Traditionally, on Shabbat and holiday mornings, a selection from one of the biblical books of the Prophets is read after the Torah reading. The portion is known as the haftarah (hahf-tah-RAH, or in Ashkenazic Hebrew: hahf-TOH-rah). On two fast days, Yom Kippur and Tisha B’av, a haftarah is recited at both morning and afternoon services.

While the Torah reading cycle proceeds from Genesis through Deuteronomy, covering the entire Five Books of Moses, only selected passages from the Prophets make it into the haftarah cycle. A cluster or three or four berakhot (blessings), depending on the occasion, follows the haftarah. Their call for prophecy to be fulfilled and for God to restore the Jewish people to Zion serve as a finale to the full set of the day’s scriptural readings, Torah and Haftarah together.

Prophets of Truth and Justice

Rabbinic literature does not discuss the origin of the practice of reading publicly from the Prophets in a formal cycle. We might look to the liturgical setting of the haftarah, then, for some clue about its intended function. In addition to berakhot (blessings) recited after the portion, every haftarah is introduced with a berakhah (blessing) praising God for having “chosen good prophets and accepted their words, spoken in truth.”

The formula goes on to note that God shows favor to “the Torah, Moses His servant, Israel His people, and the prophets of truth and justice.” This focus on the reliability of the Israelite prophets has led some scholars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Adolf Büchler and Abraham Zevi Idelsohn, to speculate that the institution of the haftarah originated in bitter polemics among competing religious groups in Ancient Israel — the Jews and the Samaritans.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Samaritans

The Samaritans were then an ethnic group rivaling the Jews in numbers, power, and influence. The Samaritans insisted on the exclusive truth of the Torah (their version differs somewhat from the Jewish Torah) and rejected all prophets after Moses. That rejection could well have formed the background for the practice of reading from the Prophets in synagogues. By declaring the prophetic books authoritative and their origin divinely inspired, the Jews may have sought to exclude Samaritans from local communities and offer a statement of opposition to a major tenet of Samaritan theology. This view is now accepted widely, but not universally, among scholars of Jewish liturgy.

Whatever the origin of the haftarah, it became, as Professor Michael Fishbane notes in the introduction to his Haftarot commentary volume (Jewish Publication Society, 2002), one of the three components of the public recitation of scripture in the ancient synagogue. This public reading reflected three sources of authority: the Torah, which is the ultimate source of law; the haftarah, which presents the words of the Prophets, who provided moral instruction and uplift; and the sermon or homily, which drew on the authority of the Rabbis to interpret and legislate.

How Were Haftarah Passages Selected?

It may be that haftarah passages were originally selected arbitrarily, by randomly opening a scroll of one of the prophetic books and reading whatever one happened to find, or at least the choice was not predetermined by tradition. So it would appear from a story in the Gospel of Luke (4:16ff.), in which Jesus, visiting a synagogue in Nazareth on a Shabbat, is handed a scroll of Isaiah and asked to open it and read from it. Jesus is reading a haftarah, it seems, and some scholars interpret the verses to mean that the place at which the reader was to begin and end was not indicated to him. (Büchler disagrees, and Ismar Elbogen, in his authoritative history of Jewish liturgy, despairs of ever answering the question definitively.)

Later, traditions developed of reading a particular passage with each weekly Torah portion. The Babylonian Talmud (Megillah 29b) suggests that a haftarah should “resemble” the Torah reading of the day. The haftarah is, in fact, usually linked to a theme or genre from the Torah reading. For example, on the week when the Torah reading features the song sung by the Israelites when they witnessed the parting of the sea at the Exodus (Exodus 15), the haftarah includes the Song of Deborah sung in response to the military victory of the chieftain Deborah and her commanding general, Barak (Judges 5). When the Torah reading relates the story of the 12 scouts sent by Moses to spy out Canaan, the haftarah (from Joshua 2) focuses on the two spies sent by Joshua to Jericho in advance of his campaign to conquer that city.

The haftarah for a given holiday is either linked closely to a core theme of the holiday’s observance or captures something of its later echoes in the Bible. Thus, the theme of God’s readiness to forgive sin underlies the choice of Jonah for the afternoon of Yom Kippur, and the observance of Sukkot in the idyllic future, as related by Zechariah, serves as the haftarah for the first day of that holiday.

Spotting the connection, sometimes very subtle, between the Torah reading and haftarah is part of appreciating the artistry of Jewish liturgy. Identifying that correlation can be a source of intellectual and aesthetic enjoyment for synagogue-goers, and is the subject of considerable commentary.

Many weeks, though, the Shabbat morning haftarah bears no relationship to that day’s Torah reading, but is instead a haftarah (or one of a series of haftarot) geared to nearby events on the Jewish calendar. On the Shabbat before Purim, for example, when the Torah reading ends with an extra passage on the destruction of Amalek, the haftarah (from 1 Samuel) recounts the tale of the Amalekite king spared by Samuel. The first word of that haftarah, “Zakhor” (“Remember”) lends its name to the day: Shabbat Zakhor.

Such is the practice on other occasions as well. The haftarah on the Shabbat between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (the first word of which, “Shuvah,” lends its name to Shabbat Shuvah) issues a call for repentance appropriate to the 10-day period in which it falls. The haftarot of the three Shabbatot that precede Tisha b’Av sound a warning of impending disaster appropriate to the upcoming observance of the anniversary of the Temple’s destruction. For fully seven Shabbatot afterward, the haftarot offer consolation and encouragement, as if the destruction were a current event.

Not all Jewish communities share the same selections of haftarah for each Shabbat or holiday. The customs of major Jewish ethnic groups vary from each other, and even within a given group — Ashkenazi, Sephardic, Yemenite, etc. — there are local variations.

Different Literature, Different Music

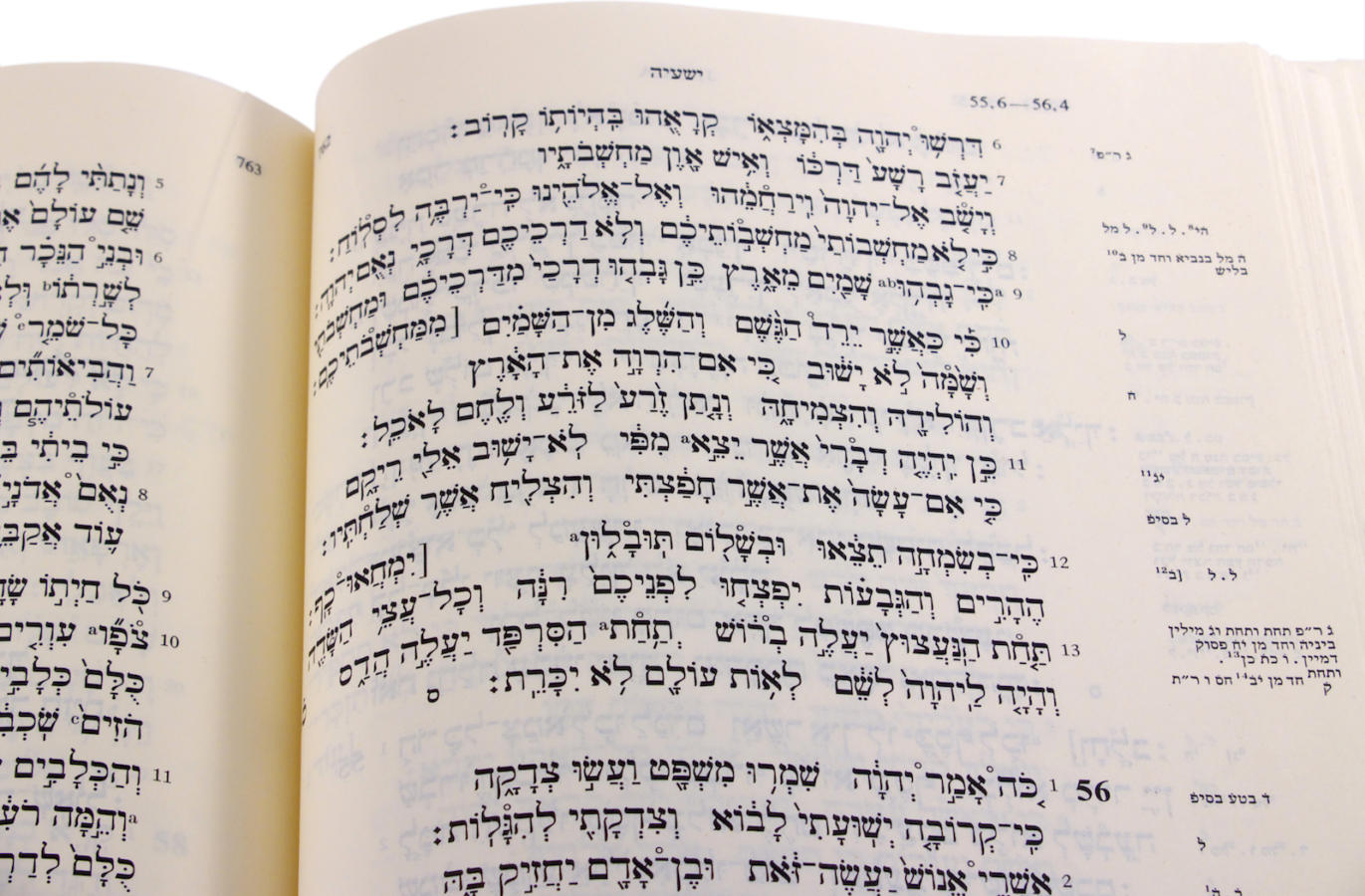

Just as the Torah is traditionally chanted, not merely recited, haftarot are sung according to the traditional notation system for biblical books, called ta’amei ha-mikra or, among Ashkenazim, trope. A haftarah, unlike a Torah reading, is chanted with a separate trope in a minor key that yields a more plaintive, nuanced melody.

The person who is to read the haftarah is called to the Torah for a last, additional aliyah called “maftir.” The term (of which “haftarah” is a noun form) is related to the verb “to depart” and stems from the fact that this aliyah is an addendum to the Torah reading. Several verses at the end of the last aliyah of that day’s Torah reading are repeated in the aliyah read by or for the maftir.

Although there is no essential link between bar/bat mitzvah and the haftarah, it has become common practice for an adolescent becoming bar/bat mitzvah to take on the task of chanting the haftarah and associated blessings. In this way, perhaps, the haftarah has emerged from the shadows, where it formed merely an addendum to the “main event” of Torah reading, into the liturgical spotlight, where it is given the full attention that, one might argue, it deserves.

aliyah

Pronounced: a-LEE-yuh for synagogue use, ah-lee-YAH for immigration to Israel, Origin: Hebrew, literally, "to go up." This can mean the honor of saying a blessing before and after the Torah reading during a worship service, or immigrating to Israel.

Haftarah

Pronounced: hahf-TOErah or hahf-TOE-ruh, Origin: Hebrew, a selection from one of the biblical books of the Prophets that is read in synagogue immediately following the Torah reading.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Sukkot

Pronounced: sue-KOTE, or SOOH-kuss (oo as in book), Origin: Hebrew, a harvest festival in which Jews eat inside temporary huts, falls in the Jewish month of Tishrei, which usually coincides with September or October.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

trope

Pronounced: TROPE, Origin: Yiddish, notations indicating the tune for chanting the Torah portion or other biblical text.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.