He heard a cow cough and that was his call to action. Nathan Straus, Jewish businessman, philanthropist and social activist was shocked when that otherwise healthy-looking animal on his farm died, so he ordered an autopsy, which revealed that the cow’s lungs were loaded with tuberculosis.

It was that moment, in 1892, when Straus became a fierce advocate for the pasteurization of milk.

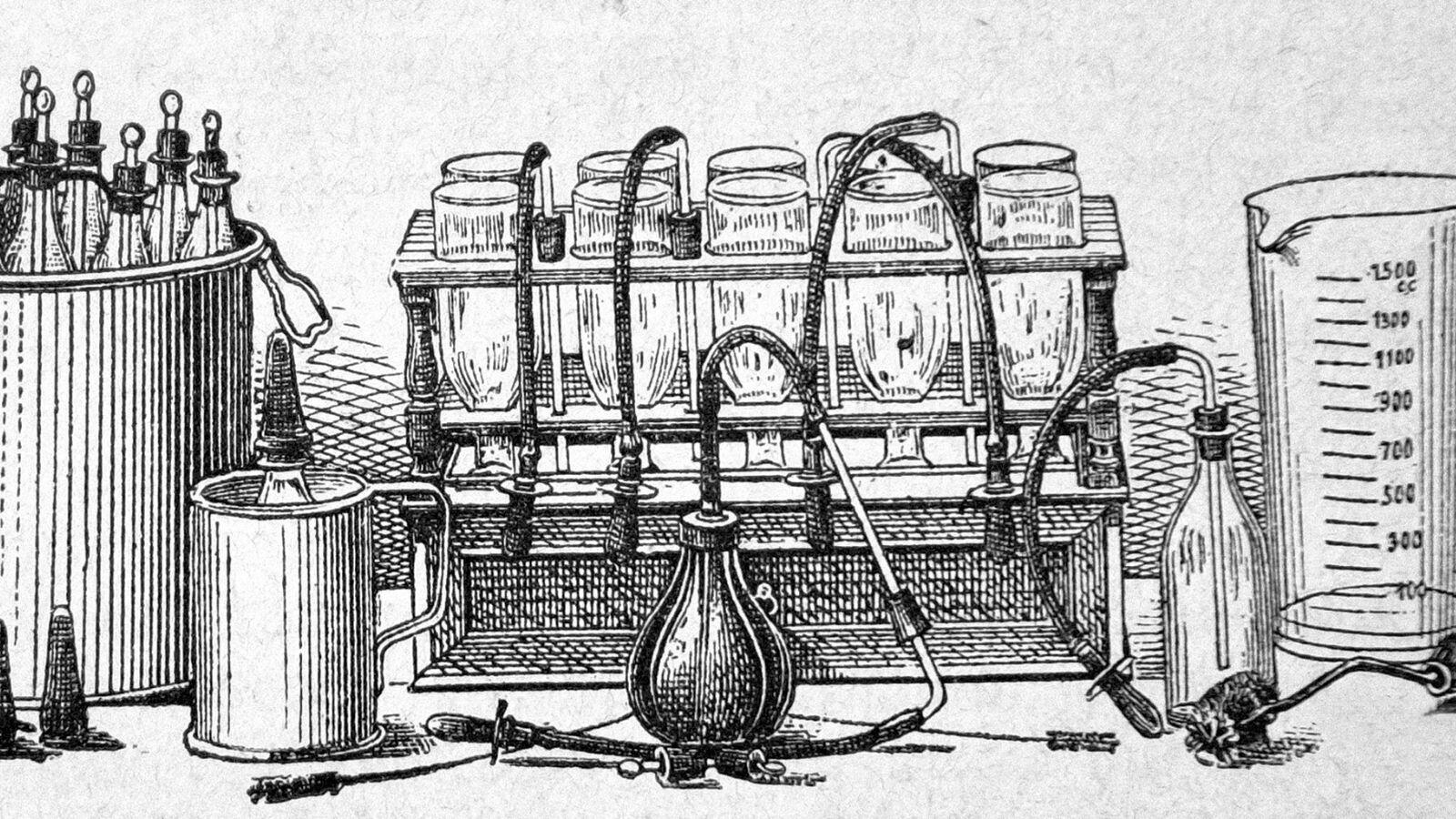

Pasteurization, the process by which milk is heated and quickly cooled to rid it of germs, had actually been discovered long before, in 1865, but had not yet become standard in the food industry. Although Straus wasn’t a scientist, he suspected that consuming milk from sick cows would transmit illness. He made sure his own children drank pasteurized milk, but his vision, to save all children from needless death, inspired him to do much more. During the 1890s, he set up “milk depots” in dozens of cities, where he gave away free pasteurized milk to poor families and donated a pasteurization plant for New York City’s orphan asylum, where over 40% of the children died every year.

The result? The death rate for children plummeted.

The Nosher celebrates the traditions and recipes that have brought Jews together for centuries. Donate today to keep The Nosher's stories and recipes accessible to all.

Unfortunately, clear scientific facts and statistics did not move the political machinery necessary to make pasteurization mandatory. Straus, who by 1898 had become president of the New York City Board of Health, was vilified by bureaucrats and politicians. Milk producers and distributors balked at the increased costs of pasteurization. Some politicians resented forcing the issue. Doctors were not yet convinced of the procedure’s efficacy. Most of the public remained ignorant of the benefits.

Straus was not a man to give up though. Even after he was arrested for “adulterating” milk (found to be untrue) he remained tireless in his advocacy and generosity. He donated pasteurization plants throughout the United States and in parts of Europe.

By 1908, the statistics were undeniable: voluntary pasteurization had dramatically reduced the infant death rate and could no longer be ignored. Chicago passed a pasteurization law (the first city to do so). It took six more years and a typhoid epidemic to convince New York City, which mandated pasteurization in 1914, followed by cities throughout the United States.

The political activism needed for legislation of this kind was nothing new to the Straus family. Nathan’s father, Lazarus Straus, left his native Bavaria in 1852 for America, where he believed his democratic views would be more acceptable (the rest of the family followed a year or so later). The Straus brothers were all active in progressive Democratic politics. In 1894 Nathan was even offered the nomination of Democratic candidate for mayor – but he declined.

The Straus family didn’t start out with much money in this country. They lived in Georgia and worked as itinerant peddlers, then opened a dry goods store. Although they made it into a successful business, they lost everything during the Civil War and decided to move to New York, where they started out selling glassware and china in the basement of R.H. Macy & Co. The business flourished. Eventually the Straus family became the owners of both Macy’s and Abraham & Straus. By then they were multimillionaires.

In his years as a department store mogul, Nathan Straus continued to think about how he could help those less fortunate. He was the first to introduce lunchrooms where employees could get a decent, but inexpensive meal. He had bathrooms installed and medical services available for his workers. Beyond his own businesses, during the financially troubled years of 1892-1894 he donated coal to the poor throughout the city and established homeless shelters. In the harsh winter of 1914, he gave one-cent meals away at his milk depots.

There is an old Jewish proverb: “What you give for the cause of charity in health is gold; what you give in sickness is silver and what you give in death is lead.” Nathan Straus lived by this saying; he gave away most of his fortune while he lived and was in good health. Beyond what he accomplished in the United States, he was active in the movement to create the Jewish state of Israel. He gave one of the first major gifts to Hadassah when it was a fledgling organization. Some historians have estimated that he gave more than half his fortune toward the development of Israel.

The city of Netanya, in Israel, is named for Nathan Straus. And there’s a small plot of land named Straus Square in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the neighborhood where several Straus milk depots once operated. The square was dedicated in Nathan’s honor shortly after his death in 1931. But the greatest, ongoing monument to this extraordinary mensch is the millions of children whose lives were and continue to be saved because of his efforts to make sure milk was pasteurized.