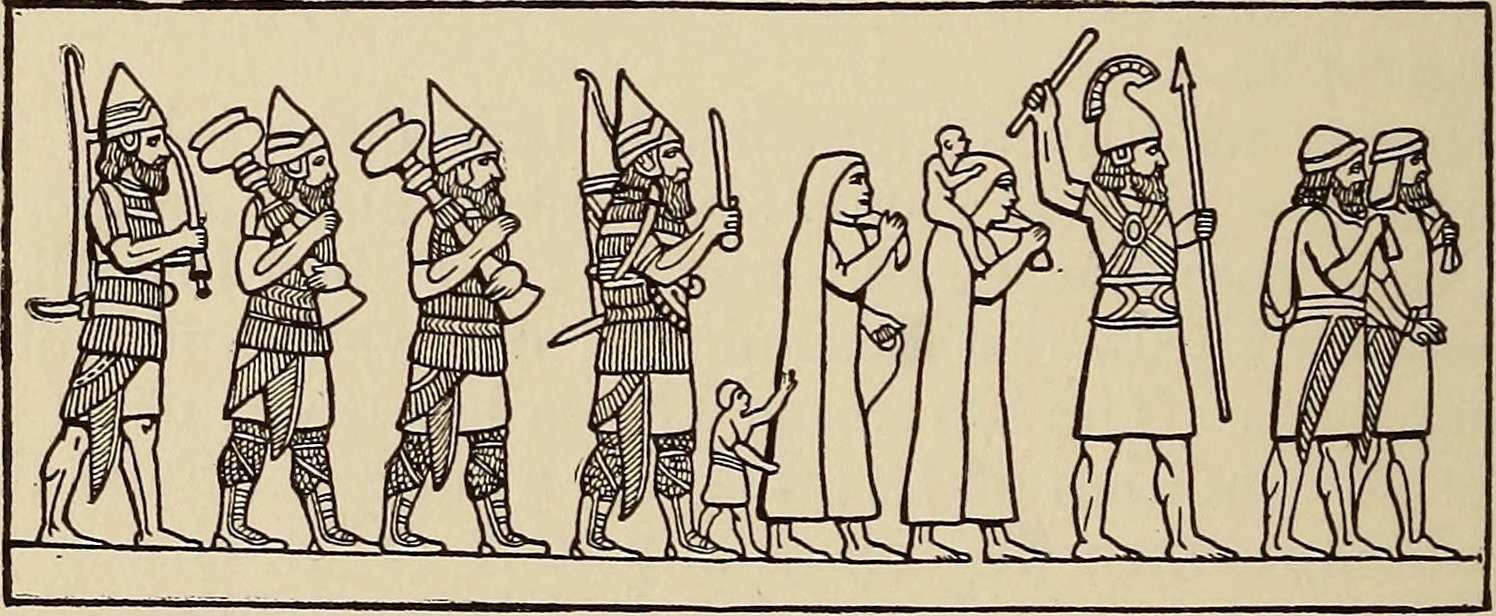

The end of the Jehu dynasty in the North came with the assassination of Jeroboam’s son Zechariah after a merely a year on the throne. Subsequently the kingdom descended into chaos. Between the death of Jeroboam and the fall of Samaria (the capital city) in 722, Israel had six kings, all but one of whom was assassinated. Beginning in 743 B.C.E., the westward sweep of the Assyrian Tiglath-Pileser III contributed significantly to this chaos. The shifting patterns of foreign alliances, revolt against vassal status and return to payment of tribute are reflected in the book of Hosea.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Amos: “Neither a Prophet nor the Son of a Prophet”

Amos is introduced as a noked ( a shepherd or breeder of sheep) from Tekoa, a village in Judah. Elsewhere he is described as a cattleherder and a tender of sycamore trees. There has been much speculation as to the meaning of Amos’ statement that he is neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet. (One possibility is that he was making it clear that he was not part of the circle of “professional” prophets, many of whom were attached to the courts of kings.)

Judgment for Social Injustice

The first five oracles in Amos are pronounced against neighboring peoples. All are indicted for war crimes. The sixth oracle accuses Judah of disregarding the Torah and God’s laws, while the seventh sets out Amos’ prophetic agenda: Israel will be punished for its treatment of the poor and righteous, for offenses against the code of sexual ethics, for keeping a pledge overnight, and inappropriate behavior at a shrine. The essential qualities for Amos are mishpat (correct judgment) and tzedakah (righteousness).

It is upon those who pervert justice and throw aside righteousness that disaster will fall. Addressing the northern kingdom (referring to it as “Yosef” or Joseph ), Amos describes a society in which the righteous are hated, bribes are taken and the poor are turned away. People are traded for the price of a pair of sandals while others lie on couches, eating choice meats making music and drinking wine. Feeling themselves to be secure they have no concern for the plight of Yosef, the nation as a whole. They will be the first to be taken away.

Can doom be averted? Amos calls on the people to “Seek God and live” (3:5), and this is later echoed in the exhortation “Seek good and not evil that you may live” (5:14). Nevertheless, early in this section Amos describes an adversary who will surround and despoil the land leaving nothing but a small remnant. He quotes a list of chastisements–famine, drought, locusts, blight and violent death–none of which have brought Yosef back to God. At the end of the section, judgment is declared on both great and small.

The Day of the Lord

As part of his social critique, Amos radically reinterprets the concepts of Israel’s election and the “Day of the Lord”. God’s special relationship with his people will bring punishment, not divine favor (3:2). The Day of the Lord, eagerly anticipated by the people as a time of rejoicing, will on the contrary be a day to be feared. It will bring darkness, not light; death not refuge. In addition, the prophet rejects the cult as practiced “I hate, I despise your feasts ?. I will not smell the sacrifices of your solemn assemblies, But let justice rain down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” (5:21, 24)

Chapters 7-9:6 include five visions. After each of the first two visions of destruction, God relents from his judgment following special pleading from Amos. But after the third vision there is no pardon. The confrontation with the prophet Amaziah interrupts the sequence. Amos prophesies the end of the Jehu dynasty, the destruction of the sanctuaries and the demise of Amaziah himself. The fourth vision turns on a word play: Amos sees a basket of summer (kayitz) fruit and God declares the end (keitz) of His people. In the final vision, the Lord stands beside an altar and commands destruction and death.

The final section of the book has been the subject of some debate. The first oracle is again one of destruction, but beginning with verse 9:11, Amos prophesies the restoration of “the Tabernacle of David” and the return of Israel from captivity. (Some see this as a later addition to the text.)

Hosea’s Marriage Metaphor

We know even less about Hosea ben Beeri than we do about Amos. He apparently operated in the Northern kingdom, and his target was predominantly, but not exclusively, Ephraim. The book can be divided into three parts: Chapters 1-3 deal with Hosea’s “marriage”; 4-13 comprise a series of oracles for the most part prophesying doom; and finally in chapter 14, there is the promise of restoration.

The book opens with what might be considered “performance” prophecy. Hosea is commanded to act out through his marriage the coming judgment on Israel. His marriage will dramatize the breakdown in the relationship between God and His people Israel. Hosea’s wife will be a harlot, and her children’s names will represent God’s estrangement from Israel. Nevertheless, the scene closes with God exercising compassion. The second scene passionately, even violently, portrays God’s rejection of the wayward Israel the harlot. But the chapter closes in the wilderness with beautiful words of betrothal.

In the closing scene of this section, the prophet is told to love an adulteress, just as God loves Israel. Once acquired, she is to be placed in solitary confinement without a husband, so mirroring the desolate Israel, alone with no leader or cult. Yet desolation will be followed by restoration.

Israel as Unfaithful Wife; Idolatry as Harlotry

This language and themes of the opening chapters thread their way through the remainder of the book. In the early chapters, the keywords are “harlot” and “harlotry”–Israel chases after false lovers rather than remaining faithful to her God. The love which God has for Israel is contrasted with Israel’s futile actions. Clearly a major factor in God’s complaint against his people is their continuing belief in the efficacy of their sacrifices to the ba’alim (Canaanite gods) : “Ephraim is joined to idols” (4:17). They sacrifice on hilltops and under trees (certainly proscribed in Deuteronomy). They are so deeply imbued with the spirit of harlotry that they will be unable to find God even when they seek Him.

The idea of repentance and return does occur throughout the book, but largely in the context of Israel’s unwillingness or inability to do so. Nevertheless, the oracles of doom are interspersed with messages of hope: “Come let us return unto God … (6:1 )…he will surely come and bind up our wounds?” Later God declares, “I will not execute the fierceness of my anger? (11:9).

Concern with the cult is not the whole story for Hosea. Ethical failings are not ignored: “swearing and lying. and killing and committing adultery ? blood leads to blood” (4:2). Echoing Amos he declares, “For I desire mercy, and not sacrifice?”(6:6). Political considerations are also evident. As Ephraim chases after foreign alliances, he is characterized as “a silly dove, without understanding. They call unto Egypt, they go to Assyria?.” (7:11).

Wilderness and Agriculture; Violence and Tenderness

The wilderness wanderings are an important element in the book of Hosea. The wilderness provides an instrument of punishment, but it also represents the first encounter between God and His people and the place where their relationship will be renewed:

Behold, I will bring her into the wilderness

And speak tenderly unto her

And she shall respond there, as in the days of her youth. (Ezekiel 2:16-17)

Also striking is the pervasiveness of agricultural imagery and the passionate, sometimes violent, tenor of the language. Israel is a “luxuriant vine” (10:1), the people “sow the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind” (8:7). Ephraim has no future, its roots shriveled, it bears no fruit. The encroachment of thorns and thistles is indicative of the road to destruction and exile. God their savior will become as a lion or an enraged she-bear and will “devour them like a lioness” (13:8). As Samaria falls, “their infants shall be dashed in pieces, and their women with child ripped open” (14:1). The final chapter returns to the fields and images of fertility as God tenderly revives and restores his people.

Comparing the Two Prophets to the North

Amos and Hosea have often been contrasted, the former characterized as a critic of cultic waywardness and the latter as a champion of social justice. In reality, the contrast is not so simple. Both were responding to the changing conditions as an apparently secure but decadent society was overtaken by rapid political and religious disintegration.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.